The master's bearded cheeks were pale as the women's as he said, "Noble ladies, we're in great danger. I doubt we'll outride this storm wi'out a miracle. Ye must pray and make vows."

Lady Scrope screamed and wrung her hands. "Which saint," she cried, "which saint will help?"

The master shook his head. "I know not. We mariners pray to the Blessed Virgin of the Sea - in the hold they pray to Saint James - mayhap your own patrons will intercede for you. But without a miracle we're doomed."

The women stared at him yet another moment, then the Princess Isabel pulled herself to her knees on her bunk crying wildly, "I vow my ruby girdle and my gold hanap to you, Saint Thomas a Becket, if you will save me, and I vow to Saint Peter that I'll make pilgrimage to Rome as well."

Katherine knelt with the rest, bracing herself between the thwart and a bolted-down chest. Through her mind like a shout ran passionate words: Don't let me die, yet, don't let me die, for I have never really lived! Quick as light she felt a fearing shame that she could have so wicked and untrue a thought at this moment when her soul was in peril, and she clasped her hands crying silently, Sweet Saint Catherine, save me! But her thoughts would not compress themselves into the vow. Candles, yes, and money, yes - but she felt that Saint Catherine would not save her just for these. For what, then? Suddenly in this moment of danger she saw into a dark corner of her heart she had kept hidden, and she made her vow.

The miracle was wrought, by which saint or all of them together there was no means of knowing, though the master gave credit to the Blessed Queen of the Sea. At any rate, just as dawn broke over the bleakly distant shore of Brittany, one of the mariners had seen a strange light in the sky and pinkish cloud beneath it shaped like a lily. This was a sign that their prayers were heard, for the wind died at once and they had drifted to the lee of the baleful little Isle d' Ouessant, where the water was calmer, and yet the outgoing tide kept them off shore while they caulked their leaks and pumped the hold dry. On shore the frustrated wreckers danced and shook their fists at the ship, but they dared not try to board because of the cannon mounted on the decks and the archers who ranged themselves along the rail.

By noon a gentle wind had sprung up from the north, the Grace a Dieu's great painted sail filled, and the ship resumed her course for Bordeaux.

Four days later, on the vigil of Our Lady's Assumption, the Grace d Dieu sailed up the broad Gironde with the afternoon tide arid veered south into the narrower Garonne while the village church bells along the banks rang for the beginning of the festival. It seemed excessively hot to the Englishwomen, who were seated on deck beneath a striped canopy. They had never seen a sun so white and glaring, or river water so turbidly yellow, and even Princess Isabel's insistent voice was stilled.

In anticipation of the landing at Bordeaux, all the ladies had dressed in their best; which entailed furs and velvets far too warm for the climate. Katherine's best was of dark Lincoln green with a sideless apricot surcote trimmed with fox. The cauls which confined her hair on either side of her face were woven of gold thread, which deepened the tone of her glossy bronze hair as they accented the golden flecks in her grey eyes. She knew that no colours suited her quite so well as the richness of dark green and gold, and she was happy in the possession of becoming clothes, but she had, as always, little consciousness of the challenging quality of her beauty.

Now at twenty the last angles of extreme youth had softened into rounded bloom, and she moved with languorous grace. Her beauty had an exotic flavour far more vivid than when Geoffrey Chaucer had first sensed it at Windsor. It was this flavour that caused Princess Isabel's angry whisper to Lady Roos, as she watched Katherine, who stood by the rail leaning her chin on her hand and gazing out at the strange white plaster houses, gilt crosses and red roofs of this new land.

"That woman's no true-born of that herald de Roet! She's some bastard he got on a Venetian strumpet - or mayhap Saracen. Look how she holds her hips!"

"To be sure," said Lady Roos, striving to please, "and her teeth are most-un-English - so small and white."

"Mouse teeth!" said the Princess, angrily pulling her lip down over her own teeth, of which several were missing." 'Tis not that I mean! But her effrontery - I shall tell my brother of Lancaster that I find her most unsuitable choice for a waiting-woman - though in fact I believe she's invented that tale as excuse to worm her way over here, that and the pretty story of a wounded husband! I've seen a great deal of the world, and I can scent a designing woman quick as smell a dead rat in a wall, I can alway - s - " The Princess's suspicions were cut short by a rushing of mariners and archers to the starboard rail amidships and a chorus of halloos, while the watch in the crow's-nest dipped the Lancaster pennant and raised it again on the mast.

The Princess heaved herself up from her chair and went to the rail. "Why, 'tis John - come to meet me!" she said complacently, peering down at the approaching eight-oared galley. Her younger brother was standing in the prow, his tawny head brilliant and unmistakable in the sunlight.

Katherine had discovered this fact some five minutes earlier when the galley first glided in sight down the river, and the sudden violent constriction in her chest stopped her breath. Her first instinct was flight - down to the cabin. She controlled herself and remained where she was. Sooner or later this moment must be met, and she armoured herself with the certainty of his indifference to her.

The galley drew alongside and the Duke ascended the ladder, followed by the Lords de la Pole and Roos. The Duke jumped lightly on to the deck and smiled at the assembled mariners and archers. Katherine, watching from above, saw Nirac dart out from the crowd of men and, kneeling, kiss his master's hand. The Duke said something she could not hear but Nirac nodded and drew back with the others. Then the Duke came up the steps to the poop deck and walking to his seated sister, kissed her briefly on both cheeks, while the other ladies curtsied. There was a further flurry of greeting when the other gentleman clambered up. De la Pole greeted his sister, Lady Scrope, and Lord Roos his wife, while Katherine still stood rooted in the angle of the rail.

The Duke turned slowly, negligently, as though without intent until he saw Katherine. Across the heads of the fluttering, chattering ladies their eyes met in a long unsmiling look. She felt him willing her to come to him, and her lids dropped, but she did not move. After a moment he covered the space between them, and she curtsied again without speaking.

"I trust the voyage was not too disagreeable a one, my Lady Swynford," he said coolly, but as she rose her eyes were on a level with his sunburned throat and there she saw a pulse beating with frantic speed.

"Not too disagreeable, Your Grace," she said and rejoiced at the calm politeness of her tone. She felt the slight hush behind them and saw the Princess' watchful stare; lifting her voice a trifle she added, "How does my husband? Have you heard, my lord?"

"Better, I believe," John answered after a moment, "though still confined to his lodgings."

Katherine again meeting his gaze saw the colour deepen beneath the tan of his cheeks. "I'm longing to see Hugh and care for him," she said. "May Nirac guide me to Hugh's lodging directly we disembark?"

A strange almost bewildered look tightened the muscles around his eyes, but before he answered a strident voice called imperiously, "John, come here! I've much to tell you - you've not heard yet the peril we were in on this wretched ship - the King's Grace, our father, has sent special message - and how long are we to be kept sweltering here in this infernal heat?"

"Ay, Nirac shall guide you, Lady Swynford," he said, then turning to his sister laughed sharply. "Your commands, my sweet Isabel, plunge me back into the happy days of my childhood. In truth, you've changed but little, fair sister."

"So I'm told," said the lady nodding. "Lord Percy said but t'other day, I looked as young as twen - , as several years ago. By Saint Thomas, what's that caterwauling?" She broke off to glare indignantly around the deck. A medley of voices had arisen from all parts of the ship. A confusion of sound at first, until led by the high clear tenor of the watch, it resolved itself into a solemn melody, a poignant chant carried by some forty male voices.

"It is the hymn of praise to the Virgin of the Sea," said John. " 'Tis sung on every ship of all nations when port is safely reached - for see, here is Bordeaux." He pointed to the white-walled town curving around its great crescent of river, and dominated by the high gilt spires of the cathedral.

Here is Bordeaux, echoed Katherine's thought, and the words blended with the great swelling chorus of the Latin hymn the men sang: "Thanks to Thee, Blessed Virgin, for protection from danger, thanks to thy all abiding mercy which has saved us from the sea - -" She shivered in the violent sunlight, staring at the garish savage colours on the river-bank: the white and scarlet houses, the purple shadows, the brilliant yellows, crimsons, greens of vegetation shimmering in heat beneath a turquoise sky, and she thought with foreboding of how far away was the cool misty Northland, and all safe accustomed things. She fastened her attention on the city in front of her so that she might not turn again to look at him who stood behind her on the deck.

CHAPTER XIV

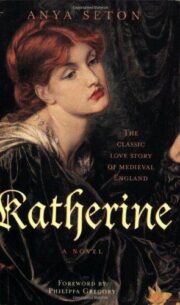

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.