"If ye're to call the parson," he said, scowling at Milburga, " 'twill mean that fat ox'll feed here after, and our fine young lady be down for once, God damn her finicking foreign ways." He picked up his sharpest knife and on the worn chopping block began to slice the old sheep's entrails for a mortrewe.

The initial good will Katherine had aroused in the manor by reason of her beauty, youth and the promptness with which she had done her duty in conceiving an heir had soon died down. After all, she was a foreigner, not only alien to Lincolnshire, but actually born in the country which they held to be their hereditary enemy. She spoke an English they had trouble in understanding. "Norman English," said Will Cooke contemptuously. And yet she was neither nobly born nor rich. She was no lady they could boast of to the serfs on nearby manors, at Torksey or Stow. And, moreover, she was a nuisance. Were it not for her, the house carls might all have returned to their village cots and own pursuits,, as they had before Sir Hugh's brief visit. Defying the nearly helpless Gibbon and the reeve, they might well have mutinied against her, even braving Hugh's displeasure later. But they were deterred by the usage of generations. Satan grinning from his hellish flames waited eagerly to pounce upon the serf who disobeyed his feudal lord, and while Katherine might be unpopular, she yet carried within her the Swynford heir to whom they would all someday do homage.

Katherine, sunk in sickliness and torpor, knew that they gave her grudging service, but had not the spirit to care. The chill dampness which crept upward from the moat seemed to have got in her bones. She shivered often and coughed; of nights her throat grew so sore that it awakened her to swallow.

On the fourth Sunday in Advent the December day was clear and bright for a change. Katherine dragged herself up and feeling a trifle better, crossed over to the church for Mass. She sat alone in the lord's high boxed pew by the chancel and leaning her heavy head against a carved oaken boss, vaguely watched the priest lurch and gabble through the service. She could not see the villagers in the choir, but she heard their responses, and heard, too, the chaffering and giggles and gossiping that went on in the nave below. The dark little church grew steamy with the peasant smell of sour sweat, leeks and manure. She tried to fix her thoughts upon the Elevation of the Host, yet all she could think of were the rolls of pink fat on the priest's neck and the quivering of oily curls around his tonsure.

It was at that moment that she felt the baby quicken, and was frightened. This tapping and fluttering in her belly seemed to her monstrous. Suddenly she thought of a tale she had heard at Sheppey of a boy who had swallowed a serpent's egg, the egg had hatched inside him and the snake, frantic to escape, gnawed -

Katherine stifled a cry and rushed from the pew through the side door of the church into the open. She sank on the coffin bench beneath the lych - gate and drew great lungfuls of the cold sparkling air. Two of Margery Brewster's children were sliding on an iced puddle beside the church path and they stopped to stare at her in wonderment. Her terror receded and she grew ashamed. She must go back in church and apologise to the Blessed Body of Jesus for her irreverence. She got slowly to her feet, then turned round in amazement, for a horse came galloping down the frozen road beneath the wych - elms.

The children turned from gaping at her and gaped at the horseman. He reined his mount before the drawbridge to the manor, and Katherine with a great leap at her heart saw that he wore on his tunic the Lancaster badge.

She ran across the court and greeted him fearingly. "Whence do you come? Is there news of the war?"

The lad was Piers Roos, the Duke's erstwhile body squire, who had been left at home to serve the Duchess. He had a fresh freckled face and a merry eye. He pulled off his brown velvet cap to disclose a mass of tow curls, and grinning at Katherine said with some uncertainty, "My Lady Swynford?"

She nodded quickly. "What news do you bring?"

"Nothing but good. At least we know no war news yet from Castile. I come from Bolingbroke, from the Duchess Blanche. She sends you greeting."

"Ah -" Katherine's drawn little face softened with pleasure. She had never dared hope that the Lady Blanche would indeed remember her; and during these months at Kettlethorpe the London and Windsor days had gradually faded into fantasy.

"She bids me escort you to Bolingbroke for the Christmas festival, if you'd like to come."

Her indrawn breath and the sudden shining of her shadowed eyes were answer enough, and Piers Roos laughed, seeing that she was even younger than he himself and not the solemn, weary woman she had seemed as he dismounted.

"We'll go tomorrow then, if you wish. The ride'll take but a day."

"I - I cannot go fast," faltered Katherine, suddenly remembering, and blushing. "I - they - think I should not ride at all."

"What folly," said Piers cheerfully, understanding at once. "The Lady Blanche is larger than you and she still rides out daily."

"The Lady Blanche!" Katherine repeated, wondering that she should be amazed, and why the young squire's information came as a small unpleasant shock. "When?"

"Oh, March or April, I believe. I know naught of midwifery." He laughed outright, and Katherine after a minute joined him.

The energy Piers' invitation brought her buoyed Katherine through all difficulties. She ordered Doucette to be curried and groomed and ignored the gloomy disapproval of her household.

The next day her sore throat had disappeared, the fluttering in her belly she did not notice; she smiled and hummed as she crossed the inner court to take leave of Gibbon.

"Ay, mistress," he said sadly, as he stared up at her from his pallet. "You're in a fever to be quit of Kettlethorpe."

"Only till the Twelfth Night," she cried. "Then I'll - I'll be back. And I'll not pine any more, I promise. I'll help you in the manor again."

"God - speed," he said and closed his eyes against the light. Hugh would not like it, and yet even Hugh would not have made Katherine refuse an invitation from the Duchess. I could not stop her from going, thought Gibbon, and sighed. Could not, since he had neither strength nor power, and would not, for she was still such a child, and he knew well how much maturity it took to withstand loneliness and boredom. He did not believe with the villeins that she was wilfully imperilling her baby, but many nameless forebodings came to him in the long night hours, and he wished as heartily as the rest of the village that Hugh had seen fit to marry the noble Darcy widow, of Torksey.

CHAPTER VIII

Bolingbroke lay clear across the county near the eastern coast of Lincolnshire. It was a small fair castle set in meadow - lands and encircled by the protecting wolds. Even in winter the meadows were green beneath their coating of hoar - frost; and the little turrets and high central keep, all beflagged in scarlet and gold, had a gay welcoming look. It was the Lancasters' favourite country castle; there Blanche had spent much of her girlhood, and there she and John had come for seclusion in the first days of their marriage.

It held for her many happy memories, and she had returned to it now, knowing that its homely shelter would help her bear the anxiety of her lord's absence, and the anxiety of awaiting the new baby. This time her prayers and pilgrimage to the Blessed Virgin of Walsingham must be answered. It would be a boy, and it would live, as the other baby boy had not.

From the moment when the Lady Blanche herself met Katherine in the Great Hall and, taking the girl's hand kissed her on the cheek, through the twelve days of Christmas, Katherine managed to forget Kettlethorpe. With the rest of the Duchess' company, Katherine immersed herself in the serene and gracious aura which surrounded Blanche.

The Duchess, thickened by pregnancy, no longer made one think of lilies, yet she was no less beautiful in her ripe golden abundance, and Katherine admired her passionately.

There were few guests, for Blanche smilingly explained that she had enough of company at the Savoy or at court and wished for quiet. The Cromwells from nearby Tattershall Castle rode over on Christmas night, and the. Abbess of Elstow, who was cousin to Blanche, spent the days between St. Stephen's and New Year's, but so intimate was the castle gathering that Katherine wondered much, while she rejoiced, that she had been invited.

She put it down to kindness of heart, and tried to repay the Duchess in every way she could. The Duchess responded with affection and growing interest in the girl. And yet it was a sentence contained in a letter she had received from her husband which had prompted the invitation.

The Duke had written soon after landing in Brittany and assembling his command of four hundred men - at - arms and six hundred archers for the march south to join his brother and the exiled Castilian king at Bordeaux. He wrote in a happy confident mood, telling his tres - chere et bien - aimee compagne many items of news: that the fair Joan, Princess of Wales, was enceinte again and near to term; that King Pedro, God restore him to his rightful throne, had with him at Bordeaux his handsome daughters, and that the desolate plight of these wronged princesses had captured the sympathy of all the English, who would certainly triumph over that baseborn fiend Trastamare, and the lilies and leopards of England would float at last above Castile and fulfil Merlin's age - old prophecy.

Descending into less exalted vein, the Duke had shown his usual consideration for Blanche's comfort, asking if the steward at Bolingbroke had repaired the bridge over the outer moat yet, and how the masons were progressing with the stone portraits of the King and Queen on the refurbished church, for "it is there, dearest lady, that our child will be christened, and I pray I may return in time."

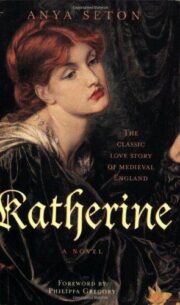

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.