Katherine's despondency reached a point where she felt that she would have welcomed goblins or any other weird visitant which might break the monotony and isolation of Kettlethorpe, when Ajax suddenly abandoned his bones, stiffened and growled.

She crossed herself, staring fearfully at the protecting hazel withes, then she heard the halloo of a human male voice and Old Toby's quavering answer, while Ajax precipitated himself against the door, barking and growling.

She spoke to the dog, held him by his collar and opened the door waiting eagerly. No visitors had come to Kettlethorpe since a wandering friar after Michaelmas. But it was only Sir Robert, who had just returned from amusing himself in Lincoln for three days.

Katherine was so disappointed that tears spilled down her cheeks, a display she knew to be revoltingly childish. "The smoke - " she said." 'Tis so smoky in here." As indeed it was.

A goblin wind had blown up and puffed all the fire smoke back into the Hall through the open roof hole.

"Ay, a wuthering night," said the priest, brushing twigs and mud off his robes. He shuddered. "I mislike Hallow E'en, there's things abroad - best not thought on. I'd not of come back today but for the Feast of All Saints tomorrow. There be some in the will want Mass said."

"I should certainly hope so - I know I do," said Katherine shortly. Father Robert's idea of his parochial duties was exceedingly flexible. Which pleased Hugh well enough.

"I was calling at the George 'n' Dragon, in the town, ye know where it is? The big tavern near the castle uphill from what folks used to call the Jewry, not in our time, nor our gaffers' time either though - "

"Yes," murmured Katherine. There was never any hurrying the priest's thick ramblings, especially when he was bursting with ale like an overripe plum. She glanced wearily at the roof over the dais, where the thatcher had not properly repaired the leak. It must have started to rain, for the usual trickle plink - plonked on the table.

"Tavernkeeper - Hambo o' Louth he's called, he knows I drop in from time to time - he told me, Hambo did, there was a pedlar come through Lincoln, three days back, on his way to Grimsby. Pedlar what carries mostly ribbons, threads, gewgaws for the women. Seems he'd started in London and bore a letter. He left it with Hambo, for when someone from here'd drop by."

"Letter!" Katherine jumped up. "Letter for Kettlethorpe! Jesu. Father, give it to me!"

The priest's fat fingers fumbled with maddening slowness at the buckle of his pouch. Finally he held out a sealed piece of parchment. "Is it sent to you?" he asked, having puzzled for some time over the looks of the inscription, and this being the first letter he had ever seen close.

"Yes, yes," she said, tearing at the seal. "Why, it's from Geoffrey!"

She read rapidly, while her mouth trembled, and her eyes darkened. "No bad news about Sir Hugh?" cried the priest.

"No," Katherine said slowly. " 'Tis not bad news. It's from a King's squire called Geoffrey Chaucer; he and my sister were married in Lammastide. They're living in London, in the Vintry, until my sister returns to service with the Queen."

Father Robert was impressed. So glib she talked about the King and Queen. He pursed his thick lips and looked at her with new respect.

"London," said Katherine, on a long sigh, gazing around the dark bare Hall, "seems very far away."

"Well and it is" said the priest, rising reluctantly, for she was staring at the letter and obviously not going to offer him anything to drink for his pains.

When he had gone, she re - read her letter, and one sentence especially. Geoffrey had written, "Philippa bids you not grow overworldly in the luxury and High Estate which you now enjoy - but I dare add I hope you amuse yourself right well, my little Sister."

Katherine smiled bitterly when she read that and put the letter at the bottom of her coffer.

More and more during the autumn months as her pregnancy advanced, lethargy came over Katherine, and she drew into herself. Her mind felt as though it grew thick as pottage, and she was continually benumbed by cold. Her initial interest in the manor waned, she scarce found the energy for talks with Gibbon any more, and he, seeing this, did not trouble her, having established a fair working relationship with the reeve.

After the leaves fell and the freezing November rains began, Katherine stayed almost entirely in her room, either shivering by the smoking fire or huddled in the great bed beneath the bearskin, trying to shut her ears to the howling wolves in the forest. Sometimes she aroused herself and plied a listless needle to make swaddling clothes for her baby. But the baby still seemed imaginary. Even though her belly and her breasts had swollen and grown hard, she had no sense of its presence within her.

"It'll be different when you quicken, lady," said Milburga. This was the servant Katherine had chosen as personal waiting - maid, because she was cleaner and less stupid than the others. But Milburga was old, being over thirty and a widow, and she treated Katherine with a blend of oily deference and petty bullying that the girl found annoying.

On St. Catherine's Day, November 25, Katherine awoke to find that she had been crying in her sleep, and knew that she had dreamed of her childhood. In the dream she had been little "Cat'rine" again, crowned with gilded laurel leaves and perched on cushions in the middle of her grandparents' kitchen table at the farm in Picardy. There were laughing faces around her, and hands stretched out towards her with gifts - straw dolls and shining stones and apples - while many voices sang, "Salut, salut la p'tite Cat'rine, on salut ton jour de fete!"

Then in the dream her big handsome father lifted her from the cushions and kissed her while she snuggled in his arms, and he pressed a little gingerbread figure of St. Catherine into her mouth. She tasted the heavenly sweetness of it until someone wrenched her jaws apart and snatched the sweetmeat away. And she awoke weeping.

There had been light snow in the night, the wind had blown a fine drift through the loosened shutter and there was a ridge of white along the bare stone floor beneath the iron perch where her cloak hung.

The fire had died to ashes. Katherine looked at the cold grey ashes and her tears changed to a loud and passionate sobbing. When Milburga bustled in from the outside stairs with the morning ale, die maid exclaimed, "Mistress, what ails ye?"

As the girl merely hid her face in her arms and continued to sob, the woman drew back the covers and made a quick examination.

"Have you pains, here or here?" she demanded. Katherine shook her head. "Leave me be. Go away," and she sobbed more violently.

Milburga's sallow face tightened. "Stop that rampaging at once, lady! Ye'll harm the child."

"Oh, a murrain on the child!" cried Katherine wildly, rearing herself on the bed.

"Saint Mary protect us!" gasped Milburga, backing away. Her pale mouth and pale eyes were round with horror. She receded to the door and stood gaping at her mistress.

The wild angry grief fell off Katherine like a mantle, leaving her afraid. "I didn't mean it - " She put her hands on her belly, as if to reassure the dark outraged little entity inside. "Send for Sir Robert. Tell him he must celebrate a Mass - this is my saint's day - my sixteenth - that's why - why - "

But of what use to explain to that tight shocked face that she had been sobbing for her own childhood, for the dear lost days of special cherishing and festival. Even at Sheppey, where she had been the only Katherine, the nuns had made a little atmosphere of fete and congratulation for her on this saint's day. Here there was nobody to either cherish her or care.

Milburga, bound on her errand to the rectory, paused in the kitchen below to regale the other servants with their mistress' shocking behaviour. They clustered around exclaiming, the cook, and the servitor and the dairymaid. All work stopped at once, except that little Cob o' Fenton, the towheaded spit - boy, crouched in his niche in the great fireplace, automatically turning the handle with his toes while he longed to be out in the raw misty air fishing in the Trent. They were roasting a lean old ewe, and her scanty grease smelt rancid as it hissed into the fire. In truth the manor food was poor, and slackly prepared, for there was no one at the High Table now that Lady Katherine kept to her room so much and was growing as strange and solitary as the Lady Nichola.

" 'Tis the curse, no doubt, creeping on them both," said Milburga, shaking her head with gloomy relish. "Soon we'll hear the pooka hound a-baying in the marshes."

"Jesus save us!" squealed Betsy, the dairymaid, her child - mouth quivering. They all crossed themselves.

"Nay," said the cook sourly, shaking his knobby grey head. "I believe 'tis no Swynford curse, though well they deserve it. The demon hound was sent by the devil to haunt the de la Croys for their grievous sins. That's why they sold us and the manor to Swynfords." He eased his rheumatic joints on to a bench.

The others listened respectfully. Will Cooke was over fifty and well remembered the old days under the de la Croys. He and his fathers before him had always been manor cooks, yet he had no liking for the lords or his work.

During the years of Hugh's absence he had moved into his daughter - in - law's cot in the vill and taken happily to wood - carving.

He had been the most defiant of the serfs when at the manor court Hugh had ordered him back to his hereditary duties, and had flogged him so hard that his shoulders oozed blood for days. Will would have run off to hide in Sherwood forest, had he been younger, but his stiffened knees hampered him, as did the dead weight of custom. Kettlethorpe lords had always been so. Sir Hugh was no worse than the de la Croys who had thrown his father into the tower dungeon for the inadvertent scorching of a spiced capon.

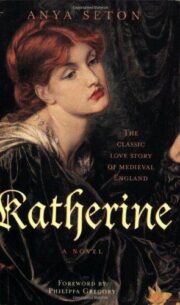

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.