Hugh made an exclamation, loosing the skinny shoulders, grabbed Toby's lantern and threw open the unbolted door to the Great Hall. Inside it was as dark and dank as out. There was no fire, nor sign of any, on the central hearth. The eating trestles, planks and benches were stacked high on the far wall. Rain splashed through a hole in the thatched roof on to a corner of the lord's dais.

"Ellis!" Hugh cried. "Gallop to the village and bring me back serfs. By God's nails, we must have food and warmth, no matter what's amiss here!"

The squire ran out and mounted his horse. Hugh put the lantern on the hard-packed earthen floor. He turned his face slowly from one end of the Hall to the other, remembering it in the days of his boyhood, when there had been torch and firelight, the smell of roasted meat, and ten servants running to attend the Swynford appetites.

Katherine crumpled down in one of the window embrasures, leaning her head against the stones, so cold and weary that she could not think. Her teeth chattered, and beneath her dropped lids the flickering shadows in the Hall swayed like water.

Then through her exhaustion she heard a rustling at the door, and opened her eyes. A woman stood there staring at Hugh. She was small and thin as a stick, her black gown flapped around her in the wind from the re-opened door, and her triangular widow's coif was no whiter than her narrow face.

"Is it you - Hugh? Have you come?" She spoke in a high sighing voice in which there was no surprise, or pleasure or dismay. "I thought you'd come. They told me so."

Hugh had jumped back as she appeared suddenly gliding into the hall. The contempt he had always felt for his stepmother and the anger at the havoc she had obviously wrought on his manor were both checked by the unfocused stare of her red-rimmed dark eyes.

"Ay lady," he said warily after a moment, not moving towards her. "I've come home with my bride." He pointed to Katherine, who slid slowly from the window and made a curtsy. "And I mislike the welcome you give to the new lady of Kettlethorpe."

The woman turned her mournful gaze on Katherine. "A bride?" she said, shaking her head in disbelief. "A bride at Kettlethorpe? They did not tell me that."

"Who did not tell you, madam?" Hugh snapped.

The Lady Nichola Swynford waved a bony hand vaguely towards the east. "The folk who live in the water, in the river, in the well. One mustn't say their name. They tell me many things."

"God's wounds," Hugh whispered, crossing himself and stepping close to Katherine. "She's lost the few wits she had."

The girl nodded and sat down again in the window niche. She looked at her husband, mud-spattered, his habitual scowl modified by the uneasy glances he threw his stepmother. He stood near the lantern, legs wide apart, his bandaged hand resting on his sword hilt. They both watched the Lady Nichola, who began to drift restlessly around the Hall. As the black-robed figure came to the water that streamed through the roof on to the dais, she stopped. She cupped her hands and caught some of the water, murmuring soft words to it as though in greeting.

Katherine shut her eyes again. A merciful blankness fell across her mind.

During the next days at Kettlethorpe, Katherine had opportunity for the exercise of many qualities she had not known she possessed. Her strong young body recovered soon from the drenching and exhaustion of her arrival; the recovery of her spirits and the acceptance of conditions so different from her imaginings took longer. Yet a sturdy common sense came to her aid. For better or worse this was now her home, and she the lady of the manor. She was child enough to feel pride in the sudden responsibilities thrust upon her. It was a little like the games of being grown-up ladies she had played with other girls at Sheppey, yet this feeling of play-acting did not preclude a hard-headed realism. She thought often of Philippa in those first days and wondered how her sister's orderly methods would have righted this muddle.

Kettlethorpe parish stood in the isolated corner of Lincolnshire at the south-west tip of Lindsey. It was bounded by the River Trent on the west, Nottinghamshire on the south and the angled Fossdyke on the east and north - a parcel of some three thousand acres including, besides the manor village, two hamlets called Fenton and Laughterton. It had formed part of the Saxon Wapentake, or Hundred, of Well, and owed feudal dues to the Bishop of Lincoln, under whom the Swynfords held this manorial right.

It had never been a populous or especially productive manor, the soil being suited only to the growth of hay, flax, hemp and such-like, and most of the land being in virgin forest for the pleasure of its lords. Earlier owners, such as the de la Croys, had had large holdings elsewhere to supplement their rents, as indeed so had Hugh's father until mismanagement had dwindled off Nichola's dowry, leaving the Swynfords only Coleby and Kettlethorpe.

Yet these two would have supported them all in sufficient comfort, were they well administered, Katherine thought. Hugh still had over sixty serfs at Kettlethorpe, man, woman and child; plenty to give him week-work on his home farms, boon-work at the harvests and inside work to run the manor.

The trouble here, of course, was twofold; the Lady Nichola's eccentricities and the mortal sickness which had attacked Gibbon, the bailiff.

Three days after Katherine's arrival she felt well again and decided to see this man who lay in a wattle-and-daub hut at the end of the courtyard between the dovecote and the bakehouse.

The weather had at last cleared and Hugh, having bullied and whipped some sulky serfs from their own fieldwork and back into the manor kitchen, had taken Ellis and ridden off into the forest to hunt for sorely needed food. He was not sorry to put off the countless tasks which awaited him. A manor court must be called, the serfs brought to punishment, their overdue fines collected, a new bailiff found. But above all the larders must be replenished; they were completely empty. Lady Nichola lived, on sheep's milk and stewed herbs which she cooked herself in an iron pot in the tower-room where she spent all her time when she was not wandering through the marshes and fields towards the river. Gibbon existed on the fitful donations of Margery Brewster, the village alewife, who felt kindly towards him, having several times shared his bed in the days of his strength, but whose tavern duties and brood of babies left her little time for charity.

Katherine had not asked Hugh's permission to visit the bailiff. Already she had learned that the mention of painful subjects induced in him an angry stubbornness which might well have led to refusal.

She waited until she saw the tip of his longbow disappear into the forest on the other side of the moat, then set herself to a leisured inspection of her domain, much irked that she still had no proper clothes except the travel-stained green gown the Duchess had given her, not even a linen coif to hide her hair and show her housewifely status. No matter, she thought, braiding and looping the great ruddy ropes neatly on either side of her face. She was determined not to be discouraged, and to meet this new life with calmness. Since there was no one to help her, she must depend on herself, and again, as it had on the morning after her marriage, this thought gave her strength.

She decided to visit the Lady Nichola first in the tower-room. She had not seen her mother-in-law since the night of arrival, but smoke and steam sometimes drifted through the arrow-slit windows and twice she had heard a not uncheerful crooning sound from up there.

The low defensive tower had been built, as had the manor, a hundred and fifty years ago, in the reign of King John. It was attached to the hall and solar, but there was no communication with these except by the outside staircase, which also served the solar. The manor plan was simple and old-fashioned. There was the thatched two-storied Hall, forty feet long, and the narrow solar where Katherine slept with Hugh was tacked high on to its western end. Beneath the solar lay an undercroft for stores. At the eastern end of the Hall there was a kitchen, and a half-loft above it where the servants slept. These and the tower with its ancient donjon and two round rooms above were all there was to Kettlethorpe. No private chapel, no spare chambers, garderobes or latrines.

The demands of nature were answered in an open corner of the courtyard behind the dovecote.

It was a more primitive dwelling than any Katherine had ever known; even the convent at Sheppey and her grandparents' great farmhouse had been more luxurious, while the Pessoner house in London, and of course the great castle at Windsor, had shown her entirely different standards of comfort.

And the furnishings at Kettlethorpe she deemed shockingly plain and scanty for a knight's home. The planks and trestles and benches in the Hall were barren of carving and as roughly hewn as those in a rustic's cot, while the solar was furnished only with a square box frame heaped with a mouldering goose-feather bed and a flea-infested bearskin for a coverlet. It surprised her much that they should drink the small ale Hugh had commandeered from the village out of coarse wooden mazers and that there should be no object of the slightest value to be seen, not even a saint's statue, or a tapestry to keep out the constant draughts. She longed for explanation of this singular poverty, but did not dare ask Hugh, seeing that he felt shame at the condition of his estate and tried to hide it by loud rantings against his stepmother. All the more she could not ask him because she had brought him no dowry, nor had he reproached her with its lack. In justice, she owed him all her help to straighten out his affairs.

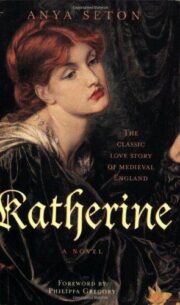

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.