John was silenced. The girl's poise showed almost aristocratic breeding, though she came of yeoman stock. And it was true that she could not run down to the leech's tent amongst all the disrobing men and find out for herself. He beckoned to one of his hovering squires, but the young man already had the required information, having just come from the pavilions.

He said that Roger de Cheyne, though faint from loss of blood, would recover, the stars being propitious. The King's leech, Master John Bray, had poulticed the neck wound. Sir Hugh Swynford was uninjured except for a twisted wrist and a bone or two broken in his hand, as a result of the Duke's blow. He had refused the services of the surgeon and gone at once to his tent.

John and all those near enough to hear the squire listened attentively and nodded approval. A gratifying tournament, few casualties and probably no deaths. At least today. Everyone knew that injuries bred fever and putrefaction later, but the outcome would depend on a man's strength, the skill of the physician and his ability to read the astrological aspects aright.

"Farewell, my sweet lady," said the Duke to his Blanche. "I'll see you at the banquet." Ignoring Katherine and the rest of the Duchess's entourage, he trotted his horse off towards the pavilions. It was necessary to punish Hugh in some way for flagrant transgression of the rules, but the heat of John's anger had passed. Poor Swynford was bewitched and doubtless couldn't help his behaviour. Besides, a fierce and vengeful fighter was invaluable in war, however improper at a tourney.

And war was now John's great preoccupation. War with Castile. A deed of arms so chivalrous as to reduce these little jousts and melees to the pale counterfeits they were.

That very morning four knights, Lord Delaware, Sir Neil Loring and the two de Pommiers had arrived at Windsor from Bordeaux bearing official letters from Edward the Prince. There had been no time for the King to digest these letters yet, but John had read them. They contained an impassioned plea from his brother, asking for help in righting a great wrong. All of England must help, all of Christendom should help, in restoring King Pedro to his throne and driving out the odious usurping bastard, Henry Trastamare. King Pedro and his young daughters had been reduced to ignominious flight, and had to throw themselves on Edward's mercy at Bordeaux and beg for help, reminding him most pitifully of England's long-time alliance with Castile. That rightful anointed kings should find themselves in such desperate plight must move every royal heart to valorous response and to arms! That was the gist of the Prince's letters, and certainly John's own heart had responded at once.

He burned to distinguish himself in battle as his elder brothers did. His military role, so far had been unimpressive, through no fault of his own, but he chafed under the memories.

At fifteen he had gone to France with his father, full of hope that he might find glory in another Crecy as his brother Edward had done nine years before. But this French campaign bogged down into a welter of plots and counter-plots. King Jean of France blockaded himself behind the walls of Amiens and would not fight; it was all anticlimax and disappointment. King Edward knighted young John anyway, but there was no glorious deed of arms to give the ceremony savour, and the King, moreover, was preoccupied with trouble in Scotland.

The English returned home in a hurry, prepared to subdue the impudent Scots who had, as usual, seized any opportunity to capture Berwick. John was jubilant again. The Scots would do as well as the French as a means to prove his courage and new knighthood. Again he was disappointed. Berwick, unprepared for a siege, gave up at once, and then the infamous Scottish king, Baliol, surrendered his country to King Edward for two thousand pounds, and the English marched unchecked to Edinburgh, burning and looting as they went.

There was nothing in this moment of Scotland's abasement to thrill a boyish heart, fed on the legends of King Arthur's days, and fretting to prove himself the perfect knight. But in Edinburgh he at least had a glimpse of chivalry. His father, the King, had intended to burn Edinburgh as a final and conclusive punishment for the Scots. But the lovely Countess of Douglas flung herself weeping before the angry conquerors, imploring him to spare the city.

And the King had listened, had raised the sobbing beauty and kissed her on the forehead in token of gallant submission. Young John himself had been one of those sent to check the soldiers and their flaming torches. That day he had conceived affection for the city they had spared, and surprised admiration for the Scots, whom he had previously thought to be uncouth monsters.

He had been sorry to leave Scotland and deeply chagrined later that year that his father had not allowed him to return to France and join the Prince of Wales. For by Michaelmas they heard the stupendous news in London. The Prince and his remarkable general, Sir John Chandos, had not only won a brilliant victory at Poitiers, but they had captured the French King!

Young John rejoiced with all England. He took his part in the triumphant pageants and tourneys that greeted the return of the young conqueror and his royal prize, but he had had to fight envy. Edward was a brilliant hero, Edward was heir to the throne, the court adored him, the people quite properly doted on him, but what was there left for a third son who felt himself potentially as great a warrior?

Lionel didn't care. He liked sports and wenching and drinking. He amiably tried to fill any role his father told him to, and beyond that he had no ambitions. But John cared very much and spent many bitter hours. His rebellion was entirely inward and soon subdued by his strong sense of loyalty, both personal and dynastic. Gradually his seventeen-year-old energy, that winter of 1357, baulked of glory, flowed in other channels. He developed an interest in art, music and reading, where his taste ran to the romantic and stirring tales of olden time.

He also discovered passion. He became infatuated with one of his mother's waiting-maids, Marie St. Hilaire, a handsome, good-natured woman in her mid-twenties who initiated him into the forthright pleasures of sex. This affair lasted over a year, when she became pregnant. The Queen, who demanded a high moral tone from her ladies, was disgusted and angry with her son too. The King, however, and John's older brothers, were amused. His father remarked jovially that at least the boy was a truly virile Plantagenet, and this episode turned the King's mind to finding John a suitable wife.

Marie was well provided for and bore her baby without fuss in London. It was a girl, and she named it Blanche in honour of the bride the King had picked out for the baby's father.

By this time John was nearly nineteen and had quite outgrown Marie. It was easy for him to fall in love with the beautiful Blanche of Lancaster. He saw her first in her father's rose garden at the Savoy Palace, and in her white-robes with her silver-gilt hair unbound as she played a Provencal melody on her lute, she epitomised for him all the Elaines, Gueneveres, Melusines of who he had read.

His marriage brought him luck and a great measure of the power he wanted, yet now at twenty-six he had still not found the opportunity to achieve glory on his own.

Castile would do that. The very sound of "Castile" was like the martial clash of cymbals, and he repeated the seductive word to himself while he rode towards the pavilions after the tournament. His heart beat faster as he saw how he would answer his brother's need at the head of an avenging host, in a latter-day crusade to fight for justice and the divine right of Kings.

He would issue the call to arms throughout his vast domains. He could raise an army of his own retainers almost overnight, and finance the expedition from his own pocket. This was to be the Duke of Lancaster.

John's musing eyes grew brilliant and he flicked Palamon to a faster pace.

As he neared the pavilions a child darted out from behind one of the tents and waved her dirty little claws. "Great Duke," she whined, "gi' alms, gi' alms - we've naught to eat."

Her slanting dark eyes peered up at him through a tangle of dusty black hair, lice crawled on the filthy rags that barely hid her skinny little body. The stallion moved away from her under the pressure of John's knees as he said, "There's food for all down by the river - bread, ale and roast oxen." He pointed to the crowd of feasting peasants.

She shook her head with a sly smile. "We darena, noble lord, we'm outlaws - me da's skulking in tha' forest."

John shrugged and gestured to Piers Roos, his young body squire who rode behind him with others of the Duke's men. Piers opened the purse at his waist and flung the girl two silver pennies. She caught them in mid-air and darted off like an otter to disappear in the bushes.

"I suppose the woods are full of runaway churls today," remarked Piers laughing to his companions. "Come as near as they dare to the feasting. And as for that ugly maid, she's a veritable changeling."

John was not listening, and yet the last word uttered by Piers' clear young voice penetrated his mind with an effect of shock. Changeling. What was there in that word to stir up turmoil? His heart of a sudden pounded heavily and his stomach heaved as though with fear. Grey eyes, grey woman's eyes seemed to stare at him from the sky - troubled, far-seeing eyes like the de Roet girl's. No - eyes like Isolda Neumann's.

He turned in his saddle and spoke sharply to the young men behind him. "Go to your tents, all of you, and leave me alone. I wish to ride in the forest."

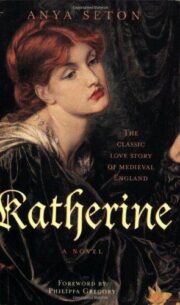

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.