"Ah sweeting," cried Hawise, her broad freckled face crinkling, "ye know I don't mean it. God's belly, there's not an hour in the day I don't gi' thanks for the marvellous thing what's happened to ye - when I think o' the black past - well, let be - we won't think of it."

They looked at each other, while the memory of all the years they had shared together hovered between them, then spoke of trifling matters while they proceeded with Katherine's elaborate toilet. John wished her to be always richly dressed, and to wear the new jewels he had given her. He took great pride in her mature beauty and liked her to enhance it by the artful application of unguents, rouges and perfumes.

After Hawise had adjusted a light seed-pearl coronet over a veil of rosy gauze, Katherine glanced into the bedchamber and said, "My dear lord sleeps late, I'm afraid I should wake him. He must sign those letters to the King before the Comte de St. Pol starts back for Windsor."

"Let His Grace rest, poor soul, he seemed mortal weary yestere'en." Hawise had indulgence now towards the Duke and did not even mind his teasing her for her jealous wardship of her mistress.

Katherine nodded, walked rapidly through the passages of the Sainteowe Tower into the beautiful Great Hall which John had now completed. It was crowded with retainers, lords, knights, squires and their ladies, all waiting for her to come so that they might sit down to eat. As she entered, the men bowed, and the ladies curtsied. The chamberlain ushered her unctuously to the dais, where her own squire, kneeling, presented her with a damask napkin.

"Good morning Roger," she said smiling at him, while the company seated themselves. "You look very merry, you won at dicing last night?"

The lad blushed, and bit his lips to keep from laughing. "Dame Fortune favoured me, Your Grace," he admitted.

He's like his grandfather, she thought - Roger de Cheyne with the bold wooing eyes, the pretty chestnut curls - -my first love, I suppose, or I thought so - Jesu, how long ago. Thirty years. She thought of the tournament, the knight with the nodding iris stuck in his helm - poor Roger who was killed so shortly after that at Najera. Blessed Mother, how many were dead that had witnessed Saint George's tournament at Windsor? She crossed herself, and turned abruptly to the French nobleman on her right, the Comte de St. Pol, "Vous vous amusez bien ici en Angleterre, monsieur, ca vous plait?" She embarked on the courteous chit-chat which was constantly required of her now.

"Parfaitement, madame la duchesse," replied the count, delicately wiping his long black moustaches, and thinking that despite the scandal of this marriage, the new Duchess had far better manners than most of the English barbarians and the further advantage of speaking pure French - which he would report to his own King Charles in good time.

The stately breakfast proceeded. Katherine longed to go out to her pleasaunce where the peaches were ripening and the new Persian lilies were in bloom, but she allowed herself no impatience. It would be hours before she could enjoy the garden. There must first be interviews with the chamberlain and the steward. She must arbitrate a quarrel between the village and castle laundresses, she must dictate answers to a dozen letters, and as most of them were begging letters, there would be conference first with the clerk of her wardrobe.

When she rose at length, a page came up to say that two nuns had just arrived at the castle and craved an audience. "Certainly," said Katherine, wondering which convent it was this time that required a benefice. "Tell them I'll receive them presently." And hoped that whatever it was they wanted, she could manage to gratify them herself from her privy purse without bothering John.

By the time she had finished her necessary morning routine, it had grown very warm, and she sent a page to the nuns to convey them to the oriel of the Great Hall,, where a faint breeze blew through the opened window. John was up at last and had gone to the chancery office with St. Pol. Except for her own women who were embroidering and spinning by one of the empty fireplaces, the Hall was deserted for the present.

Katherine seated herself in a carved gilt chair and surveyed the-two nuns with polite indifference as they bowed before her. White nuns, Cistercians, shrouded in snowy wimples and habits, a tall one and a short one. The former turned away at once and seemed to be examining the embroidered Venetian wall hanging. Katherine had had only a glimpse of a pale unsmiling profile.

The short nun began to talk in a weak insistent voice, her heavy-jawed, middle-aged face twitched with nervous little smiles. "Most kind of you, Your Grace - forgive this intrusion, really I hardly know how to explain it. Oh, I'm the prioress of Pinley - a very small foundation, you know where we are? Only a few miles from here, near Warwick - but of course we're not on Lancastrian land. Your Grace wouldn't know us - -"

What is all this about, Katherine thought, faintly amused. "Is there some help I can give you, my lady prioress?" she said, glancing in some perplexity at the rigid white back of the other nun, whose marked withdrawal was surely peculiar.

"Well," said the prioress, chewing her lips, "I don't rightly know. It's Dame Ursula there who would come. She's my sacrist and librarian, not that we have many books, I think it's maybe that she wanted, wondered if - but Dame Ursula, she talks so little, sometimes we think she's very odd, though not the way she used to be - -"

Katherine raised her eyebrows and drew them together.

"Oh," said the prioress, "she's quite deaf, I doubt she can hear me."

But it seemed that the other nun had heard. With a slow almost languorous motion she turned and looked full at Katherine, whose heart began to pound before her mind knew any reason for it, who gazed blankly at the triangular wedge of face enclosed by the white wimple, then at the slate-grey eyes that looked at her with hesitant enigmatic question.

"You do not know me?" said the tall nun quietly in the flat toneless voice of the deafened.

Katherine stared again. She pushed herself up from the chair, gripping the armrests. She tried to speak, but the blood drained from her head, she fell back sideways - and slipped off the chair.

The blankness lasted only a few moments, though it was long enough for the page on hearing the prioress' frightened cry to have summoned Catherine's women. When she opened her eyes, she had been laid on the rug, Griselda Moorehead was sponging her forehead with wine, Hawise was burning a feather beneath her nose and there was a chorus of female speculation: "What happened? The Duchess swooned - but she never does - what can be amiss?"

The prioress had drawn back and was wringing her hands, crying that it was not fault of hers, that she didn't know what happened, that Dame Ursula - -

Katherine pushed Hawise and Griselda aside, she struggled to her elbow and saw that the tall white nun knelt by her feet, the wimpled head was bowed and there were tears on the pale cheeks.

"Go away please, everybody," said Katherine in a shaking voice, "all but Dame Ursula. I'm sorry I was so foolish. The heat, perhaps - -" The women reluctantly obeyed her. Hawise made after them after she had helped her mistress to her feet and shot a long startled unbelieving look at Dame Ursula, who continued to kneel with her head bowed.

When they were alone, Katherine bent down, took the clasped thin trembling hands in hers. "Blanchette," she whispered. "Oh, my darling - I always knew - Dear God, I knew you'd come back - -"

The nun raised her head at last. "I had to see you again," she said through stiff pale lips, "I could no longer live with my hatred."

There were only two people in the castle who understood why the Duchess was closeted in her bower all that day with the Cistercian nun. These were the Duke and Hawise, who saw to it that she was not disturbed, while the mystified prioress was made welcome in the Hall.

The mother and daughter could not speak much for a long time. They wept together quietly and after a while they prayed on Katherine's prie-dieu. It was only bit by bit that Katherine comprehended her daughter's story. Blanchette was unaccustomed to talking, and her deafness, result of the scarlet fever, had increased her withdrawal into an interior world which satisfied her.

She made this clear: the convent life contented her, she wished for no other, there was no doubt that she had a true vocation. She was grateful to the nuns, who had sheltered the wild half-demented child who had come to them fifteen years ago, and who had accepted her as a novice later, though she had no dowry and pretended that she did not know her name. "I never told anything about myself," said Blanchette. "I couldn't. My soul was eaten up with fear, fear and hate.

Mother," she took a sharp breath and looked deep into Katherine's eyes, "did I hear wrong that day in the Avalon Chamber?"

It was as Katherine had suspected all these years, the added pain that had lain at the core of her anguished bereavement. Blanchette had misinterpreted the Grey Friar's accusation and had believed that her mother had deliberately poisoned her father.

Speaking distinctly, her lips slowly forming each word, Katherine effaced this horror for Blanchette at last. And the grave twenty-nine-year-old nun received the truth and understood, as the frightened child could never have.

It was the news of the marriage which had stirred Blanchette from her long self-containment. She had begun to remember her mother's love for her, to see Katherine as a woman who could never commit the hideous crime that the child had believed in. "And - I thought, I felt, that you could not have married the Duke if it were true."

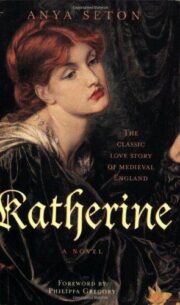

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.