"Ah," cried Richard, his eyes lighting, "those whoreson serfs. I soon dealt with them, didn't I? Well, did Our Lady send you Blanchette?"

"No," said Katherine slowly. "I've never heard what happened to her."

"And there's pain still, after all these years?" asked Richard curiously.

"Time never entirely heals the loss of a child, Your Grace," said Katherine incautiously. The King's round pink and white face hardened. The Plantagenet glint flashed in his pale blue eyes.

Richard's failure to produce an heir, and the choice of his new Queen, whose age made it impossible that she could even be bedded for years, was the common whisper of England. Anything that Richard might construe as the obliquest reference to his peculiarities was unwise.

He paid her back at once by smiling his small purse-lipped smile and saying, "Alas, I have as yet no way of knowing these parental sensibilities, have I, my lady? Young Mortimer is still my heir. 'Tis pity indeed," he said softly, watching her closely, "that your new husband's good and prolific Henry of Bolingbroke may not succeed."

Blessed Mother, thought Katherine. The sudden claws, the threat that jumped out when all was most charming. She cast about for politic answers and instinctively rejected them for frankness.

"Henry has never coveted the throne, Your Grace, any more than has my dear lord his father, and this you know right well by long years of proof."

Richard stared at her, astonished by positive rebuttal. Of late, and barely recognised, for he was fond of his Uncle John, there had been growing in Richard a dislike of Henry: so solid and masculine a man, so excellent a soldier and jouster - and so popular with the people. "I've never doubted my Uncle of Lancaster's loyalty, no matter what they said," he murmured half to himself, looking beyond her to the Duke.

"Nor need you doubt his son's, Your Grace." Katherine smiled, still a lovely warm smile, with white teeth and a hint of her youthful dimple. In both the smile and her sincere voice, there was for Richard something maternal and reassuring.

She was nearly of the age at which he best remembered his mother, the Princess Joan, and that memory brought ease.

With one of his characteristic volte-faces, Richard laughed and patted Katherine's hand. "I shall believe you, my fair new aunt," he said mischievously. "At least for tonight! God's blood, but the minstrels play badly. This banquet bores me." He stood up, shoving his plate away. like released bowstrings, the two hundred diners jumped to their feet and waited. The Cheshire guard sprang to attention.

Richard airily waved the Flemish lace handkerchief he always carried. "Clear the Hall. There shall be dancing now!"

The half-eaten food was whisked away. The subtleties not yet presented were returned to the kitchens.

Richard looked up at Katherine, who topped him by some inches, crying loudly, "My first dance of course will be with the Duchess of Lancaster." He winked at the Duke, as Eleanor gave an unmistakable anguished choke.

On the day after the banquet, the Lancasters travelled back to Kenilworth to enjoy a few days of privacy before leaving for Calais and the state meeting there with the Dukes of Berry and Burgundy - more preliminaries to peace with France.

As the ducal retinue cantered along the side of the mere towards Kenilworth, Katherine looked ahead at the red sandstone battlements with fervent relief. This was the castle which in the old days had always been home to her, its warm ruddy fabric was interwoven with memories of her children's babyhood, and of the more peaceful stretches of her love.

The watch had seen them. The trumpets blew a salute, and the Lancaster pennant ran hastily up on the Mortimer Tower. The Duke's retinue pulled their horses down to a walk, and Katherine presently said to John, "Oh my dear lord - how delicious it will be to rest here a few days."

He placed his hand on the jewelled pommel to turn and smile at her. "Your new duties are exacting, lovedy! And I fear it won't be all rest now. There's Saint Pol to be entertained. The tenants have planned celebrations for you, and all the chancery officials are here, since we have much business to discuss before going abroad."

"Oh well - I know - but that's all simple compared to court life. Sainte Marie, but these last few days at Windsor were gruelling. 'Be gracious to the Sieur de Vertain, but remember that he's outranked by Saint Pol Remember that Lady Arundel will repeat everything I say to Gloucester, and Lady Salisbury to her husband, who will tell the King, and above all be careful what you say to the King.' I never knew how hard it was to be a great lady - -"

"You do it superbly, Katrine," said John with sudden seriousness. "I've been very proud of you and of the way you ignore malice and slander."

She blushed and said quietly, "Malice and slander are accustomed things to both of us, darling. One learns to live without their hurting overmuch."

"Ay," he said, "they never disturbed me but once - that foolish changeling story. Ah, Katrine - never during the long time of our separation did I quite forget what your love did for me then."

They both fell silent as they rode through the two gates and under the raised portcullises of Mortimer's Tower into the base court, where they were greeted by the usual confusion of scurrying stable-boys, barking dogs and children. It was a different set of children now who ran in great excitement down from the inner court, escaping from nurses and governesses to precipitate themselves perilously near the rearing, snorting horses. These were John's grandchildren, Henry's brood, who summered at Kenilworth. Little Henry of Monmouth, nine years old, did not wait for the Duke to dismount, but swarmed up the flank of his grandfather's great charger, and sure of indulgence, wedged himself between the pommel and the Duke crying, "Grandsir, Grandsir, did you bring me the peregrine you promised? Did you, my lord?"

John smiled at Katherine over the child's head. "Here's a naughty mannerless lad, who thinks of nothing but falconry! Get down', you little savage, get down, you'll find out in good time." He scooped the boy out of the saddle and deposited him on the flags. "Now stand back and show the Duchess and me proper courtesy."

"Ah, but not too much ceremony, my lord," said Katherine laughing, as the boy, who had no awe of his grandfather, made a pert face. "It's good to have a pack of rowdy children around again!"

She glanced up at the weather-vane on the stable roof remembering the day Elizabeth had clung to it - Elizabeth, now at last married none too happily to the John Holland of her earliest passion, the King's lustful unprincipled half-brother. Katherine walked through the arch after the Duke and saw the stone bench by the keep where Philippa had said gravely on that same day, "Nay, I don't mind that my father should love you - but I pray - pray for your souls."

Philippa was now Queen of Portugal with five children of her own. She had written Katherine a gentle affectionate letter of congratulation upon receiving news of the marriage.

There had been another child on that old mossy stone bench that day. Katherine had an instant vision of the upturned dark grey eyes and dismissed it sharply. It was morbid to dwell on the one sorrow when the other five children were secure now in positions never imagined in her most daring dreams.

The next morning, when Katherine awoke early in the State Bed of the White Chamber, John still slept. He needed more rest than he used to, and though she tried to deny it to herself, nor ever let him guess that she noticed, she knew that his heart was tiring. He must mount stairs slowly, or struggle to breathe; at times his mouth had a pinched bluish look, and there was an oppression in his chest.

Yet on this summer morning he looked well, the deep grooves on his forehead and cheeks were smoothed by sleep, the scarred eyelid less puckered. He was thin but still hard and muscular, the hairs on his chest were golden as they used to be, though his head was streaked with grey. He slept tidily without sound, the fastidiousness that she loved in him never failed. She thought of what Elizabeth had said when she saw her father in Richard's coronation procession, "He's never slobbery, no matter what," and, smiling, kissed him on the shoulder, then slid out of bed and summoned Hawise.

Hawise was a person of consequence now, and not sure that she liked it. She had four waiting-women under her, besides a score of maidservants, and her new position required that she dress in heavy flowing woollen robes no matter what the temperature.

Katherine gestured towards the garde-robe, and the woman went in there so as not to disturb the Duke.

"I've brought ye spiced hippocras the butler sent up," said Hawise crossly, putting a chased gold ewer down on the toilet-table. "We're all far too grand to drink honest English ale of a morning anymore."

Katherine laughed. "Don't tell me you miss Kettlethorpe, my lass?" She swallowed a cupful of the cool sweet wine and began to wash herself with rose-water.

"Not sure I don't," grumbled Hawise, mixing powdered coral and myrrh for the tooth cleaning. "Doesn't take five women to wait on you, when I've done it well enough alone these donkey's years - that Dame Griselda Moorehead, Dame Muttonhead I call her, telling me it's her right and privilege to attend ye at your bath, that I know naught of etiquette. I'll right-and-privilege her, may Saint Anthony's fire burn me if I won't. 'Fishmongress' she calls me, as though Father's trade was aught to be 'shamed of!"

"Have some hippocras," said Katherine pacifically, putting the cup in Hawise's reluctant hand. "'Tis really delicious. We must both put up with changed conditions for ill or well - I suppose."

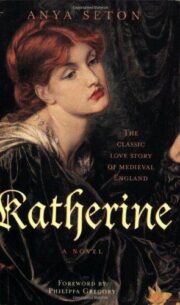

"Katherine" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Katherine". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Katherine" друзьям в соцсетях.