The nausea hits, fast, like a wave I had my back to. And then there’s puke all over my bloodied shirt. The nurse is quick with the basin, but not quick enough. She gives me a towel to clean myself with. The doctor is saying something about nausea and concussions. There are tears in my eyes. I never did learn to throw up without crying.

The nurse mops my face with another towel. “Oh, I missed a spot,” she says with a tender smile. “There, on your watch.”

On my wrist is a watch, bright and gold. It’s not mine. For the quickest moment, I see it on a girl’s wrist. I travel up the hand to a slender arm, a strong shoulder, a swan’s neck. When I get to the face, I expect it to be blank, like the faces in the dream. But it’s not.

Black hair. Pale skin. Warm eyes.

I look at the watch again. The crystal is cracked but it’s still ticking. It reads nine. I begin to suspect what it is I’ve forgotten.

I try to sit up. The world turns to soup.

The doctor pushes me back onto the bed, a hand on my shoulder. “You are agitated because you are confused. This is all temporary, but we will need to take the CT scan to make sure there is no bleeding on the brain. While we wait, we can attend to your facial lacerations. First I will give you something to make the area numb.”

The nurse swabs off my cheek with something orange. “Do not worry. This won’t stain.”

It doesn’t stain; it just stings.

• • •

“I think I should go now,” I say when the sutures are done.

The doctor laughs. And for a second I see white skin covered in white dust, but warmer underneath. A white room. A throbbing in my cheek.

“Someone is waiting for me.” I don’t know who, but I know it’s true.

“Who is waiting for you?” the doctor asks.

“I don’t remember,” I admit.

“Mr. de Ruiter. You must have a CT scan. And, after, I would like to keep you for observation until your mental clarity returns. Until you know who it is who waits for you.”

Neck. Skin. Lips. Her fragile-strong hand over my heart. I touch my hand to my chest, over the green scrub shirt the nurse gave me after they cut off my bloody shirt to check for broken ribs. And the name, it’s almost right there.

Orderlies come to wheel me to a different floor. I’m loaded into a metal tube that clatters around my head. Maybe it’s the noise, but inside the tube, the fog begins to burn off. But there is no sunshine behind it, only a dull, leaden sky as the fragments click together. “I need to go. Now!” I shout from the tube.

There’s silence. Then the click of the intercom. “Please hold still,” a disembodied voice orders in French.

• • •

I am wheeled back downstairs to wait. It is past twelve o’clock.

I wait more. I remember hospitals, remember exactly why I hate them.

I wait more. I am adrenaline slammed into inertia: a fast car stuck in traffic. I take a coin out of my pocket and do the trick Saba taught me as a little boy. It works. I calm down, and when I do, more of the missing pieces slot into place. We came together to Paris. We are together in Paris. I feel her hand gentle on my side, as she rode on the back of the bicycle. I feel her not-so-gentle hand on my side, as we held each other tight. Last night. In a white room.

The white room. She is in the white room, waiting for me.

I look around. Hospital rooms are never white like people believe. They are beige, taupe, mauve: neutral tones meant to soothe heartbreak. What I wouldn’t give to be in an actual white room right now.

• • •

Later, the doctor comes back in. He is smiling. “Good news! There is no subdural bleeding. Only a concussion. How is your memory?”

“Better.”

“Good. We will wait for the police. They will take your statement and then I can release you to your friend. But you must take it very easy. I will give you an instruction sheet for care, but it is in French. Perhaps someone can translate it, or we can find you one in English or Dutch online.”

“Ce ne sera pas nécessaire,” I say.

“Ahh, you speak French?” he asks in French.

I nod. “It came back to me.”

“Good. Everything else will, too.”

“So I can go?”

“Someone must come for you! And you have to make a report to the police.”

Police. It will be hours. And I have nothing to tell them, really. I take the coin back out and play it across my knuckle. “No police!”

The doctor follows the coin as it flips across my hand. “Do you have problems with the police?” he asks.

“No. It’s not that. I have to find someone,” I say. The coin clatters to the floor.

The doctor picks it up and hands it to me. “Find who?”

Perhaps it’s the casual way he asked; my bruised brain doesn’t have time to scramble it before spitting it out. Or perhaps the fog is lifting now, and leaving a terrific headache behind. But there it is, a name, on my lips, like I say it all the time.

“Lulu.”

“Ahh, Lulu. Très bien!” The doctor claps his hands together. “Let us call this Lulu. She can come get you. Or we can bring her to you.”

It is too much to explain that I don’t know where Lulu is. Only that she’s in the white room and she’s waiting for me and she’s been waiting for a long time. And I have this terrible feeling, and it’s not just because I’m in a hospital where things are routinely lost, but because of something else.

“I have to go,” I insist. “If I don’t go now, it could be too late.”

The doctor looks at the clock on the wall. “It is not yet two o’clock. Not late at all.”

“It might be too late for me.” Might be. As if whatever is going to happen hasn’t already happened.

The doctor looks at me for a long minute. Then he shakes his head. “It is better to wait. A few more hours, your memory will return, and you will find her.”

“I don’t have a few hours!”

I wonder if he can keep me here against my will. I wonder if at this moment I even have a will. But something pulls me forward, through the mist and the pain. “I have to go,” I insist. “Now.”

The doctor looks at me and sighs. “D’accord.” He hands me a sheaf of papers, tells me I am to rest for the next two days, clean my wound every day, the sutures will dissolve. Then he hands me a small card. “This is the police inspector. I will tell him to expect your call tomorrow.”

I nod.

“You have somewhere to go?” he asks.

Céline’s club. I recite the address. The Métro stop. These I remember easily. These I can find.

“Okay,” the doctor says. “Go to the billing office to check out, and then you may go.”

“Thank you.”

He touches me on the shoulder, reminds me to take it easy. “I am sorry Paris brought you such misfortune.”

I turn to face him. He’s wearing a name tag and the blurriness in my vision has subsided so I can focus on it. docteur robinet, it reads. And while my vision is okay, the day is still muddy, but I get this feeling about it. A hazy feeling of something—not quite happiness, but solidness, stepping on earth after being at sea for too long—fills me up. It tells me that whoever this Lulu is, something happened between us in Paris, something that was the opposite of misfortune.

Two

At the billing office, I fill out a few thousand forms. There are problems when they ask for an address. I don’t have one. I haven’t for such a long time. But they won’t let me leave until I supply one. At first, I think to give them Marjolein, my family’s attorney. She’s who Yael has deal with all her important mail, and whom, I realize too late, I was supposed to meet with today—or was it tomorrow? Or yesterday now?—in Amsterdam. But if a hospital bill goes to Marjolein, then all of this goes straight back to Yael, and I don’t want to explain it to her. I don’t want to not explain it, either, in the more likely event she never asks about it.

“Can I give you a friend’s address?” I ask the clerk.

“I don’t care if you give me the Queen of England’s address so long as we have somewhere to mail the bill,” she says.

I can give them Broodje’s address in Utrecht. “One moment,” I say.

“Take your time, mon chéri.”

I lean on the counter and rifle through my address book, flipping through the last year of accumulated acquaintances. There are countless names of people I don’t remember, names I didn’t remember even before I got this nasty bump on my head. There’s a message to Remember the caves in Matala. I do remember the caves, and the girl who wrote the message, but not why I’m supposed to remember them.

I find Robert-Jan’s address right at the front. I read it to the clerk, and as I close the book it falls open to one of the last pages. There’s all this unfamiliar writing, and at first I think my eyesight must really be messed up, but then I realize it’s just that the words are not English or Dutch but Chinese.

And for a second, I’m not here in this hospital, but I’m on a boat, with her, and she’s writing in my notebook. I remember. She spoke Chinese. She showed it to me. I turn the page, and there’s this.

There’s no translation next to it, but I somehow know what that character means.

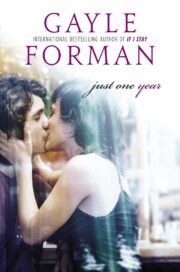

"Just One Year" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Just One Year". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Just One Year" друзьям в соцсетях.