"I think nothing, but I cannot sleep."

"You are chilled, crouched there in your cloak with a stone behind your head. I am little better myself, but there is no draught here from a crevice in the rock. We would do well if we gave our warmth to one another."

"No, I am not cold."

"I make the suggestion because I understand something of the night," he said; "the coldest hour comes before the dawn. You are unwise to sit alone. Come and lean against me, back to back, and sleep then if you will. I have neither the mind nor the desire to touch you."

She shook her head in reply and pressed her hands together beneath her cloak. She could not see his face, for he sat in shadow, with his profile turned to her, but she knew that he was smiling in the darkness and mocked her for her fear. She was cold, as he had said, and her body craved for warmth, but she would not go to him for protection. Her hands were numb now, and her feet had lost all feeling, and it was as though the granite had become part of her and held her close. Her brain kept falling on and off into a dream, and he walked into it, a giant, fantastic figure with white hair and eyes, who touched her throat and whispered in her ear. She came to a new world, peopled with his kind, who barred her progress with outstretched arms; and then she would wake again, stung to reality by the chill wind on her face, and nothing had changed, neither the darkness nor the mist, nor the night itself, and only sixty seconds gone in time.

Sometimes she walked with him in Spain, and he picked her monstrous flowers with purple heads, smiling on her the while; and when she would have thrown them from her they clung about her skirt like tendrils, creeping to her neck, fastening upon her with poisonous, deadly grip.

Or she would ride beside him in a coach, squat and black like a beetle, and the walls closed in upon them both, squeezing them together, pressing the life and breath from their bodies until they were flat, and broken, and destroyed, and lay against one another, poised into eternity, like two slabs of granite.

She woke from this last dream to certainty, feeling his hand upon her mouth, and this time it was no hallucination of her wandering mind, but grim reality. She would have struggled with him, but he held her fast, speaking harshly in her ear and bidding her be still.

He forced her hands behind her back and bound them, neither hastily nor brutally, but with cool and calm deliberation, using his own belt. The strapping was efficient but not painful, and he ran his finger under the belt to satisfy himself that it would not chafe her skin.

She watched him helplessly, feeling his eyes with her own, as though by doing so she might anticipate a message from his brain.

Then he took a handkerchief from the pocket of his coat and folded it and placed it in her mouth, knotting it behind her head, so that speech or cry was now impossible, and she must lie there, waiting for the next move in the game. When he had done this he helped her to her feet, for her legs were free and she could walk, and he led her a little way beyond the granite boulders to the slope of the hill. "I have to do this, Mary, for both our sakes," he said. "When we set forth last night upon this expedition I reckoned without the mist. If I lose now, it will be because of it. Listen to this, and you will understand why I have bound you, and why your silence may save us yet."

He stood on the edge of the hill, holding her arm, and pointing downwards to the white mist below. "Listen," he said again. "Your ears may be sharper than mine."

She knew now she must have slept longer than she thought, for the darkness had broken above their heads and morning had come. The clouds were low, and straggled across the sky as though interwoven with the mist, while to the east a faint glow heralded the pale, reluctant sun.

The fog was with them still and hit the moors below like a white blanket. She followed the direction of his hand and could see nothing but mist and the soaking stems of heather. Then she listened, as he had bidden her, and far away, from beneath the mist, there came a sound between a cry and a call, like a summons in the air. It was too faint at first to distinguish, and the tone was strangely pitched, unlike a human voice, unlike the shouting of men. It came nearer, rending the air with some excitement, and Francis Davey turned to Mary, the fog still white on his lashes and his hair. "Do you know what it is?" he said.

She stared back at him and shook her head, nor could she have told him had speech been possible. She had never heard the sound before. He smiled, then, a slow grim smile that cut into his face like a wound.

"I heard once, and I had forgotten it, that the squire of North Hill keeps bloodhounds in his kennels. It is a pity for both of us, Mary, that I did not remember."

She understood; and with a sudden comprehension of that distant eager clamour she looked up at her companion, horror in her eyes, and from him to the two horses, standing patiently as ever by the slabs of stone.

"Yes," he said, following her glance, "we must let them loose and drive them down to the moors below. They can serve us no longer now and would only bring the pack upon us. Poor Restless, you would betray me once again."

She watched him, sick at heart, as he released the horses and led them to the steep slope of the hill. Then he bent to the ground, gathering stones in his hands, and rained blow after blow upon their flanks, so that they slipped and stumbled amongst the wet bracken on the hillside; and then, when his onslaught continued and their instinct jogged them into action, they fled, snorting with terror, down the steep slope of the tor, dislodging boulders and earth in their descent, and so plunged out of sight into the white mists below. The baying of the hounds came nearer now, deep-pitched and persistent, and Francis Davey ran to Mary, stripping himself of his long black coat that hung about his knees and throwing his hat into the heather.

"Come," he said. "Friend or enemy, we share a common danger now."

They scrambled up the hill amongst the boulders and the slabs of granite, he with his arm about her, for her bound hands made progress difficult; and they waded in and out of crevice and rock, knee deep in soaking bracken and black heather, climbing ever higher and higher to the great peak of Rough Tor. Here, on the very summit, the granite was monstrously shaped, tortured and twisted into the semblance of a roof, and Mary lay beneath the great stone slab, breathless, and bleeding from her scratches, while he climbed above her, gaining foothold in the hollows of the stone. He reached down to her, and, though she shook her head and made sign that she could climb no further, he bent and dragged her to her feet again, cutting at the belt that bound her and tearing the handkerchief from her mouth.

"Save yourself, then, if you can," he shouted, his eyes burning in his pale face, his white halo of hair blowing in the wind. She clung to a table of stone some ten feet from the ground, panting and exhausted, while he climbed above her and beyond, his lean black figure like a leech on the smooth surface of the rock. The baying of the hounds was unearthly and inhuman, coming as it did from the blanket of fog below, and the chorus was joined now by the cries and the shouting of men, a turmoil of excitement that filled the air with sound and was the more terrible because it was unseen. The clouds moved swiftly across the sky, and the yellow glow of the sun swam into view above a breath of mist. The mist parted and dissolved. It rose from the ground in a twisting column of smoke, to be caught up in the passing clouds, and the land that it had covered for so long stared up at the sky pallid and newborn. Mary looked down upon the sloping hillside; and there were little dots of men standing knee deep in the heather, the light of the sun shining upon them, while the yelping hounds, crimson-brown against the grey stone, ran before them like rats amongst the boulders.

They came fast upon the trail, fifty men or more, shouting and pointing to the great tablets of stone; and, as they drew near, the clamour of the hounds echoed in the crevices and whined in the caves.

The clouds dissolved as the mist had done, and a patch of sky, larger than a man's hand, showed blue above their heads.

Somebody shouted again, and a man who knelt in the heather, scarcely fifty yards from Mary, lifted his gun to his shoulder and fired.

The shot spat against the granite boulder without touching her, and when he rose to his feet she saw that the man was Jem, and he had not seen her.

He fired again, and this time the shot whistled close to her ear, and she felt the breath of its passing upon her face.

The hounds were worming in and out amidst the bracken, and one of them leapt at the jutting rock beneath her, his great muzzle snuffling the stone. Then Jem fired once more; and, looking beyond her, Mary saw the tall black figure of Francis Davey outlined against the sky, standing upon a wide slab like an altar, high above her head. He stood for a moment poised like a statue, his hair blowing in the wind; and then he flung out his arms as a bird throws his wings for flight, and drooped suddenly and fell; down from his granite peak to the wet dank heather and the little crumbling stones.

Chapter 18

It was a hard, bright day in early January. The ruts and holes in the highroad, which were generally inches thick in mud or water, were covered with a thin layer of ice, and the wheel tracks were hoary with frost.

This same frost had laid a white hand upon the moors themselves, and they stretched to the horizon pale and indefinite in colour, a poor contrast to the clear blue sky above. The texture of the ground was crisp, and the short grass crunched beneath the foot like shingle. In a country of lane and hedgerow the sun would have shone warmly, with a make-belief of spring, but here the air was sharp and cutting to the cheek, and everywhere upon the land was the rough, glazed touch of winter. Mary walked alone on Twelve Men's Moor, with the keen wind slapping her face, and she wondered why it was that Kilmar, to the left of her, had lost his menace and was now no more than a black scarred hill under the sky. It might be that anxiety had blinded her to beauty, and she had made confusion in her mind with man and nature; the austerity of the moors had been strangely interwoven with the fear and hatred of her uncle and Jamaica Inn. The moors were bleak still, and the hills were friendless, but their old malevolence had vanished, and she could walk upon them with indifference.

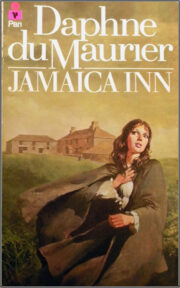

"Jamaica Inn" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Jamaica Inn". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Jamaica Inn" друзьям в соцсетях.