"I most certainly am not. Warleggan is a long trek from North Hill, but I daresay he can find his way in the dark."

"What has it to do with you if he visits the blacksmith?"

"He will show the nail he picked up in the heather, down in the field below Jamaica Inn. The nail comes from a horse's shoe; the job was carelessly done, of course. The nail was a new one, and Jem Merlyn, being a stealer of horses, knows the work of every blacksmith on the moors. 'Look here,' he said to the squire. 'I found it this morning in the field behind the inn. Now you have had your discussions and want me no more, I'll ride to Warleggan, with your leave, and throw this in Tom Jory's face as bad workmanship."

"Well, and what then?" said Mary.

"Yesterday was Sunday, was it not? And on Sunday no blacksmith plies his trade unless he has great respect for his customer. Only one traveller passed Tom Jory's smithy yesterday and begged a new nail for his lame horse, and the time was, I suppose, somewhere near seven o'clock in the evening. After which the traveller continued his journey by way of Jamaica Inn."

"How do you know this?" said Mary.

"Because the traveller was the vicar of Altarnun," he said.

Chapter 17

A silence had fallen upon the room. Although the fire burnt steady as ever, there was a chill in the air that had not been there before. Each waited for the other to speak, and Mary heard Francis Davey swallow once. At length she looked into his face and saw what she expected: the pale, steadfast eyes staring at her across the table, cold no longer, but burning in the white mask of his face like living things at last. She knew now what he would have her know, but still she said nothing; she clung to ignorance as a source of protection, playing for time as the only ally in her favour.

His eyes compelled her to speak, and she continued to warm her hands at the fire, forcing a smile. "You are pleased to be mysterious tonight, Mr. Davey."

He did not answer at once; she heard him swallow again, and then he leant forward in his chair, with an abrupt change of subject.

"You lost your confidence in me today before I came," he said. "You went to my desk and found the drawing; you were disturbed. No, I did not see you; I am no keyhole watcher; but I saw that the paper had been moved. You said to yourself, as you have said before, 'What manner of man is this vicar of Altarnun?' and when you heard my footsteps on the path you crouched in your chair there, before the fire, rather than look upon my face. Don't shrink from me, Mary Yellan; there is no longer any need for pretence between us, and we can be frank with one another, you and I."

Mary turned to him and then away again; there was a message in his eyes she feared to read. "I am very sorry I went to your desk," she said; "such an action was unforgivable, and I don't yet know how I came to it. As for the drawing, I am ignorant of such things, and whether it be good or bad I cannot say."

"Never mind if it be good or bad, the point was that it frightened you?"

"Yes, Mr. Davey, it did."

"You said to yourself again, "This man is a freak of nature, and his world is not my world.' You were right there, Mary Yellan. I live in the past, when men were not so humble as they are today. Oh, not your heroes of history in doublet and hose and narrow-pointed shoes — they were never my friends — but long ago in the beginning of time, when the rivers and the sea were one, and the old gods walked the hills."

He rose from his chair and stood before the fire, a lean black figure with white hair and eyes, and his voice was gentle now, as she had known it first.

"Were you a student, you would understand," he said, "but you are a woman, living already in the nineteenth century, and because of this my language is strange to you. Yes, I am a freak in nature and a freak in time. I do not belong here, and I was born with a grudge against the age, and a grudge against mankind. Peace is very hard to find in the nineteenth century. The silence is gone, even on the hills. I thought to find it in the Christian Church, but the dogma sickened me, and the whole foundation is built upon a fairy tale. Christ himself is a figurehead, a puppet thing created by man himself.

"However, we can talk of these things later, when the heat and turmoil of pursuit are not upon us. We have eternity before us. One thing at least, we have no traps or baggage, but can travel light, as they travelled of old."

Mary looked up at him, her hands gripping the sides of her chair.

"I don't understand you, Mr. Davey."

"Why, yes, you understand me very well. You know by now that I killed the landlord of Jamaica Inn, and his wife, too; nor would the pedlar have lived had I known of his existence. You have pieced the story together in your own mind while I talked to you just now. You know that it was I who directed every move made by your uncle and that he was a leader in name alone. I have sat here at night, with him in your chair there and the map of Cornwall spread out on the table before us. Joss Merlyn, the terror of the countryside, twisting his hat in his hands and touching his forelock when I spoke to him. He was like a child in the game, powerless without my orders, a poor blustering bully that hardly knew his right hand from his left. His vanity was like a bond between us, and the greater his notoriety amongst his companions the better was he pleased. We were successful, and he served me well; no other man knew the secret of our partnership.

"You were the block, Mary Yellan, against which we stubbed our toes. With your wide enquiring eyes and your gallant inquisitive head, you came amongst us, and I knew that the end was near. In any case, we had played the game to its limit, and the time had come to make an end. How you pestered me with your courage and your conscience, and how I admired you for it! Of course you must hear me in the empty guest room at the inn, and must creep down to the kitchen and see the rope upon the beam: that was your first challenge.

"And then you steal out upon the moor after your uncle, who had tryst with me on Rough Tor, and, losing him in the darkness, stumble upon myself and make me confidant. Well, I became your friend, did I not, and gave you good advice? Which, believe me, could not have been bettered by a magistrate himself. Your uncle knew nothing of our strange alliance, nor would he have understood. He brought his own death upon himself by disobedience. I knew something of your determination, and that you would betray him at the first excuse. Therefore he should give you none, and time alone would quiet your suspicions. But your uncle must drink himself to madness on Christmas Eve, and, blundering like a savage and a fool, set the whole country in a blaze. I knew then he had betrayed himself and with the rope around his neck would play his last card and name me master. Therefore he had to die, Mary Yellan, and your aunt, who was his shadow; and, had you been at Jamaica Inn last night when I passed by, you too — No, you would not have died."

He leant down to her, and, taking her two hands, he pulled her to her feet, so that she stood level with him, looking in his eyes.

"No," he repeated, "you would not have died. You would have come with me then as you will come tonight."

She stared back at him, watching his eyes. They told her nothing — they were clear and cold as they had been before — but his grip upon her wrists was firm and held no promise of release.

"You are wrong," she said; "you would have killed me then as you will kill me now. I am not coming with you, Mr. Davey."

"Death to dishonour?" he said, smiling, the thin line breaking the mask of his face. "I face you with no such problem. You have gained your knowledge of the world from old books, Mary, where the bad man wears a tail beneath his cloak and breathes fire through his nostrils. You have proved yourself a dangerous opponent, and I prefer you by my side; there, that is a tribute. You are young, and you have a certain grace which I should hate to destroy. Besides, in time we will take up the threads of our first friendship, which has gone astray tonight."

"You are right to treat me as a child and a fool, Mr. Davey," said Mary. "I have been both since I stumbled against your horse that evening. Any friendship we may have shared was a mockery and a dishonour, and you gave me counsel with the blood of an innocent man scarce dry upon your hands. My uncle at least was honest; drunk or sober, he blurted his crimes to the four winds, and dreamt of them by night — to his terror. But you — you wear the garments of a priest of God to shield you from suspicion; you hide behind the Cross. You talk to me of friendship—"

"Your revolt and your disgust please me the more, Mary Yellan," he replied. "There is a dash of fire about you that the women of old possessed. Your companionship is not a thing to be thrown aside. Come, let us leave religion out of our discussion. When you know me better we will return to it, and I will tell you how I sought refuge from myself in Christianity and found it to be built upon hatred, and jealousy, and greed — all the man-made attributes of civilization, while the old pagan barbarism was naked and clean.

"I have had my soul sickened…. Poor Mary, with your feet fast in the nineteenth century and your bewildered faun face looking up to mine, who admit myself a freak of nature and a shame upon your little world. Are you ready? Your cloak hangs in the hall, and I am waiting."

She backed to the wall, her eyes upon the clock; but he still held her wrists and tightened his grip upon them.

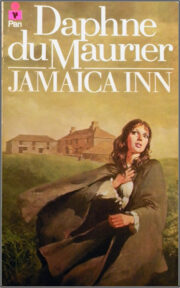

"Jamaica Inn" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Jamaica Inn". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Jamaica Inn" друзьям в соцсетях.