Mary cut herself a slice of cake she did not want and forced it between her lips. By making a pretence of eating she gave herself countenance. The hand shook, though, that held the knife, and she made a poor job of her slice.

"I don't see," she said, "what I have to do in the matter."

"You have too modest an opinion of yourself," he replied. They continued to eat in silence, Mary with lowered head and eyes firm fixed upon her plate. Instinct told her that he played her as an angler plays the fish upon his line. At last she could wait no longer, but must blurt him a question: "So Mr. Bassat and the rest of you have made little headway, after all, and the murderer is still at large?"

"Oh, but we have not moved as slowly as that. Some progress has been made. The pedlar, for instance, in a hopeless attempt to save his own skin, has turned King's evidence to the best of his ability, but he has not helped us much. We have had from him a bald account of the work done on the coast on Christmas Eve — in which, he says, he took no part — and also some patching together of the long months that have gone before. We heard of the waggons that came to Jamaica Inn by night among other things, and we were given the names of his companions. Those he knew, that is to say. The organisation appears to have been far larger than was hitherto supposed."

Mary said nothing. She shook her head when he offered her the damsons.

"In fact," continued the vicar, "he went so far as to suggest that the landlord of Jamaica Inn was their leader in name only, and that your uncle had his orders from one above him. That, of course, puts a new complexion on the matter. The gentlemen became excited and a little disturbed. What have you to say of the pedlar's theory?"

"It is possible, of course."

"I believe you once made the same suggestion to me?"

"I may have done. I forget."

"If this is so, it would seem that the unknown leader and the murderer must be one and the same person. Don't you agree?"

"Why, yes, I suppose so."

"That should narrow the field considerably. We may disregard the general rabble of the company and look for someone with a brain and a personality. Did you ever see such a person at Jamaica Inn?"

"No, never."

"He must have gone to and fro in stealth, possibly in the silence of the night when you and your aunt were abed and asleep. He would not have come by the highroad, because you would have heard the clatter of his horse's hoofs. But there is always the possibility that he came on foot, is there not?"

"Yes, there is always that possibility, as you say."

"In which case the man must know the moors, or at least have local knowledge. One of the gentlemen suggested that he lived near by — within walking or riding distance, that is to say. And that is why Mr. Bassat intends to question every inhabitant in the radius of ten miles, as I explained to you at the beginning of supper. So you see the net will close around the murderer, and if he tarries long he will be caught. We are all convinced of that. Have you finished already? You have eaten very little."

"I am not hungry."

"I am sorry for that. Hannah will think her cold pie was not appreciated. Did I tell you I saw an acquaintance of yours today?"

"No, you did not. I have no friends but yourself."

"Thank you, Mary Yellan. That is a pretty compliment, and I shall treasure it accordingly. But you are not being strictly truthful, you know. You have an acquaintance; you told me so yourself."

"I don't know who you mean, Mr. Davey."

"Come now. Did not the landlord's brother take you to Launceston fair?"

Mary gripped her hands under the table and dug her nails into her flesh.

"The landlord's brother?" she repeated, playing for time. "I have not seen him since then. I believed him to be away."

"No, he has been in the district since Christmas. He told me so himself. As a matter of fact, it had come to his ears that I had given you shelter, and he came up to me with a message for you. Tell her how sorry I am.' That is what he said. I presume he referred to your aunt."

"Was that all he said?"

"I believe he would have said more, but Mr. Bassat interrupted us."

"Mr. Bassat? Mr. Bassat was there when he spoke to you?"

"Why, of course. There were several of the gentlemen in the room. It was just before I came away from North Hill this evening, when the discussion was closed for the day."

"Why was Jem Merlyn present at the discussion?"

"He had a right, I suppose, as brother of the deceased. He did not appear much moved by his loss, but perhaps they did not agree."

"Did — did Mr. Bassat and the gentlemen question him?"

"There was a considerable amount of talk amongst them the whole day. Young Merlyn appears to possess intelligence. His answers were most astute. He must have a far better brain than his brother ever had. You told me he lived somewhat precariously, I remember. He stole horses, I believe."

Mary nodded. Her fingers traced a pattern on the tablecloth.

"He seems to have done that when there was nothing better to do," said the vicar, "but when a chance came for him to use his intelligence he took it, and small blame to him, I suppose. No doubt he was well paid."

The gentle voice wore away at her nerves, pinpricking them with every word, and she knew now that he had defeated her, and she could no longer keep up the pretence of indifference. She lifted her face to him, her eyes heavy with the agony of restraint, and she spread out her hands in supplication.

"What will they do to him, Mr. Davey?" she said. "What will they do to him?"

The pale, expressionless eyes stared back at her, and for the first time she saw a shadow pass across them, and a flicker of surprise.

"Do?" he said, obviously puzzled. "Why should they do anything? I suppose he has made his peace with Mr. Bassat and has nothing more to fear. They will hardly throw old sins in his face after the service he has done them."

"I don't understand you. What service has he done?"

"Your mind works slowly tonight, Mary Yellan, and I appear to talk in riddles. Did you not know that it was Jem Merlyn who informed against his brother?"

She stared at him stupidly, her brain clogged and refusing to work. She repeated the words after him like a child who learns a lesson.

"Jem Merlyn informed against his brother?"

The vicar pushed away his plate and began to set the things in order on the tray. "Why, certainly," he said; "so Mr. Bassat gave me to understand. It appears that it was the squire himself who fell in with your friend at Launceston on Christmas Eve and carried him off to North Hill, as an experiment. 'You've stolen my horse,' said he, 'and you're as big a rogue as your brother. I've the power to clap you in jail tomorrow and you wouldn't set eyes on a horse for a dozen years or more. But you can go free if you bring me proof that your brother at Jamaica Inn is the man I believe him to be.'

"Your young friend asked for time; and when the time was up he shook his head. 'No,' said he; 'you must catch him yourself if you want him. I'm damned if I'll have truck with the law.' But the squire pushed a proclamation under his nose. 'Look there, Jem,' he said, 'and see what you think of that. There's been the bloodiest wreck on Christmas Eve since the Lady of Gloucester went ashore above Padstow last winter. Now will you change your mind?' As to the rest of the story, the squire said little in my hearing — people were coming and going all the time, you must remember — but I gather your friend slipped his chain and ran for it in the night, and then came back again yesterday morning, when they thought to have seen the last of him, and went straight to the squire as he came out of church and said, as cool as you please, 'Very well, Mr. Bassat, you shall have your proof.' And that is why I remarked to you just now that Jem Merlyn had a better brain than his brother."

The vicar had cleared the table and set the tray in the corner, but he continued to stretch his legs before the fire and take his ease in the narrow high-backed chair. Mary took no account of his movements. She stared before her into space, her whole mind split, as it were, by his information, the evidence she had so fearfully and so painfully built against the man she loved collapsing into nothing like a pack of cards.

"Mr. Davey," she said slowly, "I believe I am the biggest fool that ever came out of Cornwall."

"I believe you are, Mary Yellan," said the vicar.

His dry tone, so cutting after the gentle voice she knew, was a rebuke in itself, and she accepted it with humility.

"Whatever happens," she continued, "I can face the future now, bravely and without shame."

"I am glad of that," he said.

She shook her hair back from her face and smiled for the first time since he had known her. The anxiety and the dread had gone from her at last.

"What else did Jem Merlyn say and do?" she asked.

The vicar glanced at his watch and replaced it with a sigh.

"I wish I had the time to tell you," he said, "but it is nearly eight already. The hours go by too fast for both of us. I think we have talked enough about Jem Merlyn for the present."

"Tell me one thing — was he at North Hill when you left?"

"He was. In fact, it was his last remark that hurried me home."

"What did he say to you?"

"He did not address himself to me. He announced his intention of riding over tonight to visit the blacksmith at Warleggan."

"Mr. Davey, you are playing with me now."

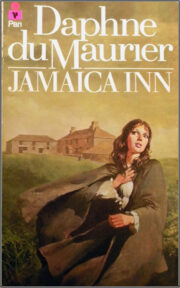

"Jamaica Inn" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Jamaica Inn". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Jamaica Inn" друзьям в соцсетях.