The light of her candle played upon the walls, but it did not reach to the top of the stairs, where the darkness gaped at her like a gulf.

She knew she could never climb those stairs again, nor tread that empty landing. Whatever lay beyond her and above must rest there undisturbed. Death had come upon the house tonight, and its brooding spirit still hovered in the air. She felt now that this was what Jamaica Inn had always waited for and feared. The damp walls, the creaking boards, the whispers in the air, and the footsteps that had no name: these were the warnings of a house that had felt itself long threatened.

Mary shivered; and she knew that the quality of this silence had origin in far-off buried and forgotten things.

She dreaded panic, above all things; the scream that forced itself to the lips, the wild stumble of groping feet and hands that beat the air for passage. She was afraid that it might come to her, destroying reason; and, now that the first shock of discovery had lessened, she knew that it might force its way upon her, close in and stifle her. Her fingers might lose their sense of grip and touch, and the candle fall from her hands. Then she would be alone and covered by the darkness. The tearing desire to run seized hold of her, and she conquered it. She backed away from the hall towards the passage, the candle flickering in the draught of air, and when she came to the kitchen and saw the door still open to the patch of garden, her calm deserted her, and she ran blindly through the door to the cold free air outside, a sob in her throat, her outstretched hands grazing the stone wall as she turned the corner of the house. She ran like a thing pursued across the yard and came to the open road, where the familiar stalwart figure of the squire's groom confronted her. He put out his hands to save her, and she groped at his belt, feeling for security, her teeth chattering now in the full shock of reaction.

"He's dead," she said; "he's dead there on the floor. I saw him"; and, try as she did, she could not stop this chattering of her teeth and the shivering of her body. He led her to the side of the road, back to the trap, and he reached for the cloak and put it around her, and she held it to her close, grateful for the warmth.

"He's dead," she repeated; "stabbed in the back; I saw the place where his coat was rent, and there was blood. He lay on his face. The clock had fallen with him. The blood was dry; and he looked as though he had lain there for some time. The inn was dark and silent. No one else was there."

"Was your aunt gone?" whispered the man.

Mary shook her head. "I don't know. I did not see. I had to come away."

He saw by her face that her strength had gone and she would fall, and he helped her up into the trap and climbed onto the seat beside her.

"All right, then," he said, "all right. Sit quiet, then, here. No one shall hurt you. There now. All right, then." His gruff voice helped her, and she crouched beside him in the trap, the warm cloak muffled to her chin.

"That was no sight for a maid to see," he told her. "You should have let me go. I wish now you had stayed back here in the trap. That's terrible for you to see him lying dead there, murdered."

Talking eased her, and his rough sympathy was good. "The pony was still in the stable," she said. "I listened at the door and heard him move. They had never even finished their preparations for going. The kitchen door was unlocked, and there were bundles on the floor there; blankets too, ready to load into the cart. It must have happened several hours ago."

"It puzzles me what the squire is doing," said Richards. "He should have been here before this. I'd feel easier if he'd come and you could tell your story to him. There's been bad work here tonight. You should never have come."

They fell silent, and both of them watched the road for the coming of the squire.

"Who'd have killed the landlord?" said Richards, puzzled. "He's a match for most men and should have held his own. There was plenty who might have had a hand in it, though, for all that. If ever a man was hated, he was."

"There was the pedlar," said Mary slowly. "I'd forgotten the pedlar. It must have been him, breaking out from the barred room."

She fastened upon the idea, to escape from another; and she retold the story, eagerly now, of how the pedlar had come to the inn the night before. It seemed at once that the crime was proven and there could be no other explanation.

"He'll not run far before the squire catches him," said the groom; "you can be sure of that. No one can hide on these moors, unless he's a local man, and I have never heard of Harry the pedlar before. But, then, they came from every hole and corner in Cornwall, Joss Merlyn's men, by all accounts. They were, as you might say, the dregs of the country."

He paused, and then: "I'll go to the inn if you would care for me to, and see for myself if he has left any trace behind him. There might be something—"

Mary seized hold of his arm. "I'll not be alone again," she said swiftly. "Think me a coward if you will, but I could not stand it. Had you been inside Jamaica Inn you would understand. There's a brooding quiet about the place tonight that cares nothing for the poor dead body lying there."

"I can mind the time, before your uncle came there, when the house stood empty," said the servant, "and we'd take the dogs there after rats, for sport. We thought nothing of it then; just a lonely shell of a place it seemed, without a soul of its own. But the squire kept it in good repair, mind you, while he waited for a tenant. I'm a St. Neot man myself, and never came here until I served the squire, but I've been told in the old days there was good cheer and good company at Jamaica, with friendly, happy folk living in the house, and always a bed for a passing traveller upon the road. The coaches stayed here then, what never do now, and hounds would meet here once a week in Mr. Bassat's boyhood. Maybe these things will come again."

Mary shook her head. "I've only seen the evil," she said; "I've only seen the suffering there's been, and the cruelty, and the pain. When my uncle came to Jamaica Inn he must have cast his shadow over the good things, and they died." Their voices had sunk to a whisper, and they glanced half-consciously over their shoulders to the tall chimneys that stood out against the sky, clear-cut and grey, beneath the moon. They were both thinking of one thing, and neither had the courage to mention it first; the groom from delicacy and tact, Mary from fear alone. Then at last she spoke, her voice husky and low:

"Something has happened to my aunt as well; I know that; I know she is dead. That's why I was afraid to go upstairs. She is lying there in the darkness, on the landing above. Whoever killed my uncle will have killed her too."

The groom cleared his throat. "She may have run out onto the moor," he said, "she may have run for help along the road—"

"No," whispered Mary, "she would never have done that. She would be with him now, down in the hall there, crouching by his side. She is dead. I know she is dead. If I had not left her, this would never have happened."

The man was silent. He could not help her. After all, she was a stranger to him, and what had passed beneath the roof of the inn while she had lived there was no concern of his. The responsibility of the evening lay heavy enough upon his shoulders, and he wished that his master would come. Fighting and shouting he understood; there was sense in that; but if there had really been a murder, as she said, and the landlord lying dead there, and his wife too — why, they could do no good in staying here like fugitives themselves, crouching in the ditch, but were better off and away, and so down the road to sight and sound of human habitation.

"I came here by the orders of my mistress," he began awkwardly; "but she said the squire would be here. Seeing as he is not—"

Mary held up a warning hand. "Listen," she said sharply. "Can you hear something?"

They strained their ears to the north. The faint clop of horses was unmistakable, coming from beyond the valley, over the brow of the further hill.

"It's them," said Richards excitedly; "it's the squire; he's coming at last. Watch now; we'll see them go down the road into the valley."

They waited, and when a minute had passed, the first horseman appeared like a black smudge against the hard white road, followed by another, and another. They strung out in a line, and closed again, travelling at a gallop; while the cob who waited patiently beside the ditch pricked his ears and turned an enquiring head. The clatter drew near, and Richards in his relief ran out upon the road to greet them, shouting and waving his arms.

The leader swerved and drew rein, calling out in surprise at the sight of the groom. "What the devil do you do here?" he shouted, for it was the squire himself, and he held up his hand to warn his followers behind.

"The landlord is dead, murdered," cried the groom. "I have his niece here with me in the trap. It was Mrs. Bassat herself who sent me out here, sir. This young woman had best tell you the story in her own words."

He held the horse while his master dismounted, answering as well as he could the rapid questions put to him by the squire, and the little band of men gathered around him too, pressing for news; some of them dismounting also, and stamping their feet on the ground, blowing upon their hands for warmth.

"If the fellow has been murdered, as you say, then, by God, it serves him right," said Mr. Bassat; "but I'd rather have clapped irons on him myself for all that. You can't pay scores against a dead man. Go on into the yard, the rest of you, while I see if I can get some sense out of the girl yonder."

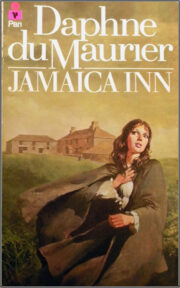

"Jamaica Inn" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Jamaica Inn". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Jamaica Inn" друзьям в соцсетях.