He nodded at her, reassuring her, smiling still, smirking and sly, and she felt his furtive hand fasten itself upon her. She moved swiftly, lashing out at him, and her fist caught him underneath the chin, shutting his mouth like a trap, with his tongue caught between his teeth. He squealed like a rabbit, and she struck him again, but this time he grabbed at her and lurched sideways upon her, all pretence of gentle persuasion gone, his strength horrible, his face drained of all colour. He was fighting now for possession, and she knew it, and, aware that his strength was greater than hers and must prevail in the end, she lay limp suddenly, to deceive him, giving him the advantage for the moment. He grunted in triumph, relaxing his weight, which was what she intended, and as he moved his position and lowered his head she jabbed at him swiftly with the full force of her knee, at the same time thrusting her fingers in his eyes. He doubled up at once, rolling onto his side in agony, and in a second she had struggled from under him and pulled herself to her feet, kicking at him once more as he rocked defenceless, his hands clasped to his belly. She grabbed in the ditch for a stone to fling at him, finding nothing but loose earth and sand, and she dug handfuls of this, scattering it in his face and in his eyes, so that he was blinded momentarily and could make no return. Then she turned again and began to run like a hunted thing up the twisting lane, her mouth open, her hands outstretched, tripping and stumbling over the ruts in the path; and when she heard his shout behind her once more, and the padding of his feet, a sense of panic swamped her reason and she started to climb up the high bank that bordered the lane, her foot slipping at every step in the soft earth, until with the very madness of effort born in terror she reached the top, and crawled, sobbing, through a gap in the thorn hedge that bordered the bank. Her face and her hands were bleeding, but she had no thought for this and ran along the cliff away from the lane, over tussocks of grass and humped uneven ground, all sense of direction gone from her, her one idea to escape from the thing that was Harry the pedlar.

A wall of fog closed in upon her, obscuring the distant line of hedge for which she had been making, and she stopped at once in her headlong rush, aware of the danger of sea mist, and how in its deception it might bring her back to the lane again. She fell at once upon hands and knees, and crawled slowly forward, her eyes low to the ground, following a narrow sandy track that wound in the direction she wished to take. Her progress was slow, but instinct told her that the distance was increasing between her and the pedlar, which was the only thing that mattered. She had no reckoning of time; it was three, perhaps four, in the morning, and the darkness would give no sign of breaking for many hours to come. Once more the rain came down through the curtain of mist, and it seemed as though she could hear the sea on every side of her and there were no escape from it; the breakers were muffled no longer; they were louder and clearer than before. She realised that the wind had been no guide to direction, for even now, with it behind her, it might have shifted a point or two, and with her ignorance of the coastline she had not turned east, as she had meant to do, but was even now upon the brink of a sagging cliff path that, judging by the sound of the sea, was taking her straight to the shore. The breakers, though she could not see them because of the fog, were somewhere beyond her in the darkness, and to her dismay she sensed they were on a level with her, and not beneath her. This meant that the cliffs here descended abruptly to the shore, and, instead of a long and tortuous path to a cove that she had pictured from the abandoned carriage, the gullyway must have been only a few yards from the sea itself. The banks of the gully had muffled the sound of the breakers. Even as she decided this, there was a gap in the mist ahead of her, showing a patch of sky. She crawled on uncertainly, the path widening and the fog clearing, and the wind veered in her face once more; and there she knelt amongst driftwood and seaweed and loose shingle, on a narrow strand, with the land sloping up on either side of her, while not fifty yards away, and directly in front of her, were the high combing seas breaking upon the shore.

After a while, when her eyes had accustomed themselves to the shadows, she made them out, huddled against a jagged rock that broke up the expanse of the beach: a little knot of men, grouped together for warmth and shelter, silently peering ahead of them into the darkness. Their very stillness made them the more menacing who had not been still before; and the attitude of stealth, the poise of their bodies, crouched as they were against the rock, the tense watchfulness of their heads turned one and all to the incoming sea, was a sight at once fearful and pregnant with danger.

Had they shouted and sung, called to one another, and made the night hideous with their clamour, their heavy boots resounding on the crunching shingle, it would have been in keeping with their character and with what she expected; but there was something ominous in this silence, which suggested that the crisis of the night had come upon them. A little jutting piece of rock stood between Mary and the bare exposed beach, and beyond this she dared not venture for fear of betraying herself. She crawled as far as the rock and lay down on the shingle behind it, while ahead of her, directly in her line of vision when she moved her head, stood her uncle and his companion, with their backs turned to her.

She waited. They did not move. There was no sound. Only the sea broke in its inevitable monotony upon the shore, sweeping the strand and returning again, the line of breakers showing thin and white against the black night.

The mist began to lift very slowly, disclosing the narrow outline of the bay. Rocks became more prominent, and the cliffs took on solidity. The expanse of water widened, opening from a gulf to a bare line of shore that stretched away interminably. To the right, in the distance, where the highest part of the cliff sloped to the sea, Mary made out a faint pinprick of light. At first she thought it a star, piercing the last curtain of dissolving mist, but reason told her that no star was white, nor ever swayed with the wind on the surface of a cliff. She watched it intently, and it moved again; it was like a small white eye in the darkness. It danced and curtseyed, storm tossed, as though kindled and carried by the wind itself, a living flare that would not be blown. The group of men on the shingle below heeded it not; their eyes were turned to the dark sea beyond the breakers.

And suddenly Mary was aware of the reason for their indifference, and the small white eye that had seemed at first a thing of friendliness and comfort, winking bravely alone in the wild night, became a symbol of horror.

The star was a false light placed there by her uncle and his companions. The pinprick gleam was evil now, and the curtsey to the wind became a mockery. In her imagination the light burnt fiercer, extending its beam to dominate the cliff, and the colour was white no more, but old and yellow like a scab. Someone watched by the light so that it should not be extinguished. She saw a dark figure pass in front of it, obscuring the gleam for a moment, and then it burnt clear again. The figure became a blot against the grey face of the cliff, moving quickly in the direction of the shore. Whoever it was climbed down the slope to his companions on the shingle. His action was hurried, as though time pressed him, and he was careless in the manner of his coming for the loose earth and stones slid away from under him, scattering down onto the beach below. The sound startled the men beneath, and for the first time since Mary had watched them they withdrew their attention from the incoming tide and looked up to him. Mary saw him put his hands to his mouth and shout, but his words were caught up in the wind and did not come to her. They reached the little group of men waiting on the shingle, who broke up at once in some excitement, some of them starting halfway up the cliff to meet him; but when he shouted again and pointed to the sea, they ran down towards the breakers, their stealth and silence gone for the moment, the sound of their footsteps heavy on the shingle, their voices topping one another above the crash of the sea. Then one of them — her uncle it was; she recognised his great loping stride and massive shoulders — held up his hand for silence; and they waited, all of them, standing upon the shingle with the waves breaking beyond their feet; spread out in a thin line they were, like crows, their black forms outlined against the white beach. Mary watched with them; and out of the mist and darkness came another pinprick of light in answer to the first. This new light did not dance and waver as the one on the cliff had done; it dipped low and was hidden, like a traveller weary of his burden, and then it would rise again, pointing high to the sky, a hand flung into the night in a last and desperate attempt to break the wall of mist that hitherto had defied penetration. The new light drew nearer to the first. The one compelled the other. Soon they would merge and become two white eyes in the darkness. And still the men crouched motionless upon the narrow strand, waiting for the lights to close with one another.

The second light dipped again; and now Mary could see the shadowed outline of a hull, the black spars like fingers spreading above it, while a white surging sea combed beneath the hull, and hissed, and withdrew again. Closer drew the mast light to the flare upon the cliff, fascinated and held, like a moth coming to a candle.

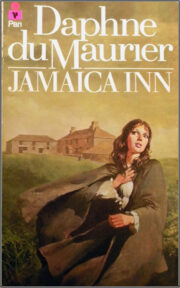

"Jamaica Inn" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Jamaica Inn". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Jamaica Inn" друзьям в соцсетях.