"I don't believe you," he said. "You started out with the hope of sighting me, and it's no use pretending any different. Well, you've come in good time to cook my dinner. There's a piece of mutton in the kitchen."

He led the way up the mud track, and, rounding the corner, they came to a small grey cottage built on the side of the hill. There were some rough outbuildings at the back, and a strip of land for potatoes. A thin stream of smoke rose from the squat chimney. "The fire's on, and it won't take you long to boil that scrap of mutton. I suppose you can cook?" he said.

Mary looked him up and down. "Do you always make use of folk this way?" she said.

"I don't often have the chance," he told her. "But you may as well stop while you're here. I've done all my own cooking since my mother died, and there's not been a woman in the cottage since. Come in, won't you?"

She followed him in, bending her head as he did under the low door.

The room was small and square, half the size of the kitchen at Jamaica, with a great open fireplace in the corner. The floor was filthy and littered with rubbish; potato scrapings, cabbage stalks, and crumbs of bread. There were odds and ends scattered all over the room, and ashes from the turf fire covered everything. Mary looked about her in dismay.

"Don't you ever do any cleaning?" she asked him. "You've got this kitchen like a pigsty. You ought to be ashamed of yourself. Leave me that bucket of water and find me a broom. I'll not eat my dinner in a place like this."

She set to work at once, all her instincts of cleanliness and order aroused by the dirt and squalour. In half an hour she had the kitchen scrubbed clean as a pin, the stone floor wet and shining, and all the rubbish cleared away. She had found crockery in the cupboard, and a strip of tablecloth, with which she proceeded to lay the table, and meanwhile the mutton boiled in the saucepan on the fire, surrounded by potato and turnip.

The smell was good, and Jem came in at the door, sniffing the air like a hungry dog. "I shall have to keep a woman," he said. "I can see that. Will you leave your aunt and come and look after me?"

"You'd have to pay me too much," said Mary. "You'd never have money enough for what I'd ask."

"Women are always mean," he said, sitting down at the table. "What they do with their money I don't know, for they never spend it. My mother was just the same. She used to keep hers hidden in an old stocking and I never as much as saw the colour of it. Make haste with the dinner; I'm as empty as a worm."

"You're impatient, aren't you?" said Mary. "Not a word of thanks to me that's cooked it. Take your hands away — the plate's hot."

She put the steaming mutton down in front of him, and he smacked his lips. "They taught you something where you came from, anyway," he said. "I always say there's two things women ought to do by instinct, and cooking's one of 'em. Get me a jug of water, will you? You'll find the pitcher outside."

But Mary had filled a cup for him already, and she passed it to him in silence.

"We were all born here," said Jem, jerking his head to the ceiling, "up in the room overhead. But Joss and Matt were grown men when I was still a little lad, clinging to Mother's skirt. We never saw much of my father, but when he was home we knew it all right. I remember him throwing a knife at Mother once — it cut her above her eye, and the blood ran down her face. I was scared and ran and hid in that corner by the fire. Mother said nothing; she just bathed her eye in some water, and then she gave my father his supper. She was a brave woman, I'll say that for her, though she spoke little and she never gave us much to eat. She made a bit of a pet of me when I was small, on account of being the youngest, I suppose, and my brothers used to beat me when she wasn't looking. Not that they were as thick as you'd think — we were never much of a loving family — and I've seen Joss thrash Matt until he couldn't stand. Matt was a funny devil; he was quiet, more like my mother. He was drowned down in the marsh yonder. You could shout there until your lungs burst, no one would hear you except a bird or two and a stray pony. I've been nearly caught there myself in my time."

"How long has your mother been dead?" said Mary.

"Seven years this Christmas," he answered, helping himself to more boiled mutton. "What with my father hanged, and Matt drowned, and Joss gone off to America, and me growing up as wild as a hawk, she turned religious and used to pray here by the hour, calling on the Lord. I couldn't abide that, and I cleared off out of it. I shipped on a Padstow schooner for a time, but the sea didn't suit my stomach, and I came back home. I found Mother gone as thin as a skelton. 'You ought to eat more,' I told her, but she wouldn't listen to me, so I went off again, and stayed in Plymouth for a while, picking up a shilling or two in my own way. I came back here to have my Christmas dinner, and I found the place deserted and the door locked up. I was mad. I hadn't eaten for twenty-four hours. I went back to North Hill, and they told me my mother had died. She'd been buried three weeks. I might just as well have stayed in Plymouth for all the dinner I got that Christmas. There's a piece of cheese in the cupboard behind you. Will you eat the half of it? There's maggots in it, but they won't hurt you."

Mary shook her head, and she let him get up and reach for it himself.

"What's the matter?" he said. "You look like a sick cow. Has the mutton turned sour on you already?"

Mary watched him return to his seat and spread the hunk of dry cheese onto a scrap of stale bread. "It will be a good thing when there's not a Merlyn left in Cornwall," she said. "It's better to have disease in a country than a family like yours. You and your brother were born twisted and evil. Do you never think of what your mother must have suffered?"

Jem looked at her in surprise, the bread and cheese halfway to his mouth.

"Mother was all right," he said. "She never complained. She was used to us. Why, she married my father at sixteen; she never had time to suffer. Joss was born the year after, and then Matt. Her time was taken up in rearing them, and by the time they were out of her hands she had to start all over again with me. I was an afterthought, I was. Father got drunk at Launceston fair, after selling three cows that didn't belong to him. If it wasn't for that I wouldn't be sitting here talking to you now. Pass that jug."

Mary had finished. She got up and began to clear away the plates in silence.

"How's the landlord of Jamaica Inn?" said Jem, tilting back on his chair and watching her dip the plates in water.

"Drunk, like his father before him," said Mary shortly.

"That'll be the ruin of Joss," said his brother seriously. "He soaks himself insensible and lies like a log for days. One day he'll kill himself with it. The damned fool! How long has it lasted this time?"

"Five days."

"Oh, that's nothing to Joss. He'd lay there for a week if you let him. Then he'll come to, staggering on his feet like a newborn calf, with a mouth as black as Trewartha Marsh. When he's rid himself of his surplus liquid, and the rest of the drink has soaked into him — that's when you want to watch him; he's dangerous then. You look out for yourself."

"He'll not touch me; I'll take good care of that," said Mary. "He's got other things to worry him. There's plenty to keep him busy."

"Don't be mysterious, nodding to yourself with your mouth pursed up. Has anything been happening at Jamaica?"

"It depends how you look at it," said Mary, watching him over the plate she was wiping. "We had Mr. Bassat from North Hill last week."

Jem brought his chair to the ground with a crash. "The devil you did," he said. "And what had the squire to say to you?"

"Uncle Joss was from home," said Mary, "and Mr. Bassat insisted on coming into the inn and going through the rooms. He broke down the door at the end of the passage, he and his servant between them, but the room was empty. He seemed disappointed, and very surprised, and he rode away in a fit of temper. He asked after you, as it happened, and I told him I'd never set eyes on you."

Jem whistled tunelessly, his expression blank as Mary told her tale, but when she came to the end of her sentence, and the mention of his name, his eyes narrowed, and then he laughed. "Why did you lie to him?" he asked.

"It seemed less trouble at the time," said Mary. "If I'd thought longer, no doubt I'd have told him the truth. You've got nothing to hide, have you?"

"Nothing much, except that black pony you saw by the brook belongs to him," said Jem carelessly. "He was dapple-grey last week, and worth a small fortune to the squire, who bred him himself. I'll make a few pounds with him at Launceston if I'm lucky. Come down and have a look at him."

They went out into the sun, Mary wiping her hands on her apron, and she stood for a few moments at the door of the cottage while Jem went off to the horses. The cottage was built on the slope of the hill above the Withy Brook, whose course wound away in the valley and was lost in the further hills. Behind the house stretched a wide and level plain, rising to great tors on either hand, and this grassland — like a grazing place for cattle — with no boundary as far as the eye could reach except the craggy menace of Kilmar, must be the strip of country known as Twelve Men's Moor.

Mary pictured Joss Merlyn running out of the doorway here as a child, his mat of hair falling over his eyes in a fringe, with the gaunt, lonely figure of his mother standing behind him, her arms folded, watching him with a question in her eyes. A world of sorrow and silence, anger and bitterness too, must have passed beneath the roof of this small cottage.

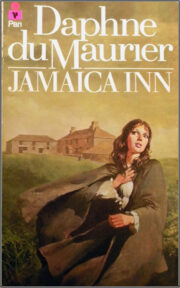

"Jamaica Inn" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Jamaica Inn". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Jamaica Inn" друзьям в соцсетях.