Firmly the doctor pushed the little gaping crowd away from the door. Together he and the man Searle lifted the still figure from the floor and carried her upstairs to the bedroom.

"It's a stroke," said the doctor, "but she's breathing; her pulse is steady. This is what I've been afraid of — that she'd snap suddenly, like this. Why it's come just now after all these years is known only to the Lord and herself. You must prove yourself your parents' child now, Mary, and help her through this. You are the only one who can."

For six long months or more Mary nursed her mother in this her first and last illness, but with all the care she and the doctor gave her it was not the widow's will to recover. She had no wish to fight for her life.

It was as though she longed for release and prayed silently that it would come quickly. She said to Mary, "I don't want you to struggle as I have done. It's a breaking of the body and of the spirit. There's no call for you to stay on in Helford after I am gone. It's best for you to go to your aunt Patience up to Bodmin."

There was no use in Mary telling her mother that she would not die. It was fixed there in her mind, and there was no fighting it.

"I haven't any wish to leave the farm, Mother," she said. "I was born here and my father before me, and you were a Helford woman. This is where the Yellans belong to be. I'm not afraid of being poor, and the farm falling away. You worked here for seventeen years alone, so why shouldn't I do the same? I'm strong; I can do the work of a man; you know that."

"It's no life for a girl," said her mother. "I did it all these years because of your father, and because of you. Working for someone keeps a woman calm and contented, but it's another thing when you work for yourself. There's no heart in it then."

"I'd be no use in a town," said Mary. "I've never known anything but this life by the river, and I don't want to. Going into Helston is town enough for me. I'm best here, with the few chickens that's left to us, and the green stuff in the garden, and the old pig, and a bit of a boat on the river. What would I do up to Bodmin with my Aunt Patience?"

"A girl can't live alone, Mary, without she goes queer in the head, or comes to evil. It's either one or the other. Have you forgotten poor Sue, who walked the churchyard at midnight with the full moon, and called upon the lover she had never had? And there was one maid, before you were born, left an orphan at sixteen. She ran away at Falmouth and went with the sailors.

"I'd not rest in my grave, nor your father neither, if we didn't leave you safe. You'll like your Aunt Patience; she was always a great one for games and laughing, with a heart as large as life. You remember when she came here, twelve years back? She had ribbons in her bonnet and a silk petticoat. There was a fellow working at Trelowarren had an eye to her, but she thought herself too good for him."

Yes, Mary remembered Aunt Patience, with her curled fringe and large blue eyes, and how she laughed and chatted, and how she picked up her skirts and tiptoed through the mud in the yard. She was as pretty as a fairy.

"What sort of a man your Uncle Joshua is I cannot say," said her mother, "for I've never set eyes on him nor known anyone what has. But when your aunt married him ten years ago last Michaelmas she wrote a pack of giddy nonsense you'd expect a girl to write, and not a woman over thirty."

"They'd think me rough," said Mary slowly. "I haven't the pretty manners they'd expect. We wouldn't have much to say to one another."

"They'll love you for yourself and not for any airs and graces. I want you to promise me this, child, that when I'm gone you'll write to your Aunt Patience and tell her that it was my last and dearest wish that you should go to her."

"I promise," said Mary, but her heart was heavy and distressed at the thought of a future so insecure and changed, with all that she had known and loved gone from her, and not even the comfort of familiar trodden ground to help her through the days when they came.

Daily her mother weakened; daily the life ebbed from her. She lingered through harvest-time, and through the fruit picking, and through the first falling of the leaves. But when the mists came in the morning, and the frosts settled on the ground, and the swollen river ran in flood to meet the boisterous sea, and the waves thundered and broke on the little beaches of Helford, the widow turned restlessly in her bed, plucking at the sheets. She called Mary by her dead husband's name, and spoke of things that were gone and of people Mary had never known. For three days she lived in a little world of her own, and on the fourth day she died.

One by one Mary saw the things she had loved and understood pass into other hands. The livestock went at Helston market. The furniture was bought by neighbours, stick by stick. A man from Coverack took a fancy to the house and purchased it; with pipe in mouth he straddled the yard and pointed out the changes he would make, the trees he would cut down to clear his view; while Mary watched him in dumb loathing from her window as she packed her small belongings in her father's trunk.

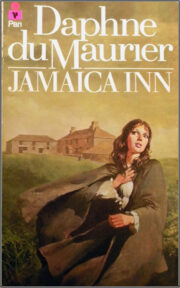

This stranger from Coverack made her an interloper in her own home; she could see from his eye he wanted her to be gone, and she had no other thought now but to be away and out of it all, and her back turned for ever. Once more she read the letter from her aunt, written in a cramped hand, on plain paper. The writer said she was shocked at the blow that had befallen her niece; that she had had no idea her sister was ill, it was so many years now since she had been to Helford. And she went on: "There have been changes with us you would not know. I no longer live in Bodmin. but nearly twelve miles outside, on the road to Launceston. It's a wild and lonely spot, and if you were to come to us I should be glad of your company, wintertime. I have asked your uncle, and he does not object, he says, if you are quiet-spoken and not a talker, and will give help when needed. He cannot give you money, or feed you for nothing, as you will understand. He will expect your help in the bar, in return for your board and lodging. You see, your uncle is the landlord of Jamaica Inn."

Mary folded the letter and put it in her trunk. It was a strange message of welcome from the smiling Aunt Patience she remembered.

A cold, empty letter, giving no word of comfort, and admitting nothing, except that her niece must not ask for money. Aunt Patience, with her silk petticoat and delicate ways, the wife of an innkeeper! Mary decided that this was something her mother had not known. The letter was very different from the one penned by a happy bride ten years ago.

However, Mary had promised, and there was no returning on her word. Her home was sold; there was no place for her here. Whatever her welcome should be, her aunt was her own mother's sister, and that was the one thing to remember. The old life lay behind — the dear familiar farm and the shining Helford waters. Before her lay the future — and Jamaica Inn.

And so it was that Mary Yellan found herself northward bound from Helston in the creaking, swaying coach, through Truro town, at the head of the Fal, with its many roofs and spires, its broad cobbled streets, the blue sky overhead still speaking of the south, the people at the doors smiling, and waving as the coach rattled past. But when Truro lay behind in the valley, the sky came overcast, and the country on either side of the highroad grew rough and untilled. Villages were scattered now, and there were few smiling faces at the cottage doors. Trees were sparse; hedges there were none. Then the wind blew, and the rain came with the wind. And so the coach rumbled into Bodmin, grey and forbidding like the hills that cradled it, and one by one the passengers gathered up their things in preparation for departure — all save Mary, who sat still in her corner. The driver, his face a stream of rain, looked in at the window.

"Are you going on to Launceston?" he said. "It'll be a wild drive tonight across the moors. You can stay in Bodmin, you know, and go on by coach in the morning. There'll be none in this coach going on but you."

"My friends will be expecting me," said Mary. "I'm not afraid of the drive. And I don't want to go as far as Launceston; will you please put me down at Jamaica Inn?"

The man looked at her curiously. "Jamaica Inn?" he said. "What would you be doing at Jamaica Inn? That's no place for a girl. You must have made a mistake, surely." He stared at her hard, not believing her.

"Oh, I've heard it's lonely enough," said Mary, "but I don't belong to a town anyway. It's quiet on Helford River, winter and summer, where I come from, and I never felt lonely there."

"I never said nothing about loneliness," answered the man. "Maybe you don't understand, being a stranger up here. It's not the twenty-odd mile of moor I'm thinking of, though that'd scare most women. Here, wait a minute." He called over his shoulder to a woman who stood in the doorway of the Royal, lighting the lamp above the porch, for it was already dusk.

"Missus," he said, "come here an' reason with this young girl. I was told she was for Launceston, but she's asked me to put her down at Jamaica."

The woman came down the steps and peered into the coach.

"It's a wild, rough place up there," she said, "and if it's work you are looking for, you won't find it on the farms. They don't like strangers on the moors. You'd do better down here in Bodmin."

Mary smiled at her. "I shall be all right," she said. "I'm going to relatives. My uncle is landlord of Jamaica Inn."

There was a long silence. In the grey light of the coach Mary could see that the woman and the man were staring at her. She felt chilled suddenly, anxious; she wanted some word of reassurance from the woman, but it did not come. Then the woman drew back from the window. "I'm sorry," she said slowly. "It's none of my business, of course. Good night."

"Jamaica Inn" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Jamaica Inn". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Jamaica Inn" друзьям в соцсетях.