The ground was now soggy beneath her feet, for here the early frost had thawed and turned to water, and the whole of the low-lying plain before her was soft and yellow from the winter rains. The damp oozed into her shoes with cold and clammy certainty, and the hem of her skirt was bespattered with bog and torn in places. Lifting it up higher, and hitching it round her waist with the ribbon from her hair, Mary plunged on in trail of her uncle, but he had already traversed the worst of the low ground with uncanny quickness born of long custom, and she could just make out his figure amongst the black heather and the great boulders at the foot of Brown Willy. Then he was hidden by a jutting crag of granite, and she saw him no more.

It was impossible to discover the path he had taken across the bog; he had been over and gone in a flash, and Mary followed as best she could, floundering at every step. She was a fool to attempt it, she knew that, but a sort of stubborn stupidity made her continue. Ignorant of the whereabouts of the track that had carried her uncle dryshod over the bog, Mary had sense enough to make a wide circuit to avoid the treacherous ground, and, by going quite two miles in the wrong direction, she was able to cross in comparative safety. She was now hopelessly left, without a prospect of finding her uncle again.

Nevertheless she set herself to climb Brown Willy, slipping and stumbling amongst the wet moss and the stones, scrambling up the great peaks of jagged granite that frustrated her at every turn, while now and again a hill sheep, startled by the sound of her, ran out from behind a boulder to gaze at her and stamp his feet. Clouds were bearing up from the west, casting changing shadows on the plains beneath, and the sun went in behind them.

It was very silent on the hills. Once a raven rose up at her feet and screamed; he went away flapping his great black wings, swooping to the earth below with harsh protesting cries.

When Mary reached the summit of the hill the evening clouds were banked high above her head and the world was grey. The distant horizon was blotted out in the gathering dusk, and thin white mist rose from the moors beneath. Approaching the tor from its steepest and most difficult side, as she had done, she had wasted nearly an hour out of her time, and darkness would soon be upon her. Her escapade had been to little purpose, for as far as her eyes could see there was no living thing within their range.

Joss Merlyn had long vanished; and for all she knew he might not have climbed the tor at all, but skirted its base amongst the rough heather and the smaller stones, and then made his way alone and unobserved, east or west as his business took him, to be swallowed up in the folds of the further hills.

Mary would never find him now. The best course was to descend the tor by the shortest possible way and in the speediest fashion, otherwise she would be faced with the prospect of a winter's night upon the moors, with dead-black heather for a pillow and no other shelter but frowning crags of granite. She knew herself now for a fool to have ventured so far on a December afternoon, for experience had proved to her that there were no long twilights on Bodmin Moor. When darkness came it was swift and sudden, without warning, and with an immediate blotting out of the sun. The mists were dangerous too, rising in a cloud from the damp ground and closing in about the marshes like a white barrier.

Discouraged and depressed, and all excitement gone from her, Mary scrambled down the steep face of the tor, one eye on the marshes below and the other for the darkness that threatened to overtake her. Directly below her there was a pool or well, said to be the source of the river Fowey that ran ultimately to the sea, and this must be avoided at all costs, for the ground around was boggy and treacherous and the well itself of an unknown depth.

She bore to her left to avoid it, but by the time she had reached the level of the plain below, with Brown Willy safely descended and lifting his mighty head in lonely splendour behind her, the mist and the darkness had settled on the moors, and all sense of direction was now lost to her.

Whatever happened she must keep her head, and not give way to her growing sense of panic. Apart from the mist the evening was fine, and not too cold, and there was no reason why she should not hit upon some track that would lead ultimately to habitation.

There was no danger from the marshes if she kept to the high ground, so, trussing up her skirt again and wrapping her shawl firmly round her shoulders. Mary walked steadily before her, feeling the ground with some care when in doubt, and avoiding those tufts of grass that felt soft and yielding to her feet. That the direction she was taking was unknown to her was obvious in the first few miles, for her way was barred suddenly by a stream that she had not passed on the outward journey. To travel by its side would only lead her once more to the low-lying ground and the marshes, so she plunged through it recklessly, soaking herself above the knee. Wet shoes and stockings did not worry her; she counted herself fortunate that the stream had not been deeper, which would have meant swimming for it, and a chilled body into the bargain. The ground now seemed to rise in front of her, which was all to the good, as the going was firm, and she struck boldly across the high downland for what seemed to be an interminable distance, coming at length to a rough track bearing ahead and slightly to the right. This at any rate had served for a cart's wheels at one time or other, and where a cart could go Mary could follow. The worst was past; and now that her real anxiety had gone she felt weak and desperately tired.

Her limbs were heavy, dragging things that scarcely belonged to her, and her eyes felt sunken away back in her head. She plodded on, her chin low and her hands at her side, thinking that the tall grey chimneys of Jamaica Inn would be, for the first time perhaps in their existence, a welcome and consoling sight. The track broadened now and was crossed in turn by another running left and right, and Mary stood uncertainly for a few moments, wondering which to take. It was then that she heard the sound of a horse, blowing as though he had been ridden hard, coming out of the darkness to the left of her.

His hoofs made a dull thudding sound on the turf. Mary waited in the middle of the track, her nerves ajingle with the suddenness of the approach, and presently the horse appeared out of the mist in front of her, a rider on his back, the pair of ghostly figures lacking reality in the dim light. The horseman swerved as he saw Mary and pulled up his horse to avoid her.

"Hullo," he cried, "who's there? Is anyone in trouble?"

He peered down at her from his saddle and exclaimed in surprise. "A woman!" he said. "What in the world are you doing out here?"

Mary seized hold of his rein and quieted the restive horse.

"Can you put me on the road?" she asked. "I'm miles from home and hopelessly lost."

"Steady there," he said to the horse. "Stand still will you? Where have you come from? Of course I will help you if I can."

His voice was low and gentle, and Mary could see he must be a person of quality.

"I live at Jamaica Inn," she said, and no sooner were the words out of her mouth than she regretted them. He would not help her now, of course; the very name was enough to make him whip on his horse and leave her to find her own way as best she could. She was a fool to have spoken.

For a moment the man was silent, which was only what she expected, but when he spoke again his voice had not changed, but was quiet and gentle as before.

"Jamaica Inn," he said. "You've come a long way out of your road, I'm afraid. You must have been walking in the opposite direction. You're the other side of Hendra Downs here, you know."

"That means nothing to me," she told him. "I've never been this way before; it was very stupid of me to venture so far on a winter's afternoon. I'd be grateful if you could show me to the right path, and, once on the highroad, it won't take me long to get home."

He considered her for a moment, and then he swung himself off the saddle to the ground. "You're exhausted," he said, "you aren't fit to walk another step; and, what's more, I'm not going to let you. We are not far from the village, and you shall ride there. Will you give me your foot, and I'll help you mount." In a minute she was up in the saddle, and he stood below her, the bridle in his hand. "That's better, isn't it?" he said. "You must have had a long and uncomfortable walk on the moors. Your shoes are soaking wet, and so is the hem of your gown. You shall come home with me, and dry those things and rest awhile, and have some supper, before I take you back myself to Jamaica Inn." He spoke with such solicitude, and yet with such calm authority, that Mary sighed with relief, throwing all responsibility aside for the time being, content to trust herself in his keeping. He arranged the reins to her satisfaction, and she saw his eyes for the first time looking up at her from beneath the brim of his hat. They were strange eyes, transparent like glass, and so pale in colour that they seemed near to white; a freak of nature she had never known before. They fastened upon her, and searched her, as though her very thoughts could not be hidden, and Mary felt herself relax before him and give way; and she did not mind. His hair was white, too, under his black shovel hat, and Mary stared back at him in some perplexity, for his face was unlined, and his voice was not that of an elderly man.

Then, with a little rush of embarrassment, she understood the reason for his abnormality, and she turned away her eyes. He was an albino.

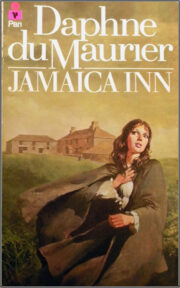

"Jamaica Inn" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Jamaica Inn". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Jamaica Inn" друзьям в соцсетях.