The man appeared at the stable door, leading the two horses behind him.

"Now listen to me," said Mr. Bassat, pointing his crop at Mary. "This aunt of yours may have lost her tongue, and her senses with them, but you can understand plain English, I hope. Do you mean to tell me you know nothing of your uncle's business? Does nobody ever call here, by day or by night?"

Mary looked him straight in the eyes. "I've never seen anyone," she said.

"Have you ever looked into that barred room before today?"

"No, never in my life."

"Have you any idea why he should keep it locked up?"

"No, none at all."

"Have you ever heard wheels in the yard by night?"

"I'm a very heavy sleeper. Nothing ever wakes me."

"Where does your uncle go when he's away from home?"

"I don't know."

"Don't you think yourself it's very peculiar to keep an inn on the King's highway, and then bolt and bar your house to every passer-by?"

"My uncle is a very peculiar man."

"He is indeed. In fact, he's so damned peculiar that half the people in the countryside won't sleep easy in their beds until he's been hanged, like his father before him. You can tell him that from me."

"I will, Mr. Bassat."

"Aren't you afraid, living up here, without sound or sight of a neighbour, and only this half-crazy woman for companion?"

"The time passes."

"You've got a close tongue, haven't you, young woman? Well, I don't envy you your relatives. I'd rather see any daughter of mine in her grave than living at Jamaica Inn with a man like Joss Merlyn."

He turned away and climbed onto his horse, gathering the reins in his hands. "One other thing," he called from his saddle. "Have you seen anything of your uncle's younger brother, Jem Merlyn, of Trewartha?"

"No," said Mary steadily; "he never comes here."

"Oh, he doesn't? Well, that's all I want from you this morning. Good day to you both." And away they clattered from the yard, and so down the road and to the brow of the further hill.

Aunt Patience had already preceded Mary to the kitchen and was sitting on a chair in a state of collapse.

"Oh, pull yourself together," said Mary wearily. "Mr. Bassat has gone, none the wiser for his visit, and as cross as two sticks because of it. If he'd found the room reeking of brandy, then there would be something to cry about. As it is, you and Uncle Joss have scraped out of it very well."

She poured herself out a tumbler of water and drank it at one breath. Mary was in a fair way to losing her temper. She had lied to save her uncle's skin, when every inch of her longed to proclaim his guilt. She had looked into the barred room, and its emptiness had hardly surprised her when she remembered the visitation of the waggons a few nights back; but to have been faced with that loathsome length of rope, which she recognised immediately as the one she had seen hanging from the beam, was almost more than she could bear. And because of her aunt she had to stand still and say nothing. It was damnable; there was no other word for it. Well, she was committed now, and there was no going back. For better, for worse, she had become one of the company at Jamaica Inn. As she drank down her second glass of water she reflected cynically that in the end she would probably hang beside her uncle. Not only had she lied to save him, she thought with rising anger, but she had lied to help his brother, Jem. Jem Merlyn owed her thanks as well. Why she had lied about him she did not know. He would probably never find out anyway, and, if he did, he would take it for granted.

Aunt Patience was still moaning and whimpering before the fire, and Mary was in no mood to comfort her. She felt she had done enough for her family for one day, and her nerves were on edge with the whole business. If she stayed in the kitchen a moment longer she would scream with irritation. She went back to the washtub in the patch of garden by the chicken run and plunged her hands savagely into the grey soapy water that was now stone-cold.

Joss Merlyn returned just before noon. Mary heard him step into the kitchen from the front of the house, and he was met at once with a babble of words from his wife. Mary stayed where she was by the washtub; she was determined to let Aunt Patience explain things in her own way, and, if he called to her for confirmation, there was time enough to go indoors.

She could hear nothing of what passed between them, but the voice of her aunt sounded shrill and high, and now and again her uncle interposed a question sharply. In a little while he beckoned Mary from the window, and she went inside. He was standing on the hearth, his legs straddled wide and his face as black as thunder.

"Come on!" he shouted. "Out with it. What's your side of the story? I get nothing but a string of words from your aunt; a magpie makes more sense than she. What in hell's been going on here? That's what I want to know."

Mary told him calmly, in a few well-chosen words, what had taken place during the morning. She omitted nothing — except the squire's question about his brother — and ended with Mr. Bassat's own words — that people would not sleep easy in their beds until Joss Merlyn was hanged, like his father before him.

The landlord listened in silence, and, when she had finished, he crashed his fist down on the kitchen table and swore, kicking one of the chairs to the other side of the room.

"The damned skulking bastard!" he roared. "He'd no more right to walk into my house than any other man. His talk of a magistrate's warrant was all bluff, you blithering fools; there's no such thing. By God, if I'd been here, I'd have sent him back to North Hill so as his own wife would never recognise him, and, if she did, she'd have no use for him again. Damn and blast his eyes! I'll teach Mr. Bassat who's got the run of this country, and have him sniffing round my legs, what's more. Scared you, did he? I'll burn his house round his ears if he plays his tricks again."

Joss Merlyn shouted at the top of his voice, and the noise was deafening. Mary did not fear him like this; the whole thing was bluster and show; it was when he lowered his voice and whispered that she knew him to be deadly. For all his thunder he was frightened; she could see that; and his confidence was rudely shaken.

"Get me something to eat," he said. "I must go out again, and there's no time to lose. Stop that yawling, Patience, or I'll smash your face in. You've done well today, Mary, and I'll not forget it."

His niece looked him in the eyes. "You don't think I did it for you, do you?" she said.

"I don't care a damn why you did it, the result's the same," he answered. "Not that a blind fool like Bassat would find anything anyway; he was born with his head in the wrong place. Cut me a hunk of bread, and quit talking, and sit down at the bottom of the table where you belong to be."

The two women took their seats in silence, and the meal passed without further disturbance. As soon as he had finished, the landlord rose to his feet and, without another word to either of them, made his way to the stable. Mary expected to hear him lead his pony out once more and ride off down the road, but in a minute or two he was back again, and, passing through the kitchen, he went down to the end of the garden and climbed the stile in the field. Mary watched him strike across the moor and ascend the steep incline that led to Tolborough Tor and Codda. For a moment she hesitated, debating the wisdom of the sudden plan in her head, and then the sound of her aunt's footsteps overhead appeared to decide her. She waited until she heard the door of the bedroom close, and then, throwing off her apron and seizing her thick shawl from its peg on the wall, she ran down the field after her uncle. When she reached the bottom she crouched beside the stone wall until his figure crossed the skyline and disappeared, and then she leapt up again and followed in his track, picking her way amongst the rough grass and stones. It was a mad and senseless venture, no doubt, but her mood was a reckless one, and she needed an outlet for it after her silence of the morning.

Her idea was to keep Joss Merlyn in view, remaining of course unseen, and in this way perhaps she would learn something of his secret mission. She had no doubt that the squire's visit to Jamaica had altered the landlord's plans, and that this sudden departure on foot across the heart of the West Moor was connected with it. It was not yet half past one, and an ideal afternoon for walking. Mary, with her stout shoes and short skirt to her ankles, cared little for the rough ground. It was dry enough underfoot — the frost had hardened the surface — and, accustomed as she was to the wet shingle of the Helford shore and the thick mud on the farmyard, this scramble over the moor seemed easy enough. Her earlier rambles had taught her some wisdom, and she kept to the high ground as much as possible, following as best she could the tracks taken by her uncle.

Her task was a difficult one, and after a few miles she began to realise it. She was forced to keep a good length between them in order to remain unseen, and the landlord walked at such a pace, and took such tremendous strides, that before long Mary saw she would be left behind. Codda Tor was passed, and he turned west now towards the low ground at the foot of Brown Willy, looking, for all his height, like a little black dot against the brown stretch of moor.

The prospect of climbing some thirteen hundred feet came as something of a shock to Mary, and she paused for a moment and wiped her streaming face. She let down her hair, for greater comfort, and let it blow about her face. Why the landlord of Jamaica Inn thought it necessary to climb the highest point on Bodmin Moor on a December afternoon she could not tell, but, having come so far, she was determined to have some satisfaction for her pains, and she set off again at a sharper pace.

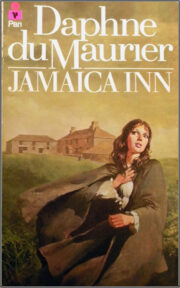

"Jamaica Inn" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Jamaica Inn". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Jamaica Inn" друзьям в соцсетях.