‘They are taking a risk,’ suggested Caroline.

‘Well, they have to take a risk— but a small one. They’re banking on the impossibility of having a public trial in which the Regent would show up in none too good a light. Moreover, all those spies of theirs might have been ready to swear before the Lords Commissioners but would they be prepared to do so in a court of law? Consider the penalties of perjury, dear Madam. No, this is good, there will be no trial. And they don’t deceive people in the know.’

He was right. News came that the Duke of Sussex had dismissed Sir John Douglas from his service. This was taken as a vindication of Caroline and there were bonfires in the streets and the effigies which were burned were those of Sir John and Lady Douglas.

The Duchess of Brunswick died at the time. Caroline was saddened, but her mother’s behaviour had not been exactly endearing. The Prince, on attaining the Regency, had offered her an apartment in Carlton House. Caroline guessed that this was to discountenance her; and the old lady had been eager to accept and would have done so had she not been prevailed upon by her son to refrain from doing so. So she had declined and continued to hold court in her dark and gloomy old house in New Street, Spring Gardens; but she did seem to take a delight in the humiliations heaped on her daughter, while she declared her dear nephew, the Prince Regent, was always charming to her.

Caroline, was understandably, concerned with the fate of her mother’s faithful lady-in-waiting, Lady Finiater, who on the death of the Duchess was left in very dire straits, and endeavoured to get her pension of five hundred a year.

Caroline was beginning to see that the Regent was too powerful for her. There would always be trouble, and as he was almost the King, she had little chance against him.

Charlotte was to be betrothed to the Prince of Orange, a match which the young Princess viewed with some distaste; and Caroline longed to be with her, to condole with her, to stop her making an unhappy marriage as she had.

Bat Charlotte had spirit and her father was a little afraid of her on account of that great affection she inspired wherever she went and the greater it became, the more he realized that quarrel between them could be disastrous to his own standing with the people.

He groaned and cursed his wife and daughter. Never was it man such a lover of the female sex, and never was a father and husband so plagued by them.

He blamed everything on to Caroline; he hated her; he could not bear to think of her. The manner in which she behaved disgusted him. She was vulgar; she had no sense of decorum; she was everything that he was not; and to think that she was the mother of the heiress to the throne enraged him.

When the Czar of Russia visited England he was determined to keep Caroline out of his sight for he could not endure the thought of the Czar’s seeing her and knowing that she was his wife.

When Caroline heard that there was to be a State visit to the Opera, she mischievously decided to discountenance the Regent.

‘They may ban me from the drawing rooms but they can’t prevent my going to the Opera,’ she announced triumphantly.

And while she was dressed for the occasion she grumbled to Lady Charlotte and her women about the manner in which she had been excluded from the Queen’s drawing room.

‘The Regent has said he does not wish to see you. And how can I ban the Regent from my drawing room?’ she mimicked the Queen. ‘ I fear in the circumstances I cannot invite you to attend. The old Begum! We have more fun in Montague House in five minutes than they do in a year in the old drawing rooms.’

She laughed gleefully, and gazed in delight at her reflection while Lady Charlotte shuddered inwardly. Could she really be contemplating visiting the Opera like that? She wore black velvet and on her head had set an elaborately curled wig so black that her face heavily daubed with white lead and rouge made a startling contrast.

‘Come on,’ she cried. ‘Smack it on. I want to be noticed tonight.’

Her large bosom was generously displayed and she called Willikin to comment on her appearance. He threw his arms about her neck and she gave him several smacking kisses and was clearly contemplating taking him with her.

Oh God, prayed Lady Charlotte, don’t let her be as foolish as that. Fortunately she changed her mind in time.

At the Opera the National Anthem was being played when she arrived. The Prince Regent was standing to attention in his box— on one side of him the Czar of Russia, on the other the King of Prussia.

The anthem over, the audience seated itself and then someone in the stalls noticed her.

‘The Princess of Wales!’ the cry went up and the people began to cheer. Here was a situation more interesting than the Opera could hope to be. The Princess and the Prince in the house together.

The Czar was looking interested.

‘What a handsome fellow,’ whispered Caroline excitedly.

‘Madam,’ said Lady Charlotte, ‘the people expect you to rise and acknowledge their cheers.’

‘Oh no,’ she said audibly, ‘Punch’s wife is nobody when Punch is there. I know my business better than to take the morsel out of my husband’s mouth.’

The applause continued.

And the Prince Regent with that elegance and savoir-faire which Caroline could never hope to understand, let alone emulate, rose turning to face her and gave the house and Caroline the benefit of that elegant bow which was the admiration of all who beheld it.

It was an evening of triumph for Caroline and of exasperating humility for the Prince. For when the Opera was over she went out to the carriage and found a crowd waiting for her.

They were also waiting for the Prince Regent. ‘Where’s your wife, George?’ they asked mockingly. This was particularly infuriating when he was in the company of visiting royalty.

As for Caroline it was: ‘Long live the Princess. God bless the innocent.’

They crowded round her carriage; they insisted on shaking hands with her.

Nothing loath she opened the door and took their hands in her affable friendly way. They cheered her lustily. She was the heroine of the evening.

One cried: ‘Shall we burn down Carlton House? You only have to say the word.’

‘No, no,’ she cried. ‘Just let me pass now and go home and sleep peacefully.

And God bless you.’

‘God bless you,’ they cried.

It was certainly a triumph.

But she soon realized the emptiness of such triumphs. The Czar had been impressed or amused by the evening at the Opera and he sent a note to Caroline asking permission to call on her.

How delightedly she gave it! ‘We must have a banquet. My word, this will put his little nose out of joint. We’ll have such a spectacle as to compete with anything he’s ever had at Carlton House.’

That was a wild exaggeration, of course, but it delighted her to think that in spite of her in-laws she was to receive the royal visitor.

She set her cooks to work; she sat with her women while long hours were spent on her toilette. She insisted that the rouge and white lead should not be spared.

‘That’s what he liked last time. Give him lots of it.’

But when she was ready she waited in vain; for the royal visitor did not appear.

Doubtless he had been made to realize by his advisers that he could not in a foreign country visit a Princess who was ignored by the Prince Regent.

Caroline took off her wig and threw it into the air. ‘Well, that’s that, my angels.’

She became very melancholy.

‘I don’t know why I stay in this country to be treated in this way. What’s to stop my leaving it? I can’t see anything to stand in the way.’

‘There’s war on the Continent,’ pointed out Lady Charlotte.

‘So there is. But if there was not, do you know I think I should go away. It would be the best for everyone, including myself. I’d take Willie with me and some of you dear friends.’

‘What of the Princess Charlotte?’

‘Ah, my Charlotte! But you know she is in constant conflict with her father and a great deal of that trouble is through her loyalty to me. So perhaps it would even be better for her.’

She sighed. She was certainly in one of her moods of, deepest depression.

She left the house she had taken in Connaught Place for Blackheath. There, she said, she could brood on her troubles, for she was becoming increasingly aware that she would have to take some action— though what she was unsure.

Montague House was always a comfort. There she had had her happiest times.

She decided she would send for the Sapios and they should soothe her with their music. It would comfort her considerably and perhaps provide her with the inspiration she needed.

Lady Charlotte came hurrying in with a look of consternation. ‘Your Highness, there is a carriage at the door. You are implored to leave without delay for Connaught House.’

‘This is too much. I refuse—’

‘Madam, the Princess Charlotte is there. She has run away— to you.’

‘Get my cape at once,’ cried Caroline; and in a few minutes she was on the way to Connaught House.

There she found Brougham, some of Charlotte’s ladies, the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Lord Chancellor Eldon, the Duke of York and the Duke of Sussex. And in the midst of this gathering a very defiant Charlotte who when she saw her mother ran to her and threw herself into her arms.

‘It’s no use,’ she said. ‘I shall not go back. I am going to live with my mother.

I have chosen.’

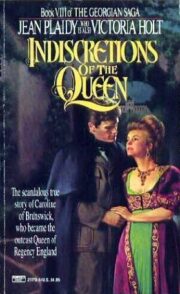

"Indiscretions of the Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Indiscretions of the Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Indiscretions of the Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.