It had happened so quickly and seemed so pointless.

When the murderer was caught he proved to be a madman named John Bellingham who had recently come from Russia where he had been arrested for some small misdemeanour. He had appealed to the English ambassador there and as nothing had been done to help him, he blamed the government. His revenge was to shoot the Prime Minister.

About a fortnight after the death of Perceval, the London crowds turned out in their thousands to see Bellingham hanged. It was quite a spectacle.

Caroline was desolate, for she knew she had lost a good friend.

After the assassination of Perceval, Lords Wellesley and Moira had attempted to form a government and when they failed to do so, the Earl of Liverpool became Prime Minister. Caroline very quickly became aware of the change in her fortunes.

One of her greatest compensations was the affection her daughter felt for her, and the weekly visits to Charlotte were the highlights of her life. Charlotte was now a very forthright sixteen, and being aware that she was the heiress to the throne was not inclined to be forced to anything that she did not want. She was a great favourite with the people and everywhere she went she was cheered.

How different it was with the Regent! He was met by sullen silences and the occasional booing. The people took up the case of Charlotte and Caroline, and the general opinion was that the Regent was not only a bad husband but a cruel father. They laughed at his elegance, and his corpulence was exaggerated in all the cartoons. If he had remained faithful to Maria Fitzherbert they would have had some respect for him. But he was constantly in the company of Lady Hertford whose frigid manners assured her an unpopularity to match his own.

It was irritating to him to be given continual proof of the people’s affection for his wife and daughter; and in a petulant mood he ordered that Caroline and Charlotte, instead of meeting once a week, should meet only once a fortnight.

Caroline was furious.

‘Oh, what a wicked man he is! What harm are we doing him by meeting? My little Charlotte will be upset, too. Does he think I will endure this? He will see.’

Charlotte was at Windsor and the Queen and the Princesses were also in residence, so Caroline wrote to the Queen telling her that she intended visiting Windsor to see her daughter.

A cool note from Her Majesty informed her that it was the Regent’s wish that the Princess Charlotte’s lessons should not be disturbed; therefore it would not be possible for Caroline to see her if she came to Windsor.

This threw Caroline into a violent rage. ‘Does the old Begum think that she is going to keep me from my daughter? Charlotte hates her— always has! Why I remember when she was little her saying: The two things I hate are apple-pie and Grandmamma. That shows, does it not? And she has not changed. She still hates apple-pie and Grandmamma. And this is the woman who will keep me from her. I am going to Windsor, old Begum or not.’

Lady Charlotte asked timidly if Her Highness thought that wise in view of the Queen’s letter.

‘Dear Lady Charlotte, I am not concerned with the wisdom!’ Caroline cried.

So to Windsor she went. But the visit was not a success. The Queen received her coldly.

‘I fear,’ she said, ‘that you cannot see the Princess Charlotte. We have to obey the Regent’s orders, do we not?’

‘I am going to see her.’

The Queen looked surprised. ‘Perhaps I have not made it clear that these are the Regent’s orders.’

Caroline cried: ‘I’ll find her. I’ll see her. You’ll not keep me from my own daughter.’

The Queen looked horrified. What could one do with a woman who was so ignorant of the respect and homage due to the Crown?

‘I beg of you to leave, she said coldly. ‘I am sure you do not wish me to have you taken away.’

And something in the coldness of her manner made Caroline realize how powerless she was. The Queen could call her servants, or even the guards to have her forcibly removed. There was nothing she could do, but return fuming to Blackheath.

As soon as she returned to Blackheath she sat down and wrote a letter: Sir, It is with great reluctance that I presume to intrude upon Your Royal Highness and to solicit your attention to matters which may, at first, appear rather of a personal than of a public nature— There is a point beyond which a guiltless woman cannot with safety carry her forbearance. If her honour is invaded, the defense of her renutation is no longer a matter of choice; and it signifies not whether the attack be made openly, manfully and directly— or by secret insinuation, and by holding such conduct towards her as countenances all the suspicions that malice can suggest— I presume, sir, to suggest to Your Royal Highness, every succeeding month that the separation, which every succeeding month is making wider, of the mother and the daughter, is equally injurious to my character and to her education. I say nothing of the deep wounds which so cruel an arrangement inflicts on my feelings.’ She went on to write of the implications of such a decree but she signed herself: Your Royal Highness’s most devoted and most affectionate Consort, Cousin and Subject, Caroline Amelia. This letter she had delivered to the Prime Minister, Lord Liverpool, with the request that he should hand it to the Prince Regent. The Prime Minister returned the letter unopened the following day with a covering note.

His Royal Highness has stated that he will receive no communication from Your Highness and sees no reason why he should change that decision. ‘Very well,’ cried Caroline, ‘I will publish this letter that the people may read it.’

Shortly after it appeared in the Morning Chronicle.

This naturally had its repercussions in the fury of the people against the Regent and their increased sympathy towards Caroline. But this, the Regent ignored, and Caroline received a letter from Lord Liverpool in which he said that in view of the publication of the letter, the Prince Regent had commanded that her next meeting with the Princess Charlotte should be cancelled.

But the mood of the people and the truculent attitude of Caroline forced the Regent to a decision. He called together a committee to decide what the relationship between the Princess of Wales and her daughter should be; and he asked that the papers which were accumulated during the Douglas case be studied again in the hope of proving to the people of England that Caroline was no fit companion for the heiress to the throne.

Caroline was not without friends and now that she had lost Perceval she found two ardent supporters in Baron Brougham and Vaux, a distinguished lawyer and politician, and Samuel Whitbread, the Member for Bedford who had made a fortune out of the brewery business.

Whitbread was an earnest idealist who saw Caroline as a much persecuted heroine; Brougham was something of an opportunist who saw in Caroline’s case a cause which could bring him fame.

They called on her— separately— and both told her of their admiration for her fortitude in her misfortune and how they would work for her.

With her usual exuberance she welcomed them.

It was fortunate for her that she had these supporters for those of the Prince were demanding that the Douglases repeat their accusations against her.

Whitbread, aware of this, forestalled the Princess’s enemies by asking in the House of Commons that Lady Douglas be prosecuted for perjury.

The affairs of the Regent and his wife were being discussed everywhere.

There was no doubt whose side the people were on.

On one occasion riding in Constitution Hill Caroline’s carriage passed that of Charlotte and the young Princess called to her driver to turn and follow her mother.

When the carriages were side by side the two embraced affectionately and through the windows engaged in an animated conversation.

A crowd collected.

‘Long live the Princess Charlotte!’ they cried. ‘Long live the Princess of Wales!’

The two smiled affectionately at the people and waved their greetings.

There were loud cheers and grumbles in the crowd too. Why should fat George come between mother and daughter? Why should they stand by and allow such wickedness?’

Mother and daughter bade each other a fond farewell and their carriages drove away in opposite directions were seen to turn and wave and look after each other longingly. There were tears in many eyes as well as indignation.

‘It shouldn’t be allowed,’ was the comment. ‘Someone should put a stop to it.’

No one was more aware of public opinion than Brougham; he came down vehemently on Caroline’s side. Meanwhile the Douglases were alarmed considering the penalties of perjury and Sir John wrote to the House of Commons on behalf of his wife explaining that the depositions they had made on oath before the Lords Commissioners were not made on such judicial proceedings which could legally result in a prosecution for perjury. But as they felt the fullest confidence in their statements they were ready to take the oath and swear before a tribunal, which if they were proved false could mean a prosecution for perjury.

They were eager to swear before such a tribunal, but they did not wish to take these oaths before one which was lacking in these legal liabilities.

Brougham laughed aloud when he heard this.

‘Ah,’ he cried to Caroline. ‘You understand. They’re bluffing. They know what this will mean. They will only swear at a public trial in which the Prince Regent would have to appear.’

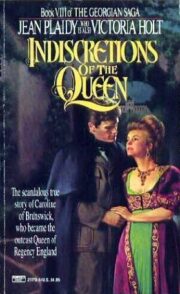

"Indiscretions of the Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Indiscretions of the Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Indiscretions of the Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.