He stood up and as he approached, she curtsied.

He said: ‘I should like to see a reconciliation. It’s not good, eh, what? The Prince of Wales and his wife living apart— not together. It’s wrong. You understand that, eh, what?’

She said she did understand but it was the wish of the Prince of Wales and nothing could alter that.

When he had left she was depressed thinking of him.

He is close to the brink now, she thought. And if I lost him I wouldn’t have a friend at Court.

There was always scandal circulating round the royal family and the King lived in perpetual fear of some fresh exposure. He could not understand why his sons should have this habit for creating trouble. It made him all the more determined to see that his daughters had no chance of doing so. He was glad there were no marriages for them. Only the Princess Royal had achieved it and she appeared to be living quietly with her husband. No husbands for the others, he had told himself grimly. They shall be kept here— under my eye and that of their mother. The Prince of Wales was creating fresh scandal with Lady Hertford— another of his famous grandmothers. Not content with refusing to live with the Princess of Wales he had returned to Mrs. Fitzherbert— a good woman and a beautiful one who should have been enough for anyone. But no, now it was Lady Hertford and God alone knew what fresh trouble was in store there.

And he was so anxious about Amelia, his youngest, his favourite, his darling.

He used to tell himself that no matter what trouble the others caused him there was always Amelia.

But even she caused him anxiety for she grew more wan every day. She had developed a lameness in her knee which he knew gave her great pain.

He would weep when he saw her and embrace her covering her face with kisses.

‘Your Papa feels the pain with you, my darling. You, understand that, eh, what?’

And she would nod and tell him: ‘But it is not such had pain, Papa,’ just for the sake of comforting him. His angel, his darling! How different from his sons.

The sea bathing at Worthing had done her good but only for a time. And he had to face the fact that as the months passed she grew no better.

She was his little invalid. He asked after her continually. ‘She is better today, Your Majesty,’ they would tell him; and he believed that they told him so on the Queen’s orders, for the Queen was determined that the King must not be upset.

His eyes were failing and he would put his face close to hers trying to tell himself that she looked a little better than when he last saw her; and whenever he asked her, she would always say, ‘Much better, Papa. Much, much better.’ And perhaps add: ‘I took a little walk in the gardens today.’

So even the best of his children gave him cause to worry. In spite of his expectations, trouble came from an unsuspected quarter.

The Prime Minister, Lord Portland, came to see him on a grave matter.

‘It concerns the Duke of York, Your Majesty, and a certain Mary Anne Clarke.’

‘Mary Anne Clarke!’ He had never heard of the woman. And Frederick couldn’t have made one of those marriages his sons were fond of making because he was married already. ‘Who is this woman?’

‘A woman, Your Majesty, of dubious character.’

‘ H’m. And what is the trouble, eh, what?’

‘A question has been raised in the House of Commons, sir, by a Colonel Wardle. He brings a charge against the Duke for wrong use of military patronage which as Commander in Chief of the Army he has been in a position to carry out.’

‘And what has this— woman to do with it?’

‘She is the Duke’s mistress, Your Majesty, and has been selling promotions which she has persuaded the Duke to give.’

‘Oh, God,’ cried the King. ‘What next?’

The Prime Minister said that he feared a great scandal as the House was insisting on an enquiry which would of course expose the Duke’s intrigue with this not very reputable young woman and would— if the charges were proved— result in his being expelled from the Army.

‘And so— there is to be this— enquiry.’

‘I fear so, sir.’

So this is the next disaster, thought the King. Can so much happen in one family? Am I dreaming it? Am I going mad? The great topic for the time was the scandal of the Duke of York and Mary Anne Clarke.

Mary Anne was an extremely handsome woman in her early thirties who had begun her life in Ball and Pin Alley near Chancery Lane. Her mother was widowed when Mary Anne was a child and later married a compositor, the son of whose master was attracted by the pretty child and had her educated. Mary Anne in due course married a stone mason named Clarke and later went on the stage where she played Portia at the Haymarket Theatre. Here she was noticed and became the mistress of several members of the peerage. At the house of one of these she made the acquaintance of the Duke of York who was immediately infatuated, and set her up in a mansion in Gloucester Place.

The doting Duke had promised her a large income but was constantly in debt and not always able to pay it; Mary Anne’s expenses were enormous and so to provide the large sums she needed she had the idea of selling promotions in the Army.

This was the sordid story which became the gossip of London. The Duke was in despair, but when Mary Anne was called upon to give evidence at the bar of the House of Commons she did so with jaunty abandon.

The Duke’s letters to her were read aloud in the House and these caused great merriment. All over London they were quoted— and embellished. This was the cause célèbre of the day.

The King shut himself into his apartments and the Queen could hear him talking to himself, talking, talking, until he was hoarse. He was praying too. And it was clear that he did not know for whom he prayed.

Amelia was sent to comfort him; and this she did by telling him how well she felt— never so well in her life.

And that did ease him considerably.

It emerged from the Select Committee which tried the case, that the Duke was not guilty of nefarious practices however much his mistress might have been; but all the same he had to resign his post in the Army.

He broke with Mary Anne, but he had not finished with her because she threatened to publish the letters he had written to her. These were bought for £7,000 down and a Pension of £400 a year.

But people went on talking of Mary Anne Clarke; and it was noticed that the King’s health was even worse than it had been before.

The Mary Anne Clarke scandal had scarcely died down when another and far more dramatic one burst on London, This concerned Ernest, Duke of Cumberland — the King’s fifth son.

Ernest was the last son the King would have expected to bring trouble. He had been sent to Germany to learn his soldiering where he had acquitted himself with honour; and when he had come back to England in 1796 he was made a lieutenant-general. Not only was he an excellent military leader but he had shown some skill in the House of Lords; he was an able debater and was regarded with respect by the Prince of Wales. The most likeable quality of the brothers was their loyalty to each other; and Ernest was determined that when George became King he would be beside him.

It was the night of May 10th. Duke Ernest had been to a concert and according to himself, retired to bed in his apartments in St. James’s Palace. Soon after midnight his screams awoke his servants who rushing in found him in his bed with a wound at the side of his head. One of the servants had fallen over the Duke’s sword which lay, on the floor and was spattered with fresh blood.

The Palace was soon aroused; doctors were sent for; and it was noticed that the Prince’s valet, an Italian named Sellis, was missing. One of the servants went to call him and ran screaming from the room. Sellis was lying on the floor, a razor beside him, his throat cut.

What happened in the Duke of Cumberland’s apartments on that fateful last night in May no one could be quite sure but there was rumour enough. The Duke’s story was that a noise in his room had awakened him and before he had time to light a candle, he had received a blow on the side of his head. He had started up, and as his eyes were becoming accustomed to the darkness he received another and more violent blow; he had felt the blood streaming down his face as he fell back on his pillows screaming for help.

That was all he could tell them.

The public was excited. This was far more dramatic than the recent Mary Anne Clarke scandal. A royal Duke attacked in his bed; his valet murdered. There would be an inquest. What would come out of that? Speculation ran wild.

The valet had a very beautiful wife. Everyone knew the weakness of the royal princes where women were concerned. Why should a valet attack a duke? Why should the valet be murdered?

The King was becoming quite incoherent.

‘This terrible scandal,’ he said. ‘What does it mean, eh, what does it mean, eh, what? This is worse than anything the Prince of Wales ever did. Ernest— what does it mean— what can it mean?’

There was one fact which kept hammering on his mind.

The valet had a beautiful wife. He kept seeing pictures of Ernest and a woman — a dark woman. Italian? Oh, God, help me, groaned the King. This family of mine will drive me mad.

The inquest was conducted with decorum and respect for the royal family. It was not easy to sort out the evidence. It seemed incomprehensible. Why should the valet attempt to murder the Duke and then commit suicide?

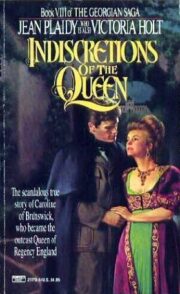

"Indiscretions of the Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Indiscretions of the Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Indiscretions of the Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.