But all the world should know now in what light he regarded her. He was dying and he was going to tell the world.

He called for paper.

‘I am going to make a will,’ he told Cholmondeley, and seeing the expression on his friend’s face he went on: ‘There is no point in hiding the truth. There may well be little time left to me. Do as I say.’

The paper was brought.

‘This is my last Will and Testament,’ he wrote. And the date: ‘The tenth day of January in the year of our Lord 1796.’

He wrote that he left all his worldly goods to ‘my Maria Fitzherbert, my wife, the wife of my heart and soul,’ who although she could not call herself publicly his wife was so in the eyes of Heaven and his. She was his real and true wife and dearer to him than the life which was slowly ebbing away.

Everything— everything was for Maria. Miss Pigot was not forgotten. He had already settled five hundred pounds a year on her for the rest of his life and it was his dying wish that on his death his family should provide a post for her perhaps as a housekeeper in one of the royal palaces.

He wished to be buried without pomp; and a picture of Maria was to be buried with him; it should be attached to a ribbon and hung about his neck; and when Maria died, he wished that her coffin be placed beside his and the inner sides of both coffins removed and the coffins soldered together in the manner employed in the burial of George II and his Queen Caroline.

He finished with a loving goodbye to his Maria, his wife, his life, his soul.

Then he felt better. She would know that he had sincerely cared for her. Their parting was a piece of folly which they should never have allowed to happen. He could never be happy in life without her; and he wanted her to know this as she would when his will was read after his death.

But he did not die.

In a few days’ time he had recovered from the excessive bleeding and the fond colour was back in his cheeks.

Caroline was happy. She had her baby and nothing else mattered. But there was inevitably one fear which haunted her; what if they should take the baby from her? The Prince showed little interest in the child; her only importance to him was that she made it unnecessary for him to live with her mother.

‘What do I care for him!’ said Caroline. ‘If I can keep my baby, I care for no one.’

Lady Jersey had hinted that the child would not be left under her control.

‘Let them try to take her away from me, cried Caroline clutching the child to her breast. This made Lady Jersey smile her haughty condescending smile, and Caroline felt she hated that woman almost as fiercely as she loved her child.

The christening took place at St. James’s, with the King, the Queen and the Duchess of Brunswick (represented by the Princess Royal) as sponsors. The Archbishop christened the little girl Charlotte Augusta.

‘Charlotte,’ laughed Caroline to Mrs. Harcourt, ‘after dear Grandmamma, the Queen of England, and Augusta after my own mother. I hope my little girl will resemble neither of them.’

Harcourt shrugged her shoulders. She was in duty-bound to report this to Lady Jersey who in her turn would report it to Her Majesty and Caroline would have advanced a little farther in the ill-favour of the Queen.

Yet, thought Mrs. Harcourt, Lady Jersey was perhaps not firmly established in the good graces of the Prince. True, he was fascinated by the woman, but she had heard that he repeatedly spoke— and with great longing— of Mrs. Fitzherbert and now that that lady’s friends had persuaded her to take a house in Town and enter Society, who knew what would happen? It was beginning to be said that if one would please the Prince, one should invite Maria Fitzherbert. An old and familiar pattern which must make Lady Jersey uneasy, though she gave no sign of it and seemed as confident as ever of her sway over the Prince.

The Princess Charlotte could one day be the Sovereign and therefore great ceremonies should attend her birth, but the Prince was smarting under Parliament’s methods of dealing with his debts and refused to receive the loyal ceremonies planned by the City of London.

‘I am too poor,’ he announced, ‘to receive these loyal addresses in a manner fitting to my rank. Therefore I would ask that the speeches ‘be written and presented to me.’

The Aldermen of the City were incensed. The Prince might have his dignity but theirs was as great. They could not depart from their old customs to please an impecunious prince. Therefore the ceremonies would not take place.

The City was indeed offended. The matter was discussed in the streets and the coffee houses.

‘Can’t afford it! You know what this means? He knows that she will have to receive the congratulations with him and he can’t bear to stand beside her while she does so. He hates her. And why? Because he knows she’s not his true wife, that’s why. He’s married to Maria Fitzherbert and he can’t abide this one.’

Why not? She was affable. She was German, it was true, but he was half German himself in any case.

The Prince of Wales was more unpopular with the City of London than he had ever been before. He was unhappy about this. He loathed the silences that greeted his carriage when he rode in the streets, and he thought longingly of those days of his youth when he was Prince Charming and everything he did was right. Then they loved him and hated his father; but since the King’s bout of madness that had changed. Not that the King was so popular. Royalty was not beloved in this changing world. There was the grim example from across the Channel always to be remembered. Only last year there had been riots in Birmingham. Flour had risen in price; a mob in Westminster had sacked the crimping houses; and the windows of Pitt’s house in Downing Street had been broken. This was how trouble had started in France.

In October, on his way to open Parliament, crowds had surrounded the King’s carriage shouting that they wanted bread. Stones had been thrown at the King and to his immense consternation, among them was a bullet.

There was no doubt about it. Royalty was not popular and it was unfortunate that the French had shown the world their method of dealing with it.

The Prince shuddered; but he was completely immersed in his own affairs; and his longing for Maria Fitzherbert surpassed any qualms he might have felt for the future of the Monarchy.

The King was preparing to call on the Princess Caroline at Carlton House to see his granddaughter, a journey of which the Queen could not approve, but His Majesty was very worried about the situation between the Prince of Wales and his wife.

‘He treats her very badly. No way to treat a wife, eh, what?’

The Queen replied that she was not altogether surprised. Caroline was certainly an odd creature, and vulgar by all accounts. They could not expect George— elegant, fastidious George— to enjoy living with a woman like that; it had been a great mistake to bring her into the country and when they considered that there was charming erudite Princess Louis whom he might have married!

The King’s eyes filled with tears. ‘Nice woman,’ he said. ‘Can’t see anything wrong with her. Pretty hair, nice figure— eh, what?’ He was determined to show her that at least one member of the royal family was on good terms with her.

Caroline received him affectionately, returned his kiss warmly, which delighted him. He liked to be kissed by pretty women— and in his eyes Caroline was pretty enough.

She sent for the child. What a lusty little creature!

‘He reminds me of her father when he was her age. You’d have thought then there wasn’t a prettier baby in the world. Ah well! Very healthy little thing, eh?’

Caroline held her baby in her arms and the King’s eyes filled once more with tears to contemplate her. He knew how she felt. He remembered his own feelings They were so enchanting when they were young— and then they changed.

Amelia hadn’t changed. She was still his darling. She would never bring him anxieties— except through her cough. He could not bear to think of Amelia’s cough so he gave his attention to young Charlotte.

‘Like her father, he said gruffly. ‘And has he been to see you?’

‘Not to see me. I have not seen him since the birth. But he comes to see the child.’

The King shook his head. ‘Bad,’ he said. ‘Bad. The people don’t like it.’

‘Well,’ cried Caroline with a shrill laugh, ‘my husband does not like me— which seems even worse.’

‘Must stop, you know. Should live together. There should be others. Madame Charlotte should have brothers and sisters, eh, what?’

Caroline shook her head. ‘He won’t, you know. He ignores me. I don’t exist for him ‘ ‘It’ll have to be stopped. He’ll have to do his duty.’

Caroline grimaced. ‘I don’t like being a duty much, Your Majesty.’

‘Ha,’ laughed the King. ‘Have to do your duty, you know. We all have to, eh, what?’

‘Your Majesty should be telling him this— not me. I’m ready to live with him. He’s the one who has made this separation.’

‘So you would welcome him, eh?’

‘Well, I wouldn’t say welcome— not unless he changed his ways. He would have to treat me as a wife. He would have to recognize me as the Princess of Wales. I won’t have that Jersey woman set up in my place while I’m treated as though I were one of her servants, because that’s how it was. Oh no, I should not accept that.’

‘There’s no reason why you should,’ said the King. ‘Nor shall you. Leave this to me. We cannot go on like this. It’s not natural, eh, what?’

Caroline agreed that it was not natural. But it was such a delight to have a child of her own that she was prepared to forget everything else.

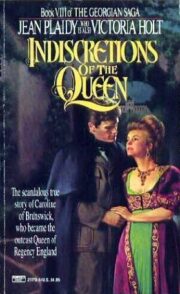

"Indiscretions of the Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Indiscretions of the Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Indiscretions of the Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.