Dr. Randolph took the letter which was handed to him. He had rehearsed the scene during the journey to the inn. He put his hand to his forehead and said: ‘My God, what shall I do? What can I do? There is nothing to be done but return home.’

‘Your Highness seems to be carrying a girl,’ Lady Jersey told Caroline.

‘While the horses are being prepared I will write a letter and I wish you to take it with all speed to Lady Jersey in Brighton.’

‘You would know,’ retorted the Princess, ‘being so clever.’

‘It is the method of carrying the child.’

His hands were trembling a little as he wrote the note. N had had grave news of his wife’s illness and was returning home at once. He must therefore postpone his visit to Germany. Lady Jersey would remember that he had been entrusted with a packet of letters by the Princess of Wales. He was wondering now whether he should entrust them to another traveller, who should be chosen by the Princess, or return them to Lady Jersey to hand to the Princess, and was now leaving for London where he would await Lady Jersey’s instructions. He trusted there would be no delay as he was anxious to return home to his sick wife.

‘Well, it is to the grandmothers we must turn to learn of these things,’ replied Caroline.

Lady Jersey saw that there was as little delay as possible. Grandmother indeed! thought Lady Jersey. At least she could be more proud of her appearance than Caroline could of hers.

She had spoken to the Princess of Wales who wished that the letters be returned to her. Dr. Randolph should therefore return the packet addressed to Lady Jersey at the Pavilion. They could be sent from London to Brighton on the post coach which set out from the Golden Cross Inn, Charing Cross.

‘Experience is always so valuable,’ said Lady Jersey; and while Caroline was thinking up a suitable retort, asked leave to retire.

Dr. Randolph sighed with relief, put the packet on the coach-post and returned home to his wife who was spending a few days in bed which she would have found a little irksome but for the promise of future glory as wife to the Bishop.

When she was alone, Caroline thought of the baby.

‘Girl or boy,’ she murmured. ‘What do I care? It’ll be my very own child.

And when it comes— perhaps even these last months will have seemed worthwhile.’

Caroline lay in her bed. Her time had almost come. Soon now, she thought, I shall have my very own baby. She had longed for this all her life. When she had visited the homes of humble people and delighted in their children, she had dreamed of the day when she would have her own. And now it was to happen. But she was in an foreign land. She had a husband who did not care for her.

She laughed at the expression. Did not care for her! He loathed her. He could not bear to look at her. As for her mother-in-law, she would be delighted to see Caroline sent back to Brunswick. She was alone in a foreign land, without friends, for there was no one here whom she could trust the King perhaps— but he was a sick old man and his position alone made him remote But when the baby came it would be different She and the child would be together.

Would they? She had heard the women talking. They had all said that royal children saw little of their parents. Their education was taken care of by their governors. Nonsense! she had told herself. I would never allow it. I would fight for this as for nothing else. And she would win. She was sure of it. There was one thing she had discovered about that precious husband of hers. He hated scenes— unless he could play the injured party, unless he could be the one who wept and suffered.

He certainly did not want to partake in scenes with her. He only wanted to avoid her.

She had put this to use when she had shouted at him. ‘Have your mistress by all means! But keep her out of my sight!’ He had looked as though he were going to faint with horror and had waved a perfumed kerchief before his nose as though to revive him or remove the odours of her person. But it had worked. Lady Jersey was less in attendance.

One of these days I shall insist that she leaves me altogether, Caroline told herself. But why brood on Lady Jersey when this cherished being was already announcing, in an unmistakable manner, his— or her— intention to come into the world.

A baby, she thought ecstatically. A baby of my very own!

The Prince of Wales paced up and down the chamber. Assembled there were the Archbishop of Canterbury and the King’s chief ministers of Church and State waiting for the birth of an heir to the throne.

Caroline’s labour had been long and she was exhausted; the Prince was in terror that the child would not be healthy or would be born dead There must be a child. He kept murmuring to himself: There must be. I could never— The suspense was unendurable.

At last they heard the cry of a child. The Prince hurried into the lying- chamber.

‘A girl, Your Highness. A lovely healthy little girl.’ There was no doubt of her health. She was bawling lustily.

Caroline lying in the bed, completely exhausted, cried out: ‘My baby. Where is my baby?’

They laid the little girl in her arms.

‘Mine God,’ she said, ‘it’s true then. I have a baby.’

‘A little girl, Your Highness.’

‘Mine God, how happy I am!’

The Prince was happy too. A boy would have been better, of course but there was no Salic law in England and the succession was secure.

He embraced the Archbishop; he shook hands with all who came near him. He was a father. He had done his duty.

I shall never be obliged to share a bed with that woman again, he thought.

The Royal Separation

THE Prince could not hide his relief.

He explained to his friend and Master of his Household Lord Cholmondeley: ‘I was terrified that something would go wrong. I cannot tell you, my dear friend, what the birth of this child means to me. If you could know all that I have suffered.’

Tears filled his eyes at the thought of his suffering, then he shuddered thinking of his wife. She seemed to him gross and vulgar and because she was so different from all that he admired in women she reminded him of the most perfect of them all: his dear Maria.

Oh, to be with Maria again, to be settled and happy; to return to her, often a little intoxicated as he used to be in the old days, to be aware of her concern, to listen to her tender scolding. Oh, Maria, goddess among women, why had she allowed him to marry this creature!

He turned to Cholmondeley: ‘If you could understand—’

Cholmondeley assured his master that he did understand; and he realized therefore that the birth of this child relieved him of a hateful burden.

‘I shall be grateful to this daughter of mine until the end of my days,’ said the Prince. ‘Pray God I never have to touch the woman again.’

‘There should be no necessity, Your Highness. The child is healthy.’

‘May she remain so. I have no intention of following my mother’s example and producing fifteen of them. Fifteen! It’s a joke. What a pity my parents were not more moderate. hey would have saved themselves a good deal of trouble.’

Cholmondeley could scarcely answer that without being guilty of les majesté so he remained silent.

The Prince was not expecting answers. He was in one of his lachrymose moods, full of self-pity; in a short while he would be talking of Maria Fitzherbert.

Cholmondeley believed that Lady Jersey must be a very clever woman— a witch perhaps— to be able to ding to her position as she did considering the Prince’s obsession with Maria Fitzherbert.

But the Prince was not looking healthy. His face— usually highly coloured— had a tinge of purple in it. A bad sign, Cholmondeley had noticed before. Well, it had been an emotional time; perhaps another bleeding was necessary.

‘Your Highness is exhausted. It has been such a trying time. Do you not think you should rest a little?’

‘I feel tired,’ admitted the Prince. ‘Bring me some brandy.’

Cholmondeley went to do the Prince’s bidding and when he, returned he found the Prince slumped in his chair. As he appeared to be suffering from one of those fits to which he was accustomed, Cholmondeley sent for the physicians.

The Prince, they said, was indeed ill, and bleeding was immediately necessary as it was the only effective way of baling with these unaccountable turns of his So the Prince lay on his bed, pale from much blood letting; and rarely had he seemed so wan and feeble.

The news spread through the Court: The Prince is seriously ill. He felt so feeble; he had no strength left. He had never felt quite so ill before in the whole of his life.

He asked that a mirror be brought and when he saw his face lying on the pillows, so white and drawn, so unlike his usual florid complexion, he was sure he was dying.

‘Leave me alone,’ he said. ‘I want to think.’

And when they had left him he lay thinking of the past— thinking of Maria.

That first meeting along the river bank and he had known that she was the only woman who was going to be of importance in his life. He had always known it.

Why had he allowed himself to be led astray?

Maria had refused him countless times. Good religious Maria, who believed in the sanctity of marriage and could only come to him through marriage. How right she was! And at last the ceremony in that house in Park Street— and the happy years.

He should have stayed with Maria. He should never have allowed himself to be seduced from her side. Only with Maria lay happiness. And he had broken her heart.

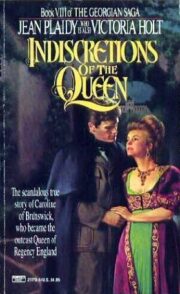

"Indiscretions of the Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Indiscretions of the Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Indiscretions of the Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.