There is surely a limit to what I need stand, she thought.

Malmesbury was looking sad, now and then catching her eye as though he would warn her. Warn her! Shouldn’t he warn the Prince? Who had set the pace?

Had she or the Prince? When she had come here she had been ready to be a good wife to him, to build up some family life, to give him some affection.

If only I could go home, she thought. I f I could explain to my father that this life is so wretched that no good can come of it! But that is impossible. Royalty must come before happiness. Royal people had no say in their destinies— royal Princesses that was. The Prince was determined to have his way, and even though he had been obliged to marry which was really because of his debts— he still intended to keep on Lady Jersey.

The meal over, Colonel Hanger lighted the great pipe which he affected.

Everyone laughed at George Hanger who did the most eccentric things; and no one dreamed of protesting even at that big ill-smelling pipe of his.

The Prince was smiling at Lady Jersey who was talking animatedly to him. He took her glass and drank from it. It was a token of the state of affairs between them.

In a sudden rage Caroline snatched the pipe from Colonel Hanger’s mouth and putting it in her own, puffed smoke across the table into the Prince’s face.

There was a hushed silence about the table. She was aware of the Prince’s blank stare, of the glitter of Lady Jersey’s snake-like eyes.

Caroline burst out laughing. She had to do something to put an end to that awful silence.

Everyone was embarrassed; the Prince looked helpless; then ignoring her completely he began to talk of the play which was running at Drury Lane.

Caroline knew nothing of the play. She could not join in.

She sat smiling to herself. She was not going to let any of them know how unhappy she was.

The Prince had sent for the Earl of Malmesbury who came to him rather sadly guessing that after that strange exhibition at the table the Prince was going to criticize his consort and because Malmesbury had brought her over to blame him.

He saw at once that the Prince was really angry. ‘Well, Harris,’ he said, ‘you have seen that extraordinary display of bad manners. How do you like this sort of thing?’

Malmesbury murmured that he did not like it at all, but he thought that the Princess was in a strange country and was not yet sure of herself.

‘Not sure of herself!’ echoed the Prince. ‘My dear Harris, what antics do you think she will perform when she is? Why on Earth did you not write to me from Brunswick and tell me what sort of woman you were bring over?’

‘Your Highness, there was nothing of which to complain against the Princess’s moral character.’

‘You could bring this— this woman over, knowing what you did. I do not consider you served me very well.’

‘Your Highness, His Majesty sent me to Brunswick not on a discretionary commission but with the most positive commands to ask the Princess Caroline in marriage.’

‘I see, said the Prince bitterly. ‘You were obeying the King and you did not see it as your duty to warn me.’

‘Your Highness, replied Malmesbury somewhat sharply, ‘while I knew that the Princess had much to learn I did not conceive that Your Highness would make up your mind so to dislike her.’

The Prince looked exasperated. ‘You see what she is like— Do you think she will ever inspire respect in my friends?’

‘I think, with encouragement, she will improve.’

‘With encouragement, Harris, you are always so discreet and diplomatic, are you not?’

‘It is my business, sir, to cultivate these qualities.’

‘You manage well, I do assure you. But that has not helped me very much I fear. I see nothing but disaster through this marriage— nothing but disaster. This woman is— impossible. She revolts me. She is not even clean.’

Malmesbury looked hurt. He understood, of course. Had he not tried to instill in her the importance of freshness; had he not warned her of the extra- fastidiousness of the Prince?

And she had lightheartedly refused to consider his advice. He was exasperated with her, but desperately sorry for her too.

And through her he had lost the confidence of the Prince who could never quite forgive those whom he thought considered his father before himself.

‘And what do you think will be the outcome of this marriage which you, Harris, have arranged?’

‘I think the outcome will depend on you, sir, and Her Highness. And I must remind Your Highness that it was His Majesty who, with your consent, arranged the marriage. My commission was merely to go to Brunswick and make a formal offer. This, sir, I did to the best of my ability.’

The Prince shook his head mournfully. ‘I know, I know. But a word of warning, Harris. One word of warning. What disaster might have been averted then!’

Malmesbury could only look regretful; but as he left the Prince’s apartment he knew that he was expected to take some share of the blame for the marriage and the Prince would always remember it against him.

He saw the Princess.

‘I would to God, my lord,’ she said, ‘that I had never Come to England.’

‘Your Highness will grow accustomed to your new life.’

‘I will never grow accustomed to life with him. Nor shall I have to. Because I tell you this, my lord: As soon as I am with child he will never see me again. That is what he waits for. The best news I can give him is that I am with child.’

‘It is the best news you can give the nation.’

‘Oh, my dear Ambassador, who is always so correct— and therefore so different from me. Yes, it will be good news. If I can provide the heir the nation will be pleased. But he will be pleased— not so much because I have give them the heir but because he can then be rid of me.’

‘Your Highness, you remember when we were in Brunswick I implored you to be discreet and calm.’

‘You implored me to do so much, you dear good kind man. But you could not change me, could you? But I love you for trying.’

Malmesbury flinched. She would never learn. She would go on making wild and reckless statements, but she would not wash as she should; and she would never please the Prince of Wales.

‘You see, my dear lord, I shall never change. I shall always be your naughty Caroline of Brunswick.’

‘I believe that if you would try very hard to behave in a manner which would not shock the Prince—’

‘Shock him. He is the right one to be shocked. You know, don’t you, that he sleeps with that Jersey woman?’

Malmesbury turned away, his expression pained. What could he do to help such a woman? Had he not done his utmost; and all his efforts had clearly been in vain.

There was nothing he could do, thought Malmesbury.

The marriage was doomed.

The King was equally concerned for the marriage. The Prince disliked his bride and that was bad; but whatever happened appearances must be kept up.

The Queen came to his apartments. How their relationship had changed, thought the King sadly. In the days before his illness she would never have dared to come without an invitation. Now, of course, she was so necessary to him. A good wife, he thought. And he remembered all the children who had given him so much cause for anxiety: The girls who ought to have husbands found for them for they were growing restive and in a few years would be too old for marriage; the boys with their wildness. But there was always dearest little Amelia, the light of his life, he called her. His dearest youngest daughter who was yet too young to cause him any concern; he would like her to remain a child— a lovely innocent child for ever. And even she worried him because of that cough of hers. He himself prescribed her cough mixture and always impressed on her the need to take it; and when she put her arms about his neck and kissed him and called him dearest Papa, everything that he had suffered, the years of marriage with a woman who did not greatly attract him, everything seemed worthwhile.

He still had the verses which Miss Burney composed on his recovery after that frightful illness and which darling Amelia had presented to him. He remembered how sweet the child had looked and how she had spoken her piece which was: The little bearer begs a kissFrom dear Papa for bringing this. He would always treasure the memory. And whatever happened he had his darling Amelia.

Now he asked the Queen how Amelia’s cough was and when he heard that it was better he was much relieved.

‘I must bring up this matter of George’s debts to Parliament,’ he said. ‘I suppose they will be generous.’

‘It is the price he has to pay for his marriage.’ The Queen’s big crocodile mouth widened in a smile. ‘I daresay he is thinking the price a high one. Well, we all have to pay for our follies.’

‘You think he cannot take to the young woman, eh, what?’

‘I am sure he cannot. You will admit that she is a— spectacle.’

‘I thought she was a handsome enough young woman.’

‘Not handsome enough for George, evidently.’ The Queen gave a quick laugh.

‘Poor child,’ said the King compassionately. ‘It is not easy.’

‘Scarcely a child. I was some ten years younger when I came here.’

‘I know it. I know.’

‘I feel Louise would have been a better choice. Well, it is too late now. I can feel almost sorry for George.’

The King frowned. ‘I hope there will be no troubles about these debts. They are enormous. Some £620,000. How did he ever manage to let them grow to that extent, eh, what?’

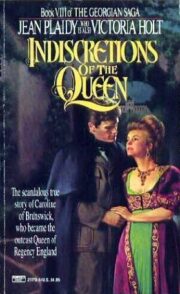

"Indiscretions of the Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Indiscretions of the Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Indiscretions of the Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.