‘My dearest, I know you seek to comfort me. Charlotte is excited. She is like Caroline. They crave constant excitement. It is a sort of madness— no— no. It is a compulsion they have. I pray God Charlotte will be happy when the excitement is over.’

‘The excitement will go on for a time and perhaps she will soon have a child and that will sober her.’

‘Determined as ever to look at the brightest side, I see.’

‘Well let us at least enjoy that while we can. In any case, there may not be another side. Who shall say?’

He pressed her hand. ‘You are right as usual.’

She smiled at him, her eyes still a little anxious. Since he inherited the Dukedom some two years before, life had been less carefree. His father had been a spendthrift and Charles had taken over an almost bankrupt country. He had determined to bring his country to prosperity and practised economy as far as he could; but that was not easy and he had been trained as a soldier rather than a statesman. But Madame de Hertzfeldt was as good as any minister; he rarely made a move without consulting her and he had proved again and again that this was wise. It was she who had helped to arrange this match for Charlotte; and she would do the same for Caroline when the time came. She had suggested that the Princesses be brought up with religious freedom so that they could in due course become either Protestant or Catholic according to the religion which their future husbands might follow. This, she had pointed out, would make it so much easier to find husbands for them, since many good matches were lost through a difference in the religion of either parties.

What a Duchess she would have made! And he had to be content with Augusta who was constantly reminding everyone at Brunswick how much better affairs were managed in England under the rule of her brother King George III.

‘So,’ she said, ‘we will think only of the wedding celebrations and deal with future problems when they present themselves.’

The Duchess was talking to her daughter Charlotte, soon to be a bride.

‘Of course I could have wished we could have had an English Prince for you.

My brother’s son, the Prince of Wales, would be— let me see— Twenty, would it be? Yes, I should think twenty, and surely it is time he married, but do you think they would marry him to a Princess of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel? Oh no! The very suggestion would give my sister-in-law an apoplectic fit. How I hated that creature. She— Queen Charlotte— was one of the reasons why I was anxious to get away from England.’

‘Well, Mamma,’ said Charlotte pertly, ‘it is no use repining for the loss of the Prince of Wales now that I have my Frederick William. Würtemberg will have to do. And as the marriage is to take place within a day or so even if my wicked old aunt Queen Charlotte relented and sent me your nephew the Prince of Wales it would be, to say the least, a little awkward.’

‘Charlotte, you really are impertinent,’ said her mother mildly.

‘What do you expect when I am named after that wicked sister-in-law of yours?’

‘You happen, Charlotte, to be speaking of the Queen of England.’

‘And so, Mamma, were you a moment ago and every bit as disrespectfully.

Confess it.’

Oh dear, thought the Duchess. She would never be able to control these children of hers. It was the same with Caroline. The girls had their own way. But what can I do? she asked herself. I am not in command here. It is always Madame de Hertzfeldt. She is the Duke’s confidant. She decides all matters, even those concerned with my children. What a situation! I wish I’d never left England. She shivered. Fancy being there, with George expecting her to live with her sisters like nuns in a nunnery. No, this was preferable, even though she had an unfaithful husband who cared little for her, and children whom she could not control. Her children alarmed her. She could not bear to be in the company of her eldest boys. They seemed a continual reproach. Was it her fault? What had she done to produce those three boys who would never be able to rule? The youngest boy, thank God, was normal; and his father doted on him, and was terrified that some harm was going to befall him-his only normal son. He cherished the boy almost as much as he did Madame de Hertzfeldt— though not quite— No one could be quite as important to him as that woman!

Then there were the girls who were so wayward that they always seemed to get the better of her. They are so German, she decided ; and I am so English. Sometimes she felt it was not such a bad thing that she had a strong-minded woman like Madame de Hertzfeldt to help her control the girls. That woman, thought the Duchess petulantly, would control anybody.

‘Mamma,’ Charlotte was saying, ‘I have matters to which I must attend. So you must give me permission to leave you.’

The Duchess nodded and shaking her head sank down on to her sofa and stared blankly before her. How she had disliked this room! When she had first seen it, it had seemed so primitive after the apartments of St. James’s, Hampton Court and Kensington Palace. But she had grown accustomed to it. And she had not really been sorry to come here. After all, a woman must marry— and they might have given her a less attractive husband. Charles had at least been a hero when he had come to England to marry her. Not that he had been quite as handsome as she had pictured him, but the people had liked him. She remembered how they had been cheered at the Opera while George and Charlotte were received in silence. What a triumph! Serve them right. It was all jealousy— Charlotte’s fault, she was sure. George would never have had the gumption. Their mother had completely dominated him at that time, and he had done everything that she and Lord Bute told them.

But Charles had talked freely on English politics, which had angered them, and so instead of lodging him at one of the royal palaces they had put him in Somerset House and made their disapproval very clear to him as he was obliged to stay there without a royal guard. She too had been in disgrace for attempting to meddle in state affairs. And she had too! To think that she had helped to break up her brother’s romance with Sarah Lennox and as a result he had had Charlotte.

Not such a good move really— although Sarah Lennox was a silly little thing and if she had married George would probably have been no friend to the Princess Augusta.

All past history— but one could not help recalling it at times like these when there was a wedding in the family. And so she had come here and been horrified to see what a poor place the palace was and even more so when Charles had made it clear that he had no intention of giving up his mistress because he had acquired a wife and that the latter was of no great importance in his life— although he would endeavour to give her children— while the other woman remained supreme— What a position for a proud Princess to be forced into— and an English Princess at that. But she had succumbed and done her duty and produced her sons — two mentally-deficient, one blind, then her daughters and another boy— all of whom seemed brilliant in comparison with their brothers.

At least I have my children, though I have no control over them, she thought fretfully. They take no notice of what I say, and it is all due to the fact that they know who really rules here with the Duke. One would have thought he might have become tired of her by now. But that would not do. Who knew what arrogant upstart might take her place? The Duke alas was a very sensual man and was not entirely faithful even to Madame de Hertzfeldt; but of course none of his other peccadilloes were serious or long lasting; and on more than one occasion she had reported them to her great rival in order that they could be brought to a hasty conclusion. She supposed that she accepted Madame de Hertzfeldt who was such an admirable woman in so many ways, and while she took command of affairs she always openly paid the correct respect to the Duchess.

So the Duchess must be content with her lot for she would have been far less happy in England, she knew, living a life of dreary spinsterhood. She had realized that in February 1772 when she had gone back to England at the time of her mother’s death; but for the fact that her mother had wished to see her and they could not ignore her dying wish; Charlotte and George would have prevented her coming. As it was they had given her a little house in Pall Mall instead of lodging her at one of the royal palaces.

She recalled her anger and how she had almost returned to Brunswick before the funeral. It would seem that she was to be slighted everywhere.

How strange when she considered what a forceful young woman she had been at home in England as the Princess Royal.

But Charles had changed her. From the moment she had realized he intended to be master and had accepted her inability to prevent it, she had sunk meekly into her place, had borne his children— and the fact that the three boys were abnormal had perhaps contributed to her meekness accepted Madame de Hertzfeldt and even allowed her children to have some respect for the woman.

Now she sighed and thought of Charlotte soon to leave her home for a new life with a husband.

‘I pray,’ said the Duchess, ‘that she is more fortunate than I.’

Charlotte was a dazzling bride, for she was very pretty.

‘When she has gone,’ Caroline told the Baroness, ‘I shall be the prettiest princess at the Court because being the only princess I must be the prettiest.’

‘You occupy your mind with matters of no importance,’ she was reproved, at which she retorted that her beauty was of great importance. Did the Baroness forget that one day very soon— she would have to please a husband?

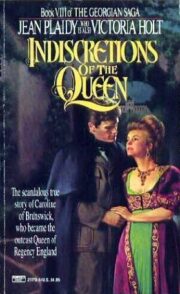

"Indiscretions of the Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Indiscretions of the Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Indiscretions of the Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.