The Prince’s manner was more gentle towards his father than it had been in the past and this helped to subdue the animosity between them. The King was sad rather than angry. How many sleepless nights this son of mine has given me, he thought. But he was young and now he is beginning to realize his responsibilities.

He’ll do his duty now.

‘Your Majesty, I have today written to Malmesbury telling him to expedite matters over there.’

The King looked pleased. No sign of truculence. After all these years of resistance to doing his duty, the Prince was now prepared to take this step.

Excellent, eh, what? thought the King.

‘I hope she proves as fertile as your mother.’

God forbid, thought the Prince. Surely even his father realized that thirteen— and there might have been fifteen— was more than enough with which to burden the State.

‘I feel optimistic that we shall not disappoint Your Majesty.’

The King inclined his head and, determined to come to the point while he was in this tolerant mood, the Prince said quickly, ‘There is one matter on which I should like to consult Your Majesty.’

‘Yes, what is it, eh?’

‘Your Majesty will know that I had a connection with a certain lady which— er— no longer exists.’

‘I am glad to hear it no longer exists. It must no longer exist, for if it did that could provide very grave consequences you understand, eh, what?’

The Prince kept his temper and went on, ‘I know this full well, Your Majesty.

The connection no longer exists but I feel certain obligations towards the lady.’

The King grunted but the Prince hurried on, ‘During this connection the lady received three thousand pounds a year, which I intend to continue although my connection with the lady is completely severed. But I should like Your Majesty’s assurance that in the event of my death before that of the lady this pension should be continued.’

The King interrupted him. ‘I know I know—’ Then he softened. ‘This lady is Maria Fitzherbert, a comely widow.’ The King’s mouth slackened a little, he was looking back over the years before he had been ill; he was thinking of all the temptations which had come his way and how he had resisted them. They would be surprised, these people who surrounded him, if they knew that in his way he was as fond of women as his sons were proving themselves to be.

Sarah Lennox making hay in Holland House. What a little beauty she had been! And he would have married her. He certainly had it in his mind to do so.

And before her there had been Hannah Lightfoot, the beautiful Quaker girl. He had better not think of her. But he had done what he had thought right and married plain homely Princess Charlotte and tried to put other women out of his mind.

Elizabeth Pembroke— what a beauty! There was a woman he could love. She was at the Court and he had to see her every day and he had to remind himself that he was married to Charlotte and that it his duty to set an example. Duty.

Always duty.

Plain Charlotte instead of beautiful Sarah Lennox. Fifteen children and not an illegitimate one among them. There had been Hannah of course but that was before that was all in the past. Since his marriage he had been a faithful husband — except in thought, of course. But how could a man help his thoughts?

And because of his own feelings, he could understand the Prince’s. This Maria Fitzherbert was a good woman by all accounts. Pity she had not been a Protestant German Princess instead of a Catholic English widow. He believed she would have had a good influence on the Prince. In fact he knew she had had this because she urged him to live less extravagantly, to gamble less, to drink less, to give up his more disreputable friends.

Oh yes, this Maria Fitzherbert was entitled to a little consideration. And he, from remembering certain incidents his own past, would be the first to admit it.

‘Your— your sentiments do you credit,’ said the King. ‘I think this lady has a right— to such consideration. I believe she has always behaved in a— a very admirable manner, eh, what?’

‘It’s true— true!’ declared the Prince fervently.

The King nodded. ‘Then we will settle this matter. But it had better come through Loughborough. The Lord Chancellor is the man who should deal with it.

Tell him to bring the matter to my notice. Have no fear. I find these sentiments do you credit.’

‘I thank Your Majesty with all my heart.’

The King laid his hand on his son’s shoulder and his eyes filled with tears.

There were tears in the Prince’s also.

How pleasant— how unusual— for them to be friends. He’s changed, thought the King. He’s settling down at the prospect of marriage More amenable. More reasonable. We shall get on now. The Prince was thinking: His madness has changed him. Made him mellow— reasonable. Perhaps we can be more friendly now. Within a few days the Prince received a letter from Lord Loughborough in which the Lord Chancellor wrote that he had presented the Prince’s problem to the King concerning the provision he had thought proper to make to a lady who had been distinguished in by his regard, and asking that in the unfortunate event of his death His Majesty would see that it was provided. His Majesty wished to convey that His Highness need have no anxiety on this account.

The Prince was delighted.

He wanted Maria to know that he had not in fact deserted her. He waited her to know that although he could not see her she was in his thoughts.

He could not write to her because he had given his word that he had broken off all connection with her. But he did want her to see that letter.

He had an idea. He would send it to his old friend Miss Pigot, who would certainly show it to Maria. He sat down at his desk immediately and dashed off a letter.

Miss Pigot could not curb her excitement when she saw that handwriting on the envelope. And addressed to her! It could only mean one thing. He wanted her to make the peace between himself and Maria.

She opened the envelope and the Lord Chancellor’s letter slipped to the floor.

She picked it up, looked at it in astonishment, and then turned to the Prince’s.

He did not wish his dear friend Miss Pigot to think he had forgotten her. His thoughts were often at Marble Hill; and he sent her the enclosed letter so that she should show it to one whom it concerned which would in some measure explain the regard he had for that person.

Miss Pigot re-read the Chancellor’s letter, grasped its meaning, and rushed to Maria’s bedroom where she was resting.

‘Oh, Maria, my dear, what do you think? I have heard from the Prince.’

‘ You— have heard?’

‘Oh, it is meant for you, of course. That’s as clear as daylight. Here’s a letter from the Chancellor about your income.’ Maria seized it and her face flushed angrily.

‘I shall not accept it,’ she said.

‘But of course you’ll accept it. You’ve debts to settle, haven’t you? Debts you incurred because of him. Don’t be foolishly proud, Maria. He wants you to have the money.’

‘Is he paying me off as he did Perdita Robinson?’

‘This is entirely different. She had to blackmail. You didn’t even have to ask.’

‘I shall not take it. You may write to His Highness and tell him so, since he sees fit to correspond with you about affairs which I had thought should be my concern.’

Miss Pigot left Maria and went to her room to write. She did not however write to the Prince but to Mr. Henry Errington, Maria’s uncle, telling him what had happened and advising him to come to Marble Hill to make Maria see reason.

He arrived within a few days and talked earnestly to Maria Had she settled her debts? She had not. And did she propose to do so from the two thousand a year which she had inherited from Mr. Fitzherbert? It was impossible, she realized. And this talk of a pension seemed to her a finality.

‘Maria,’ said Uncle Henry, who had been her guardian since the days when her father had become incapacitated through illness and who had indeed introduced her to her first and second husbands, ‘will you leave this matter to me?

What has happened was inevitable. You should emerge from that affair with dignity. This you cannot do if you are to be burdened with debts for the rest of your life. You must accept this pension, which is your due. Settle your debts in time; and then return to a solvent dignified way of living. It is the best way. Don’t forget I am your guardian and I forbid you to do anything but what I suggest.’

She smiled at him wanly. ‘Uncle I am sure you are right.’

‘Then will you allow me to settle these financial matters for you?’

‘Please do, Uncle. I do not wish to hear about them.’

Henry Errington kissed her cheek and told her that he was glad she had such a good friend as Miss Pigot to be with her.

‘I have much to be thankful for I know, dear Uncle,’ said Maria. ‘And don’t worry over me. I am recovering from the shock of being a deserted wife.’

But when she was alone, she asked herself: Am I? Shall I ever? How different life would have been if Uncle Henry had introduced her to a steady country gentleman like Edward Weld or Tom Fitzherbert, then she would have settled down to a comfortable middle age.

But what she would have missed! That’s what I have to remember, she told herself . I have been ecstatically happy. I must remember that. And remember also that in the nature of things that kind of happiness does not last. Then she laid her head on her pillow and wept quietly for she had lost.

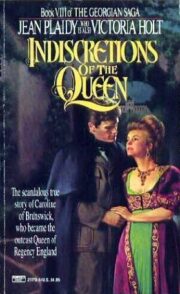

"Indiscretions of the Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Indiscretions of the Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Indiscretions of the Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.