So they had come back to Marble Hill and here they were.

Maria had always been particularly fond of Marble Hill— a fine house which had been built by Lady Suffolk, one of the mistresses of George II, as a refuge for her old age when she should no longer please that monarch.

It had delightful grounds which had been planned by Bathhurst and Pope, and the flowering shrubs, particularly in the spring, were charmingly colourful. Maria loved the lawns which ran down to the river and were bounded on each side by a grove of chestnut trees. From the grotto, a feature of the garden, there was a very pleasant view of Richmond Hill. One glance at the house explained why it had received its name; perched on an incline it really did look as though it were made of marble, so white was it; and it owed its graceful appearance to those excellent architects Pembroke and Burlington.

Maria was sitting in her drawing room, a piece of embroidery in her hand, but she was not sewing; she was looking wistfully out over the lawns to the river.

Miss Pigot came and sat beside her, and Maria forced herself to smile.

‘How dark it is getting— so early,’ said Maria. ‘The winter will soon be with us.’

But she was not thinking of the weather.

‘You might as well say what’s in your mind, Maria,’ said her faithful companion. ‘It doesn’t do any good to bottle it up.’

‘I suppose not.’

‘If you’re thinking of him you shouldn’t try to pretend you’re not. Is there something on your mind?’

Maria was silent. ‘It can’t be true,’ she said. ‘No, of course it’s not true. And I am thinking of him. I thought going away would help to cure me, but I fear I never shall be cured.’

‘He’ll come back,’ said Miss Pigot firmly. ‘I just know he will come back.’.

Maria shook her, head. ‘I would not have believed it possible that he could have written to me in that way— so cold— after all these years— after—’

‘It was done in a had moment, Maria my dear. He’s breaking his heart over it now, I shouldn’t be surprised.’

‘I should, Piggy, very. He is at this moment with Lady Jersey, not giving me a thought— or if he is to congratulate himself for being rid of me.’

‘Now you don’t believe that any more than I do. He’d never feel like that.

He’s had a little flash of temper. And you know, my dear, you have lost yours once or twice. In your quarrels you haven’t always been the meek one, have you?’

‘Find excuses for him, Piggy. You know that’s what I want you to do.’

She looked so forlorn, so tragic sitting there that Miss Pigot went over and kissed her.

‘Dear Pig, at least I have you. That is something to be grateful for.’

‘I’ll be faithful till death.’

‘Those were exactly his words.’

‘And he meant them— in his way.’

‘In his way?’ said Maria bitterly. ‘I know what that means. Words— words and no meaning behind them.’

She was silent for a while and Miss Pigot did not attempt to break that silence; then Maria began to talk of that ceremony in her drawing room in Park Street.

‘I would tell no one but you. I promised it should be a secret and I have kept my word. I should have known what to expect shouldn’t I, when Fox stood up in the House of Commons and denied that we had ever been married? And the Prince let it pass.’

‘You left him then. Remember how unhappy you were? But you went back to him, didn’t you?’

‘He was my husband, whatever Mr. Fox said. I didn’t forget that.’

‘If he was then, he is now. So you shouldn’t forget that either.’

‘ He has chosen to forget, and I shall not remind him. What use would it be?

But I can’t stop thinking of those happy days. I think the happiest were when we were most poor. Poor! What he thought of as poor. Do you remember when there were bailiffs at Carlton House and the King would not help and so the Prince sold his horses and shut up the state apartments at Carlton House and we went down to Brighton? But we were determined to economize; we determined to settle his debts gradually— and so we took that place in Hampshire. I think those days at Kempshott were the happiest of my life, Piggy. If he had been simply a country gentleman like my first and second husbands, I think we should have been happy.

I understand him as no one else does. I could make him happy— but he does not think so.’

‘Of course he does. This Jersey affair will pass like the others, Maria. He’s a boy— rather a spoilt boy I admit— but we love him for what he is. He’ll be back.’

‘I see that you have not heard the rumours.’

‘Rumours? What rumours?’

‘He’s in debt again. His creditors have to be appeased. The King and Mr. Pitt have put their heads together and are offering him a condition.’

‘Them and their conditions! They always make conditions!’

‘This time it is marriage.’

‘Marriage. How can he marry? He’s married already.’

‘The State would not say so.’

‘Then the State would be lying. Have you and he not made your vows before a priest?’

‘We have, but if the State does not recognize them— Remember the case of the Duke of Sussex. He had made his vows but the courts decided he was not married.’

‘I know. It’s wicked.’

‘But it’s fact. I am only the Prince’s wife while he acknowledges me as such.’

‘That’s nonsense.’

‘I know that in the eyes of God and my church, I am the Prince’s wife. But he does not accept that. That is why he has agreed to marry.’

‘Agreed to marry. It’s lies.’

‘So I told myself, but rumour persists.’

‘There’ll always be rumours.’

‘But this rumour is on very firm foundation. I even know the name of the Princess of Wales elect.’

‘What?’

‘Caroline of Brunswick. Niece of the King.’

‘It’s all a pack of nonsense,’ said Miss Pigot.

But Maria only shook her head. ‘It’s true,’ she said. ‘And it’s the end. I have really lost him now.’

In the Queen’s Lodge at Kew the Queen was having her hair curled and reading the papers at the same time. She supposed now there would be a spate of lampoons and cartoons about the Prince’s proposed marriage once it was announced. At the time it was, of course, a secret; but it would not be so much longer.

She sighed. She did hope that nothing would happen to upset the King; since that last illness of his— she shuddered. One could scarcely call it an ordinary illness. All those months when his mind had been deranged and she had suddenly come into power had been most uneasy. It was not that she did not wish for power; she did. She was beginning to grasp it, and she had the King’s condition to thank for it— if thank was the right word in such circumstances. But she faced the fact that the King terrified her. Whenever she heard him begin to gabble; when she saw those veins projecting at his temples; she was afraid that he was going to break out into madness— and violent madness at that.

Dear little Kew, as she always thought of it, had lost its serenity. She had been delighted with it from the first day when she had gone to live in the Queen’s Lodge which was really one of the houses on the Green. The Dutch House was close by and there the Prince of Wales had lived before he had his own establishment— first apartments in Buckingham House and then with greater freedom in Carlton House. There across the bridge along Strand-on-the-Green many of the members of the household lodged. Certainly Kew was not like living at Court; it was even not like a King’s residence. Perhaps that was why she and the King had always been so fond of it.

But Kew had changed; it was full of memories. She remembered how they had brought the King from Windsor when it had first been known that he was mad, and sometimes at night in her sleep she was disturbed by the sounds of that rambling voice going on and on, growing more and more hoarse; she thought of that occasion when the King had seized the Prince of Wales by the neck and tried to strangle him and how the hatred shone in those mad eyes of his; she remembered a time when he had embraced their youngest daughter Amelia until the child had screamed aloud in terror because she thought he was going to suffocate her. And that was love!

She would never forget the agonized look in those poor mad eyes when his beloved child had been dragged from him and they had tried to force him into a strait-jacket.

Memories of Kew! The King walking the grounds with his doctors, shouting himself hoarse, beating in time to imaginary music, shaking hands with an oak tree which he thought was the Emperor of Prussia. This had changed the face of dear little Kew.

And, thought the Queen — how can we know when it will break out again, and if it does and there should be a Regency— the Prince will do everything he can to curb my power. But she would not let him because Mr. Pitt was on her side and Mr. ‘Pitt was Prime Minister and cared little for the Prince of Wales. The Prince had allied himself with Fox and the Whigs and that was enough to make Pitt stand against him.

Mr. Pitt and I will rule between us, thought Queen Charlotte; and she wondered how she could have come to hate her eldest son so much, he, whom when he was a baby and a young boy, she had idolized. The others altogether had not meant half so much to her as her first-born; and now she hated him.

Strong feelings for a mother— and such a plain little woman. Ah, but then it was everyone. had thought her plain and insignificant for so many years that now she saw the chance of exerting her power she seized it.

The King who had determined to keep her in her place— which meant constantly bearing children— had had his way since their marriage. She had given him fifteen children. Surely, she had done her duty? But now he was a poor shambling than his living in creature— older than his years, living in constant fear that his madness would return.

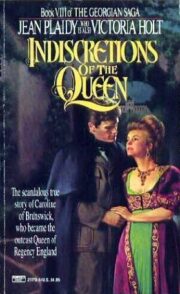

"Indiscretions of the Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Indiscretions of the Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Indiscretions of the Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.