The next morning Dammler was rudely surprised to be jostled from a sound sleep by his doughty hostess in person, decked out in the ugliest peignoir he had ever seen-cerise and peacock blue, with black swansdown trim. Now who would have thought the Pillar had such a streak of barbarism buried beneath all those stays? In public she appeared in nothing but black.

“It’s ten o’clock, Allan,” she said.

"Ten o’clock,” he repeated stupidly. “Ten o’clock, eh?” What, he wondered, was the magic significance of the hour.

“Church is at eleven o’clock,” she told him.

“Church?!” he asked in alarm.

“Church,” she repeated, staring down her parrot nose at him. “I trust you go to church on Sunday.”

“Yes. ›Oh,yes,” he told her. Good Lord, what had he gotten into? She’d be enrolling him in Bible classes next.

“I’llsend up cocoa and toast. We’ll eat an early lunch after.”

“Thank you,” he said in a small voice, then when she left, put his head beneath the pillow and laughed till his valet came to see if he was ill.

“My best morning coat, Scrimpton. I am going to church.”

“Yes, my lord,” Scrimpton answered, taking the news like a rock.

At five minutes to eleven, the Marquis of Dammler and the Dowager Countess of Cleft caused a considerable stir when they walked up the aisle of Bath Abbey, not least in the heart of Miss Mallow, who stared after them as though they were a pair of tigers or elephants. Clarence nudged her in the ribs and nodded sagely, as though to say, there he is, chasing after you again. Her mother glanced at her, too, but with an unreadable face that was trying not to smile.

Once again Prudence felt she would be accosted by Dammler after church, but on this occasion he could hardly be accused of dallying. He looked at her several times and smiled the smile that went with his shrug, though in company with the Pillar, one did not shrug. Coming to her was physically impossible for the crowd that hovered around, having heard who was visiting the Countess and wishing to meet him.

“We'll just wait till those few people go along, to say how do you do to Lord Dammler,” Clarence suggested. His niece would have none of it. She had him into his carriage and on the way home before anyone got a look at his jacket.

“Well, he knows where you stay. I gave him your address when he called in London. We will be seeing him before the day is out.”

When he failed to appear, Clarence decreed that he had been driving all night, and was likely tucked into his bed, not wanting to show Prudence such a harried face. "Those handsome fellows are as vain as ladies about their looks. He will be along tomorrow.”

Dammler would have liked to have gone along to the memorized address that same day, but the Pillar had other plans. She had invited the presiding minister at Bath Abbey and a few honoured guests to join her for luncheon, to meet Lord Dammler and set his feet on the path to righteousness. In the afternoon she requested his escort on a drive in the country to commune with nature and a widowed friend seventy years old, and at six o’clock it was back to Bath for a heavy dinner of mutton. The evening saw him taking her to a church discussion group on Dissenters. By eleven o’clock he was more than ready for bed. He felt as if he had swum to America and back.

On Monday a trip to the Pump Room was made by the Countess to set her up for the rigours of the week. It was also necessary for Clarence Elmtree. No one at all had seen them on Sunday, with Prudence hustling them into the carriage and home so fast. He was torn between being there early to make a good long visit, and entering late and causing a fuss. He opted for the former and drank two glasses of the foul sulphur water to keep his chest in shape till he got back to Knighton, who, over the few days, had become established as his physician. His advice was quoted on several complaints to people in Bath. He was just informing a Mrs. Plunkett of the efficacy of a certain paregoric draught when Lady Cleff and Lord Dammler came into the Pump Room.

Scanning the room Dammler's eyes stopped when he saw Clarence’s party. He bowed formally and smiled before sitting down with his cousin to partake of the water. Soon some elderly friends of the Countess had joined them and Dammler sat on staidly, conversing with them. Prudence didn’t see him smile once the entire time he was there. What a dull time he is having, yet he doesn’t bother coming to talk to us, she thought. In half an hour, she convinced her uncle it was time to go and look at her cartoon in the window again. It was necessary for them to pass the Dowager’s table to get out, and as they approached, Dammler arose to greet them, bowing to the ladies and shaking Elmtree’s hand. He begged the honour of presenting them to his cousin, which honour was granted.

The Dowager raised her lorgnette and examined them one by one, as if they were three indifferent specimens of Lepidoptera pinned on a board, said “Charmed” to Mrs. Mallow and Prudence, and allowed Clarence to shake three fingers briefly. She was in a particularly genial mood that day.

They were just turning to leave-no offer of joining the Pillar’s table was extended-when another gentleman seated across the room hastened towards them. He was of Dammler's approximate age and height, but slender and of fair complexion. Lady Cleff’s smile broadened as she spotted this addition to the group.

“Ah, Mr. Springer,” she said, offering him all four fingers and the thumb. “Dammler, here is someone who knows you, I believe. Just the very friend for you. I think you are dull with no companions but my old crones.”

A few stiff and stilted phrases were exchanged between the two old colleagues, giving a foretaste of how agreeable they found each other’s company. The Mallows and Mr. Elmtree made their farewells and left.

“I see you are anxious to be off, Mr. Springer,” the Dowager said coyly. “We shan’t detain you, but you must be sure to call. We will look forward to seeing you at Pulteney Street very soon.”

Springer fairly dashed off after the departing company, and Dammler was left with yet another obstacle in his wooing of Miss Mallow. A rival, one who had the advantage of a long acquaintance and an unblemished reputation.

He turned to his cousin. “Springer is Miss Mallow’s beau, I take it?”

“Yes, he is often with her. Usually escorts her home from the Pump Room. Truth to tell, I wish him success with her. She seems a nice enough sort of a girl, now that I have met her. Not forthcoming in the least. I had heard she was just a trifle fast-oh, not loose. I do not mean to imply she is loose. With a good solid husband like Springer she would be no poor addition to Bath society.”

This suggestion of Springer being considered as a husband for Prudence threw Dammler into alarm. “Surely they are not on the point of an engagement. Prudence- Miss Mallow-has not been here above two weeks.”

“It is a long-standing attachment. Quite romantic, really. Friends for years in Kent. It often happens that old friends met under different circumstances become more than friends. I think she might get him if she plays her cards well.”

This idea so appalled Dammler that he abandoned his plans of being circumspect and wearing the costume of a dull, respectable gentleman for a few weeks. He went that very afternoon to Laura Place and asked Prudence to drive out with him. In fact, he arrived just as she was leaving the luncheon table.

Her chagrin was possibly greater than his own. She had already given Springer permission to call that same afternoon. “I am busy this afternoon,” she said, in a stricken voice.

“Oh. I see,” he answered with sinking heart. “Busy, eh? Well, I had better leave you then.”

“Oh, no-that is, I do not go out until four o’clock. It is only a little after two o’clock. We have time for a little visit.”

Clarence was smiling and nodding in one corner, and Mrs. Mallow furrowing her brow across the room. There was no private study where they could pretend to be discussing literature, and the situation appeared hopeless.

“Would you like to go for a short drive?” Dammler asked, knowing it sounded absurd, as she had mentioned her outing was to be a drive.

“Yes, that sounds delightful,” she answered promptly, and went straight off to get her bonnet.

There was so much to be said between them, yet both were bereft of meaningful words. They mentioned the weather, the sights of Bath, even their respective states of health.

Sensing that his precious bit of time was slipping away, Dammler asked bluntly, “Are you angry with me for coming to Bath?”

“No, why should I be? You are free to roam as you like,” was her unencouraging reply. “You have been in London 'til now, I collect?”

“Yes.”

“How is Lady Melvine?”

“Very well. Murray also. I told him I would enquire how your book goes on.”

“I have written to Mr. Murray just recently.”

“He cannot have had your letter when I saw him last then.”

“No.”

After a quarter of an hour’s uninteresting conversation of this sort, they were on Milsom Street, and Dammler asked her if she would like to get down and walk a little. The outing was going so poorly that he feared he had lost her to Springer, but he didn’t want to hear it confirmed, so he did not ask.

As they strolled they passed the circulating library, and Dammler drew up to see her cartoon in the window.

“Your uncle will like this,” he said. “You might get that other shelf out of him yet.”

“Oh, now, with you borrowing all my books I scarcely have need of the two I have.”

“Have I been borrowing your books?” he asked, hoping to get back on the old footing with these joking references to old times.

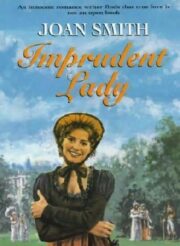

"Imprudent Lady / An Imprudent Lady" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Imprudent Lady / An Imprudent Lady". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Imprudent Lady / An Imprudent Lady" друзьям в соцсетях.