Before he took her home, he invited her to a play the next evening, but she was wary of going into public with him again alone and claimed a previous appointment. He took this in good part as coyness, and felt the time had come to begin distributing his largesse.

The next morning yet another arrangement of flowers arrived, and concealed among the stems was a blue velvet box. Miss Mallow was struck dumb, upon opening it, to see a fine set of matched diamonds sparkling at her. She lifted them out and beheld a necklace. Her first thought was that it was a mistake. The box had somehow been put in with her flowers by accident. She ran to her mother, asking if she should not go back to the flower stall and return them. Clarence had to be called in on such a momentous decision as this to give the male viewpoint.

“What would a set of diamonds be doing at the flower stall?” he asked reasonably.

“They must have been meant to go in some other arrangement of flowers,” Prudence suggested. “They are likely a wedding gift or some such thing. Will you come with me, Uncle? I dislike to go into the streets carrying anything so valuable, and we cannot send a footboy on such an errand.”

“That must certainly be the explanation,” her mother agreed, fingering the stones lovingly.

While they talked, Prudence opened the little card that accompanied the flowers, and her eyes widened. Mr. Seville had laboured long over a suitably discreet message to send along with his bribe and come up with the words, “Pray accept this small necklace as a token of my esteem, and an indication of my intentions.” She handed the card to her mother. “It is no mistake,” she said. “Mr. Seville sent the necklace.”

Mrs. Mallow had time to read half the message before Clarence had the card out of her hands. “The fellow is a rascal!” he charged angrily.

Mrs. Mallow retrieved the card and read the rest of it. “It is no such a thing, Clarence,” she answered. “See, he speaks of his ‘intentions.’ It is an engagement gift.”

“We are not engaged,” Prudence said, horrified. “Why, I scarcely know the man. It is ludicrous to speak of an engagement on such short acquaintance.”

Clarence was again examining the card. “You’re right, Wilma. ‘An indication of my intentions,’ he says. He means to have Prudence.

“I don’t mean to have him!” Prudence replied.

“Not have him? Nonsense,” Clarence declared. “He is a fine fellow. Knows everyone. Ho, what a joke it is, us thinking he meant it as an insult. He would not dare to insult Prue. He knows pretty well I am connected with Sir Alfred and Lord Dammler. Well, this will teach Dammler to shilly-shally around with his courting. Snapped right up under his nose. Serve him right.”

“Uncle, I do not mean to accept Mr. Seville or the necklace.”

He was deaf to her protests. “Wait until Mrs. Hering hears this. Her feather is dry.I’ll take her picture round to her myself this afternoon and tell her what my niece is up to. Real diamonds,” he said, opening the blue velvet box. “It is a pity I couldn’t paint them. I must do a portrait of Mr. Seville. Some little symbol of Seville being named after him can be slipped in. A corner of the old Gothic cathedral perhaps, or the Alcazar. I daresay I have a picture of it somewhere about the house. I might do him in costume as a grandee-Lawrence is always dressing his models up in costumes of some sort or other. I don’t like to satisfy him to copy his trick. No, I will do Mr. Seville in modern dress, with the Alcazar in the background, and a nice piece of gold in his hand. Gold paints up nicely.”

“I will return the necklace,” Prudence said.

Her mother regarded her in uncertainty. “It seems a pity, Prue. Can you not care for him? He seems a very nice gentlemanly sort of a man, so lively and good-natured. You are getting on…"

“No, Mama. I will not be bought.”

Clarence, holding the necklace to the light muttered to himself. "There’s yellow and orange in them. I never tried yellow and orange to do a diamond. And blue and green and purple. It’s a rainbow is what it is. A prism. There is the secret of doing a diamond! Come to the studio, Prue. We will paint you in the diamond necklace, with Seville in the background-the city I mean."

“I’m giving them back,” Prudence said, snatching them from his fingers.

“Think what you are about, Prue,” he warned. “You’ll never get another offer like this. The man is rich as Croesus. You’ll never have to write another word. Burning out your eyes with that scribbling… You will be dashing off to balls and coronations and Spain.”

“He is a mere commoner, Uncle,” Prudence reminded him, to mitigate the blow of her refusal.

“I daresay he is a marquis or some such thing-whatever sort of a handle they use in Spain, if the truth were known. They wouldn’t have named a city after him for nothing. On your honeymoon you ought to nip over to Seville and look into it. He has a Spanish look about him, now I come to think of it. The eyes are dark, and the face quite swarthy.”

“There will be no honeymoon.”

“And even if he ain’t,” Clarence rattled on, deaf to any drum but his own, “he can buy up a title. They are for sale if the pockets are plump enough. Everyone knows that. He might start off with a simple ‘Sir’ and work his way up to a lordship.”

“I am returning this necklace immediately,” Prudence said, and left with it in her hand.

Her mother rushed after her. “He will be calling today, after this. Wait and hear what he has to say, Prue. Think about it a little. Be wise, my dear. You were always so prudent before.”

“I am being prudent now, Mama. I do not wish to marry Mr. Seville. Indeed I do not. I don’t care for him in the least-in that way I mean.”

“My dear, you must not hope Dammler means to have you. He is quite above your touch. He thinks of you only as a friend. It is clear from his manner.”

Prudence looked aghast. She had not thought she was so transparent as that. “I think of him as a friend, too.”

“A little more than that on your side, I think,” her mother said gently. “I do not mean to force you. Such a thought would be quite repellent to me. You are all grown up now. You must do as you think best, but don’t be rash, my dear. Think of it a bit. It would be very fine to be independent-not to have to worry about the future. We are very comfortable now, but Clarence will not live forever. Sooner or later his son George will be taking over, and he will not want to be saddled with us.”

Prudence did not change her mind, but she agreed to think about it before acting. Every word her mama said was true. They faced a bleak future of comparative poverty. It could be removed by her accepting an offer from a gentleman she did not actively dislike-one who could and would give her everything she wanted, and more importantly, would let her give Mama what she wanted. But the price was too high. She could not consider it independence to be bound leg and wing to Mr. Seville. She did not admit to any other reason for refusing him in her ruminations.

In the afternoon he called, and to remove him from Uncle Clarence’s congratulations, she grabbed her wrap and went out with him.

“You had my little gift?” he asked, as soon as the coach bowled away from the house.

She had it right in her reticule to return. “I cannot accept it, Mr. Seville.”

“It is a mere bauble. When the matter is settled to our mutual satisfaction, I will give you a real necklace. I am not a skint, Miss Mallow. You will not find me clutch-fisted.”

“I know I would not. You are very generous, Mr. Seville, but I cannot feel we would suit.”

“I know I am not clever like you, but you would be able to smarten me up if you felt it worth your while. We would be happy together. A nice apartment-house if you wish-either in the city or country. All would be to your orders.”

She repined, but she did not weaken a whit. “No, really. I think of you only as a friend. I had not thought of any closer association.”

“If it’s money that worries you…"

“No, it’s not that. I know you are wealthy-generous.”

“A cash settlement beforehand. Everything in order right and tight.”

“No, please, it sounds so very mercenary. I do not wish to haggle over it. I am flattered-honoured, but I cannot accept your offer.”

“Is it your family that worries you?”

“Oh, no, they thought it a very good thing. They were not in the least averse. It is quite my own decision.”

This easy capitulation of the family bothered him. “I felt your uncle would not mind, but mothers sometimes throw a rub in the way.”

“Mama is anxious to see me settled. She worries about the future.”

“I would take good care of you.”

“I cannot feel it would answer.” She took the velvet box from her reticule and handed it to him.

“Keep it,” he said magnanimously. “I don’t despair yet. I will have at you again, Miss Mallow. I don’t give up easily.”

“No, it would be improper in me to keep it when I don’t mean to marry you,” she said, and shoved it to him.

Looking with downcast eyes at the box, she did not see his eyes start at the dread word “marry.” He could scarcely believe his ears. No mention had been made of marriage. What had she got into her head-to think he would marry a little nobody without a connection in the world? He feared Miss Mallow was making sport of him. But when she did finally look up, the innocent lustre of her eyes disabused him of that idea. He felt weak, and very fortunate indeed to have escaped so easily from his unprecedented predicament. Only think if she had accepted! He took the box without a word and stuck it into his pocket.

“I expect you would like to go home?” he said a moment later.

She nodded. "I'm sorry,” she said, before she descended from the coach. “I hope we may continue friends?”

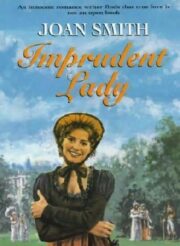

"Imprudent Lady / An Imprudent Lady" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Imprudent Lady / An Imprudent Lady". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Imprudent Lady / An Imprudent Lady" друзьям в соцсетях.