“What will you do if I don’t—and you are?”

“I don’t know yet. But it won’t be pretty.” Her smile made the whole aggravating day worth it.

She headed to the bed with the book and paused. “I forgot. I need to put on my night rail. I’ll feel cozier.”

“I’ll get it,” he said, and pulled open several drawers before he found one.

She put her beloved book aside and took the garment. Then looked at him and bit her lip.

“I won’t look.” He turned his back and crossed his arms.

“Thank you,” she said.

It took a good few minutes for her to prepare herself—it seemed like a lifetime to him. He was tempted—sorely tempted—to turn around and peek.

“Done,” she eventually said.

She was already tucked in beneath the covers. The lamp on the bedside table sent a lovely glow over her features.

She held the book open. “I’m waiting for you.”

Oh. He’d been caught doing absolutely nothing but staring and admiring. He felt as if he were a student who’d been reprimanded by a schoolteacher. A very tempting schoolteacher.

“Please,” she said. “Make yourself more comfortable.”

“I’ve no modest way to disrobe,” he told her, and yanked his shirt over his head, exposing his chest and belly.

He had to restrain a laugh when he saw her eyes widen.

“You will keep your breeches on, won’t you?” she asked.

“Of course.” He strolled around the bed to the far side, lifted the quilt, and got into bed with her.

Immediately, there was delicious tension. She tried her best to hold on to the book and pretend that everything was all business, but he knew better. Her cheeks had flushed a lovely rose color, and she wouldn’t quite look at him.

“Daisy?” he whispered.

She turned to look at him. “Yes?”

“Read to me,” he said.

Her eyes lit with both relief and anticipation. “You’re going to like this. Poems by Robert Burns. He’s beloved by all of Scotland.”

“Is that so?” Charlie settled himself back on his pillow, his hands folded behind his head, and listened to her read a poem called “To a Mouse”:

Wee, sleekit, cow’rin’, tim’rous beastie,

O what a panic’s in thy breastie,

Thou need na start awa sae hasty,

Wi’ bickering brattle!

I wad be laith to rin an’ chase thee,

Wi’ murd’ring pattle!

She took a breath, but he interrupted her before she could go on. “I’m sorry,” he said, “but … I have no idea what you just said.”

“Oh!” She leaned closer so he could see the words. “It’s about a mouse turned up by a plow—”

“Really.” He was enjoying the closeness, her shoulder propped against his.

“And the farmer is feeling awfully guilty for destroying its home,” she went on.

“Is that so?” He lifted a lock of hair off her shoulder and put it behind her ear.

“And—” She looked at him, and her brows lowered. “You’re not really listening, are you?”

“Oh, I am,” he said. “Please go on.”

He lay back on his pillows again and didn’t interrupt her once. He already knew the poem by heart. So when she got to the last verse, he recited along with her, his eyes on the ceiling.

When they both said the last word together, she slammed the book shut.

He looked over at her and enjoyed seeing her mouth a big O. “You already knew it?”

“Yes,” he replied in his driest manner. “And I hated it. I hated it with a passion.”

“Did you.” She narrowed her eyes at him.

“Yes. So you’re going to have to punish me.”

She closed the book with a sigh. “I adore that poem. I’d like to meet that farmer. He seems so wise and kind.”

“What about the punishment? Are you a woman of your word or not?”

She merely scooted away from him. “I wonder if Robert Burns really did turn up a mouse—”

“‘The best-laid schemes o’ mice and men gang aft a-gley,’” said Charlie with a sigh. “No matter how well you plan, something can go wrong. Leave it to a poet to couch a harsh truth in such a lyrical way.”

“Exactly.” Daisy scooted back in his direction and turned on her side to face him. “But he’s right. You just never know what’s around the corner.”

“It’s what makes life exciting.”

“Yes,” she said. “I’ve always felt my life was meant to be exciting. Even though I live here, far away from everything.”

“I’ll bet you look out the window of your little turret in Castle Vandemere and dream big dreams.”

“I do. How did you know?”

He smiled. “I know you, Daisy Montgomery. And I like who I see.”

There was a beat of silence. Her fairy blue eyes gleamed with something soft and vulnerable. Something hopeful. And something inviting.

Charlie felt as if he were being pulled by some inexorable force toward her. She moved an inch toward him, and then their lips met.

“Charlie,” she whispered. “I like you, too. Very much.”

He lifted himself up, scooped her in his arms, and gazed down at her.

She gifted him with a shy smile.

And then he kissed her—madly, passionately.

It was better than being at the finest opera with the chorus going and the big drums booming, violins flying up and down the scale, the lead tenor singing his heart out to the lead soprano, and the lead soprano singing back—and the whole audience struck dumb with wonder and anticipation, the applause surging … surging into a great crescendo with cymbals crashing.

And that was only the kissing part. Charlie had never, ever felt so exhilarated by mere kissing.

But he was kissing her.

Daisy.

The girl who’d made everything different. And not because she was a Highland lass. Not because her voice was like buzzing bumblebees. Nor was it because she had an outlandish sense of adventure.

It was because of how she looked at him. It was as if she could see deep into his soul, past the bad Charlie to the real Charlie—

And the real Charlie she saw wasn’t a shining knight, thank God.

No, the real Charlie was the same as the bad Charlie.

But she liked him anyway.

It was such a relief … he didn’t have to pretend to be someone else. Not that he ever thought that was what he’d been doing, but now he saw that he had. Hiding from his parents his title of Impossible Bachelor. Earning loads of money to impress the world with his business acumen since he’d not been able to go to the Wars—thanks to being the heir who wasn’t allowed to die.

With Daisy, he could let go.

“Let go with me,” he said into her ear.

“I want to,” she murmured against his jaw.

He closed his eyes, wishing with all his heart he could bed her. But he couldn’t.

How was he to let go?

He decided not to think about it, and to focus on her, the delightful, sweet-smelling young lady melding her body to his.

Heaven on earth … merely sliding his hand down her arm, over every swell and valley, until their fingers clashed and clung.

“This time it’s your day,” Daisy said.

They were side by side.

“No,” he insisted. “It’s yours.”

She shook her head and got that very obstinate look in her eye that he well recognized.

And next thing he knew, she was pressing her hand on his hard length, caressing him through his breeches, all the while kissing his neck and then his chest. He groaned at the sensations coursing through him when she mouthed his nipple, sucking tenderly.

But then she stopped. “I want to take off your breeches,” she said.

“Well, then.” He was amused by her forthright manner. “Go right ahead.”

She got to work, fumbling with the flap. He did his best to help her, but she kept shooing his hands away. She was so busy that when she finally had success, the effects of what she’d accomplished appeared to hit her like a ton of bricks.

“Oh, dear,” she said, and looked from his privates to his face and back again to his nether regions.

He shrugged.

“You’re magnificent,” she said. “Like David.”

“The statue?”

“No, David the baker’s son.” She giggled. “Of course I meant David the statue. I’ve seen illustrations.”

“Ah. Well, it’s your turn to look like Bernini’s Daphne.”

Without a word, she pulled off her night rail, exposing her beautiful naked body to the lamplight. “Was she naked?” she whispered.

“Uh-huh,” Charlie said back, and pulled her on top of him.

Daisy closed her eyes and clung to him.

“Are you all right?” he asked her.

She nodded.

He lifted her chin. “Are you sure?”

She nodded again. “It feels so … perfect.”

“It can feel even more perfect, as you know. But now’s a good time to remind ourselves of something.”

“What?”

“It can feel even more perfect than the perfect you felt on the Stone Steps.”

She groaned as if she couldn’t bear to hear it. “Really?”

“This is good news,” he said, “usually. But not for us. We can’t go to that particularly perfect place. It would mean I’d compromised you so completely, there would be no turning back. We’d have to marry.”

“Gad,” she said.

“It’s how babies are made, and I’m afraid neither of us is ready for that.”

“No, indeed.”

“But we can still enjoy ourselves, and each other.”

“The other perfects suit me very well,” she said gamely.

“Good,” he said. “Because I’m going to make you feel perfect again, but this time you won’t be sitting up on some stone steps, you’ll be flung back against some lovely pillows.”

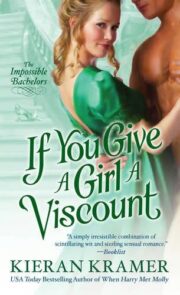

"If You Give A Girl A Viscount" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "If You Give A Girl A Viscount". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "If You Give A Girl A Viscount" друзьям в соцсетях.