“No. I’m fine. Mom needs me. Dad’s kind of freaking out, though.”

“Did he puke yet?” Henry asked, sitting back down on the couch. I laughed, but then saw from his face that he was serious.

“He threw up when you were coming. Almost fainted on the floor. Not that I can blame him. But the dude was a mess, the doctors wanted to kick him out. . said they were going to if you didn’t come out within a half hour. That got your mom so pissed off she pushed you out five minutes later.” Henry smiled, leaning back into the sofa. “So the story goes. But I’ll tell you this: He cried like a motherfucking baby when you were born.”

“I’ve heard that part.”

“Heard what part?” Dad asked breathlessly. He grabbed the bag from Henry. “Taco Bell, Henry?”

“Dinner of champions,” Henry said.

“It’ll do. I’m starving. It’s intense in there. Got to keep up my strength.”

Henry winked at me. Dad pulled out a burrito and offered one to me. I shook my head. Dad had started unwrapping his meal when Mom let out a growl and then started screaming at the midwife that she was ready to push.

The midwife poked her head out the door. “I think we’re getting close, so maybe you should save dinner for later,” she said. “Come on back.”

Henry practically bolted out the front door. I followed Dad into the bedroom where Mom was sitting now, panting like a sick dog. “Would you like to watch?” the midwife asked Dad, but he just swayed and turned a pale shade of green.

“I’m probably better up here,” he said, grasping Mom’s hand, which she violently shook off.

No one asked me if I wanted to watch. I just automatically went to stand next to the midwife. It was pretty gross, I’ll admit. Lots of blood. And I’d certainly never seen my mom so full-on frontal before. But it felt strangely normal for me to be there. The midwife was telling Mom to push, then hold, then push. “Go baby, go baby, go baby go,” she chanted. “You’re almost there!” she cheered. Mom looked like she wanted to smack her.

When Teddy slid out, he was head up, facing the ceiling, so that the first thing he saw was me. He didn’t come out squalling like you see on TV. He was just quiet. His eyes were open, staring straight at me. He held my gaze as the midwife suctioned out his nose. “It’s a boy,” she shouted.

The midwife put Teddy on Mom’s belly. “Do you want to cut the cord?” she asked Dad. Dad waved his hands no, too overcome or nauseous to speak.

“I’ll do it,” I offered.

The midwife held the cord taut and told me where to cut. Teddy lay still, his gray eyes wide open, still staring at me.

Mom always said that it was because Teddy saw me first, and because I cut his cord, that somewhere deep down he thought I was his mother. “It’s like those goslings,” Mom joked. “Imprinting on a zoologist, not the mama goose, because he was the first one they saw when they hatched.”

She exaggerated. Teddy didn’t really think I was his mother, but there were certain things that only I could do for him. When he was a baby and going through his nightly fussy period, he’d only calm down after I played him a lullaby on my cello. When he started getting into Harry Potter, only I was allowed to read a chapter to him every night. And when he’d skin a knee or bump his head, if I was around he would not stop crying until I bestowed a magic kiss on the injury, after which he’d miraculously recover.

I know that all the magic kisses in the world probably couldn’t have helped him today. But I would do anything to have been able to give him one.

10:40 P.M

I run away.

I leave Adam, Kim, and Willow in the lobby and I just start careening through the hospital. I don’t realize I’m looking for the pediatric ward until I get there. I tear through the halls, past rooms with nervous four-year-olds sleeping restlessly before tomorrow’s tonsillectomies, past the neonatal ICU with babies the size of fists, hooked up to more tubes than I am, past the pediatric oncology unit where bald cancer patients sleep under cheerful murals of rainbows and balloons. I’m looking for him, even though I know I won’t find him. Still, I have to keep looking.

I picture his head, his tight blond curls. I love to nuzzle my face in those curls, have done since he was a baby. I kept waiting for the day when he’d swat me away, say “You’re embarrassing me,” the way he does to Dad when Dad cheers too loudly at T-ball games. But so far, that hadn’t happened. So far, I’ve been allowed constant access to that head of his. So far. Now there is no more so far. It’s over.

I picture myself nuzzling his head one last time, and I can’t even imagine it without seeing myself crying, my tears turning his blond curlicues straight.

Teddy is never going to graduate from T-ball to baseball. He’s never going to grow a mustache. Never going to get into a fistfight or shoot a deer or kiss a girl or have sex or fall in love or get married or father his own curly-haired child. I’m only ten years older than him, but it’s like I’ve already had so much more life. It is unfair. If one of us should have been left behind, if one of us should be given the opportunity for more life, it should be him.

I race through the hospital like a trapped wild animal. Teddy? I call. Where are you? Come back to me!

But he won’t. I know it’s fruitless. I give up and drag myself back to my ICU. I want to break the double doors. I want to smash the nurses’ station. I want it all to go away. I want to go away. I don’t want to be here. I don’t want to be in this hospital. I don’t want to be in this suspended state where I can see what’s happening, where I’m aware of what I’m feeling without being able to actually feel it. I cannot scream until my throat hurts or break a window with my fist until my hand bleeds, or pull my hair out in clumps until the pain in my scalp overcomes the one in my heart.

I’m staring at myself, at the “live” Mia now, lying in her hospital bed. I feel a burst of fury. If I could slap my own lifeless face, I would.

Instead, I sit down in the chair and close my eyes, wishing it all away. Except I can’t. I can’t concentrate because there’s suddenly so much noise. My monitors are blipping and chirping and two nurses are racing toward me.

“Her BP and pulse ox are dropping,” one yells.

“She’s tachycardic,” the other yells. “What happened?”

“Code blue, code blue in Trauma,” blares the PA.

Soon the nurses are joined by a bleary-eyed doctor, rubbing the sleep out of his eyes, which are ringed by deep circles. He yanks down the covers and lifts my hospital gown. I’m naked from the waist down, but no one notices these things here. He puts his hands on my belly, which is swollen and hard. His eyes widen and then narrow into slits. “Abdomen’s rigid,” he says angrily. “We need to do an ultrasound.”

Nurse Ramirez runs to a back room and then wheels out what looks like a portable laptop with a long white attachment. She squirts some jelly on my stomach, and the doctor runs the attachment over my stomach.

“Damn. Full of fluid,” he says. “Patient had surgery this afternoon?”

“A splenectomy,” Nurse Ramirez replies.

“Could be a missed blood vessel that wasn’t cauterized,” the doctor says. “Or a slow leak from a perforated bowel. Car accident, right?”

“Yes. Patient was medevaced in this morning.”

The doctor flips through my chart. “Doctor Sorensen was her surgeon. He’s still on call. Page him, get her to the OR. We need to get inside and find out what’s leaking, and why, before she drops any further. Jesus, brain contusions, collapsed lung. This kid’s a train wreck.”

Nurse Ramirez shoots the doctor a dirty look, as if he had just insulted me.

“Miss Ramirez,” the grumpy nurse at the desk scolds. “You have patients of your own to deal with. Let’s get this young woman intubated and transferred to the OR. That will do her more good than all this dillydallying around!”

The nurses work rapidly to detach the monitors and catheters and run another tube down my throat. A pair of orderlies rush in with a gurney and heave me onto it. I’m still naked from the waist down as they hustle me out, but right before I reach the back door, Nurse Ramirez calls, “Wait!” and then gently closes the hospital gown around my legs. She taps me three times on the forehead with her fingers, like it’s some kind of Morse code message. And then I’m gone into the maze of hallways leading toward the OR for another round of cutting, but this time I don’t follow myself. This time I stay behind in the ICU.

I am starting to get it now. I mean, I don’t totally fully understand. It’s not like I somehow commanded a blood vessel to pop open and start leaking into my stomach. It’s not like I wished for another surgery. But Teddy is gone. Mom and Dad are gone. This morning I went for a drive with my family. And now I am here, as alone as I’ve ever been. I am seventeen years old. This is not how it’s supposed to be. This is not how my life is supposed to turn out.

In the quiet corner of the ICU I start to really think about the bitter things I’ve managed to ignore so far today. What would it be like if I stay? What would it feel like to wake up an orphan? To never smell Dad smoke a pipe? To never stand next to Mom quietly talking as we do the dishes? To never read Teddy another chapter of Harry Potter? To stay without them?

I’m not sure this is a world I belong in anymore. I’m not sure that I want to wake up.

I’ve only ever been to one funeral in my life and it was for someone I hardly knew.

I might have gone to Great-Aunt Glo’s funeral after she died of acute pancreatitis. Except her will was very specific about her final wishes. No traditional service, no burial in the family plot. Instead, she wanted to be cremated and have her ashes scattered in a sacred Native American ceremony somewhere in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Gran was pretty annoyed by that, by Aunt Glo in general, who Gran said was always trying to call attention to how different she was, even after she was dead. Gran ended up boycotting the ash scattering, and if she wasn’t going, there was no reason for the rest of us to.

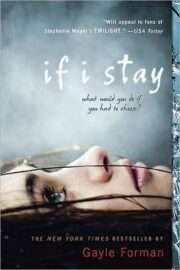

"If I Stay" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "If I Stay". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "If I Stay" друзьям в соцсетях.