That gives me the guts to go to him now. Or rather to me, to the ICU, which is where I know he will want to go. Adam knows Gran and Gramps and the cousins, and I imagine he’ll join the waiting-room vigil later. But right now he’s here for me.

Back in the ICU time stands still as always. One of the surgeons who worked on me earlier — the one who sweated a lot and, when it was his turn to pick the music, blasted Weezer — is checking in on me.

The light is dim and artificial and kept to the same level all the time, but even so, the circadian rhythms win out and a nighttime hush has fallen over the place. It is less frenetic than it was during the day, like the nurses and machines are all a little tired and have reverted to power-save mode.

So when Adam’s voice reverberates from the hallway outside the ICU, it really wakes everyone up.

“What do you mean I can’t go in?” he booms.

I make my way across the ICU, standing just on the other side of the automatic doors. I hear the orderly outside explain to Adam that he is not allowed in this part of the hospital.

“This is bullshit!” Adam yells.

Inside the ward, all the nurses look toward the door, their heavy eyes wary. I am pretty sure they’re thinking: Don’t we have enough to deal with inside without having to calm down crazy people outside? I want explain to them that Adam isn’t crazy. That he never yells, except for very special occasions.

The graying middle-aged nurse who doesn’t attend to the patients but sits by and monitors the computers and phones, gives a little nod and stands up as if accepting a nomination. She straightens her creased white pants and makes her way toward the door. She’s really not the best one to talk to him. I wish I could warn them that they ought to send Nurse Ramirez, the one who reassured my grandparents (and freaked me out). She’d be able to calm him down. But this one is only going to make it worse. I follow her through the double doors where Adam and Kim are arguing with an orderly. The orderly looks at the nurse. “I told them they’re not authorized to be up here,” he explains. The nurse dismisses him with the wave of a hand.

“Can I help you, young man?” she asks Adam. Her voice sounds irritated and impatient, like some of Dad’s tenured colleagues at school who Dad says are just counting the days till retirement.

Adam clears his throat, attempting to pull himself together. “I’d like to visit a patient,” he says, gesturing toward the doors blocking him from the ICU.

“I’m afraid that’s not possible,” she replies.

“But my girlfriend, Mia, she’s—”

“She’s being well cared for,” the nurse interrupts. She sounds tired, too tired for sympathy, too tired to be moved by young love.

“I understand that. And I’m grateful for it,” Adam says. He’s trying his best to play by her rules, to sound mature, but I hear the catch in his voice when he says: “I really need to see her.”

“I’m sorry, young man, but visitations are restricted to immediate family.”

I hear Adam gasp. Immediate family. The nurse doesn’t mean to be cruel. She’s just clueless, but Adam won’t know that. I feel the need to protect him and to protect the nurse from what he might do to her. I reach for him, on instinct, even though I cannot really touch him. But his back is to me now. His shoulders are hunched over, his legs starting to buckle.

Kim, who was hovering near the wall, is suddenly at his side, her arms encircling his falling form. With both arms locked around his waist, she turns to the nurse, her eyes blazing with fury. “You don’t understand!” she cries.

“Do I need to call security?” the nurse asks.

Adam waves his hand, surrendering to the nurse, to Kim. “Don’t,” he whispers to Kim.

So Kim doesn’t. Without saying another word, she hoists his arm around her shoulder and shifts his weight onto her. Adam has about a foot and fifty pounds on Kim, but after stumbling for a second, she adjusts to the added burden. She bears it.

Kim and I have this theory that almost everything in the world can be divided into two groups.

There are people who like classical music. People who like pop. There are city people. And country people. Coke drinkers. Pepsi drinkers. There are conformists and free-thinkers. Virgins and nonvirgins. And there are the kind of girls who have boyfriends in high school, and the kind of girls who don’t.

Kim and I had always assumed that we both belonged to the latter category. “Not that we’ll be forty-year-old virgins or anything,” she reassured. “We’ll just be the kinds of girls who have boyfriends in college.”

That always made sense to me, seemed preferable even. Mom was the sort of girl who had had boyfriends in high school and often remarked that she wished she hadn’t wasted her time. “There’s only so many times a girl wants to get drunk on Mickey’s Big Mouth, go cow-tipping, and make out in back of a pickup truck. As far as the boys I dated were concerned, that amounted to a romantic evening.”

Dad on the other hand, didn’t really date till college. He was shy in high school, but then he started playing drums and freshman year of college joined a punk band, and boom, girlfriends. Or at least a few of them until he met Mom, and boom, a wife. I kind of figured it would go that way for me.

So, it was a surprise to both Kim and me when I wound up in Group A, with the boyfriended girls. At first, I tried to hide it. After I came home from the Yo-Yo Ma concert, I told Kim the vaguest of details. I didn’t mention the kissing. I rationalized the omission: There was no point getting all worked up about a kiss. One kiss does not a relationship make. I’d kissed boys before, and usually by the next day the kiss had evaporated like a dewdrop in the sun.

Except I knew that with Adam it was a big deal. I knew from the way the warmth flooded my whole body that night after he dropped me off at home, kissing me once more at my doorstep. By the way I stayed up until dawn hugging my pillow. By the way that I could not eat the next day, could not wipe the smile off my face. I recognized that the kiss was a door I had walked through. And I knew that I’d left Kim on the other side.

After a week, and a few more stolen kisses, I knew I had to tell Kim. We went for coffee after school. It was May but it was pouring rain as though it were November. I felt slightly suffocated by what I had to do.

“I’ll buy. You want one of your froufrou drinks?” I asked. That was another one of the categories we’d determined: people who drank plain coffee and people who drank gussied-up caffeine drinks like the mint-chip lattes Kim was so fond of.

“I think I’ll try the cinnamon-spice chai latte,” she said, giving me a stern look that said, I will not be ashamed of my beverage selection.

I bought us our drinks and a piece of marionberry pie with two forks. I sat down across from Kim, running the fork along the scalloped edge of the flaky crust.

“I have something to tell you,” I said.

“Something about having a boyfriend?” Kim’s voice was amused, but even though I was looking down, I could tell that she’d rolled her eyes.

“How’d you know?” I asked, meeting her gaze.

She rolled her eyes again. “Please. Everyone knows. It’s the hottest gossip this side of Melanie Farrow dropping out to have a baby. It’s like a Democratic presidential candidate marrying a Republican presidential candidate.”

“Who said anything about marrying?”

“I’m just being metaphoric,” Kim said. “Anyhow, I know. I knew even before you knew.”

“Bullshit.”

“Come on. A guy like Adam going to a Yo-Yo Ma concert? He was buttering you up.”

“It’s not like that,” I said, though of course, it was totally like that.

“I just don’t see why you couldn’t tell me sooner,” she said in a quiet voice.

I was about to give her my whole one-kiss-not-equaling-a-relationship spiel and to explain that I didn’t want to blow it out of proportion, but I stopped myself. “I was afraid you’d be mad at me,” I admitted.

“I’m not,” Kim said. “But I will be if you ever lie to me again.”

“Okay,” I said.

“Or if you turn into one of those girlfriends, always ponying around after her boyfriend, and speaking in the first-person plural. ‘We love the winter. We think Velvet Underground is seminal.’”

“You know I wouldn’t rock-talk to you. First-person singular or plural. I promise.”

“Good,” Kim replied. “Because if you turn into one of those girls, I’ll shoot you.”

“If I turn into one of those girls, I’ll hand you the gun.”

Kim laughed for real at that, and the tension was broken. She popped a hunk of pie into her mouth. “How did your parents take it?”

“Dad went through the five phases of grieving — denial, anger, acceptance, whatever — in like one day. I think he’s more freaked out that he is old enough to have a daughter who has a boyfriend.” I paused, took a sip of my coffee, letting the word boyfriend rest out in the air. “And he claims he can’t believe that I’m dating a musician.”

“You’re a musician,” Kim reminded me.

“You know, a punk, pop musician.”

“Shooting Star is emo-core,” Kim corrected. Unlike me, she cared about the myriad pop musical distinctions: punk, indie, alternative, hard-core, emo-core.

“It’s mostly hot air, you know, part of his whole bow-tie-Dad thing. I think Dad likes Adam. He met him when he picked me up for the concert. Now he wants me to bring him over for dinner, but it’s only been a week. I’m not quite ready for a meet-the-folks moment yet.”

“I don’t think I’ll ever be ready for that.” Kim shuddered at the thought of it. “What about your mom?”

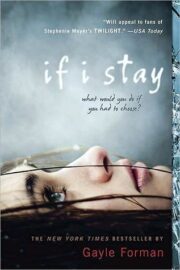

"If I Stay" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "If I Stay". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "If I Stay" друзьям в соцсетях.