The ladies gaped then nodded in anticipation of that delight. Mr. Waldon’s brow creased.

Mrs. Biddycock began reading anew. The news was mostly about people Teresa had never heard of and she attended with half an ear. Her father’s oblique warning commanded her thoughts.

She had no real justification for not marrying Mr. Waldon. And there was no guarantee that another suitor would ever present himself to her in Harrows Court Crossing. She would be forced to content herself with second-hand stories of Annie’s escapades with stable hands and farm lads, and she would spend the rest of her life attending to her mother’s imagined ailments.

“‘. . . Scottish earl,’” Mrs. Biddycock read. “‘I vow, Fanny, it will be a miracle if he finds husbands for even one of those half sisters. His Dark and Scandalous past is whispered in drawing rooms throughout town. His sisters are all hoydens and thoroughly unsuitable for polite company. But I shan’t write a word more about them!’” Teresa sat bolt upright. Scottish earl?

“‘Except to say,’” Mrs. Biddycock continued, “‘that my Henrietta will not attend any event at which we might encounter that heathen brood. If those girls should enter a drawing room to call when we are already there, we will depart at once. Do not mistake me, Fanny: If he were an English earl with one or even perhaps two unruly sisters, I would allow Henrietta to make their acquaintance. An earl is not to be sniffed at. But an impoverished Scotsman with seven sisters to wed in a single season is positively scandalous and I shan’t have any of it, unless perhaps one of them were to invite my Henrietta to tea.’” Teresa’s mouth was entirely dry. There could not be more than one Scottish earl with seven unwed half sisters. And now he was in London.

It was too wonderful!

“Oh, dear,” she said, leaping up. “I seem to have left my kerchief in the shop. I am terribly sorry to dash away like this, Mrs. Biddycock, but I really must retrieve it before it is carried away by a strong gust of wind or perhaps a sudden flood.”

Another lady giggled. “Miss Finch-Freeworth, you are always so amusing.”

“Isn’t she? The dear girl.” Mrs. Biddycock smiled approvingly and rustled pages.

Teresa escaped.

Mr. Waldon came after her.

“Miss Finch-Freeworth, your abrupt departure concerns me.” He strode alongside her across the high street muddied by the morning’s rain. “Your kerchief must be especially dear to you to cause you to hasten so.”

“Yes, I am ever so attached to—”

“And here it is, in your pocket all along.” His grip on her elbow forced her to halt. He plucked at the corner of the kerchief poking out of her pocket and drew it forth. “You must have mistaken yourself, but I am happy to restore to you peace of mind.”

No one else ever chastised her for her fibs. But Mr. Waldon had no humor in him, and thinking of marrying him weighed on her insides as if she had swallowed Robert Smith’s anvil.

“Silly me,” she said brightly, and detached herself from his grasp. “My head is all aflutter. I will shortly be departing for London, you see, and have so many tasks to do before I leave that my wits are quite scattered.”

“London? I had not heard of this.”

“Oh, yes. Within the sennight.” She had no travel plans. “My dear friend Mrs. Yale has invited me for a visit.” Diantha Yale had done no such thing. No doubt she was now with her adoring husband on their estate in Wales, dandling her infant on her knee by day and by night doing as often as possible what one did to make more infants. Mr. and Mrs. Yale were very happily married.

“But why do you go to London,” Mr. Waldon said, “when you have everything you wish here?”

He didn’t know anything of her wishes. But his face looked a bit like his bleached cravat now and it gave her pause. She placed her hand on his arm.

“Are you unwell, sir?”

He frowned at her hand. “I am well enough,” he said stiffly. “I only wonder that you would be comfortable leaving your mother at this time, given her illness.”

Fabricated illness. “She is not alone. She has Papa, of course. And Freddie has been sent down from school again.” This time it was for racing chickens in the chancery, which was so wonderfully the truth that she simply could not invent anything better. “He quite dotes on her.”

Aha! Freddie had told her at breakfast this morning that their eldest brother, Tobias, had just posted up to London. She would write to both Toby and Diantha, and hope that one of them would be in town. If not, she would force herself upon Aunt Hortensia and steal at least a few days in town before her aunt informed her parents and her father fetched her home.

She started up the street again.

Mr. Waldon kept pace with her. “Allow me to escort you home.”

“It is but a mile, and I do know the way.” She smiled to ease the sting of rejection. She needn’t have. He was constitutionally unable to recognize rejection.

“I have a matter of great importance which I wish to discuss with your father,” he said formally.

Dread. More panic. This time speeding through her veins like tiny daggers fashioned of the sorts of shards of ice that one found on windowsills in January.

“You will not find Papa at home, I’m afraid. He went shooting with Freddie this morning.” Dear Lord in heaven, let it be so.

Mr. Waldon frowned again and fixed her with a challenging regard. “Then I will return later.” He extended his hand for her to shake. “Good day, Miss Finch-Freeworth.” His palm was smooth and cool, his fingers long and they wrapped around her hand as if they would choke her.

He walked toward the parsonage, his back as rigid as the bell tower. Her stomach twisted in knots.

Mrs. Elijah Waldon.

It simply could not be.

She had an active imagination, but she had few illusions about herself.

She was not a noblewoman nor was she stunningly beautiful or an heiress.

She was not a fit bride for an earl, even an impoverished earl. But she had the memory of a single, longing gaze and now a great deal of determination and a measure of desperation as well.

She would go to London. She would find him. They would share another longing gaze. And she would finally have her kiss.

After that, if she were condemned to spend the remainder of her days in Harrows Court Crossing as the wife of a man she did not like, at least she would have the comfort of knowing she had burned hot and bright for one glorious moment.

2

Sunlight peeked through the smudged windowpane, warming the Indian cotton stretched over his shoulders. But Duncan, seventh Earl of Eads, did not move to draw the drapes or open his eyes to appreciate the weather. It mattered nothing to him if the London day shone or fogged or rained. Nor did it concern him if the sounds issuing from the street below his flat were the clatter of hooves and carriage wheels or the shouts of street vendors.

All had fallen away, the present world a vanishing shadow only. With eyes closed, back straight, and legs crossed, he remained still, seeking his center.

Deep within, in harmony and acceptance with all the creatures of the universe, peace awaited him. Like the petals of a flower, held close yet ready to spread with the touch of the morning sun, the core of his being—

“Lily! What’ve ye done wi’ ma pink ribbon?”

“I’ve no touched yer silly ribbon, Effie.”

“I’ll pull out yer hair if ye’ve ruined it.”

The swish of skirts.

Duncan slowly drew air into his lungs with the power of the muscles in his abdomen.

Slippered footsteps.

“If ye havena got it, then who has?”

“Mebbe ye lost it when ye stopped to flirt wi’ those soldiers?”

“I didna flirt.” Giggle. “I chatted.”

In tiny increments, Duncan released the breath, holding steady to his concentration, steady and still and—

“Aye, ye flirted. Deny it if ye will, but I’ll no be believing ye.”

Another giggle. “There be no harm in flirting, Lily. ’Tis interesting.”

“If yer wishing for something interesting, ye might open a wee book once in a while.” Creak of a chair. Flutter of a page turning. “Both o’ ye.”

“Then we wouldna need the ribbons, nou, would we, Abigail?” Laughter.

Breathe in. Slow, steady, smooth—

“Moira?” Firm strides between the parlor and bedchamber. “What did ye do wi’ the bill from the fabric shop yesterday?”

“We’d do better to be storing up prayers than dresses to help us all find husbands, Sorcha.”

Slow breaths. Seeking serenity. Seeking peace. Breaths as light as feathers yet deep as—

“No one asked ye, Elspeth, so keep yer sermons to yerself.”

“Confess, Lily.” Dainty toe tapping. “Ye hid ma ribbon.”

“I didna, I tell ye. Did I, Una?”

“Dinna drag me into yer disputes.” Chuckle. “I’ve no got the talent for it.”

“Moira, the bill?”

“What’re ye reading anyway, Abby?”

“Byron, that immoral—”

“Byron’s poetry isna immoral, Elspeth. ’Tis romantic.” Waft of fragrance.

“Here be the bill, Sorcha. I sewed the sleeves this morn.”

“Thank ye, Moira.”

Breathe.

“Ma pink ribbon!”

“Told ye I didna take it.”

Deeper.

“Ye’d best stow it away till ye’ve guid cause to wear it, Effie.” Firm steps.

“There willna be new ribbons or dresses or anything else—”

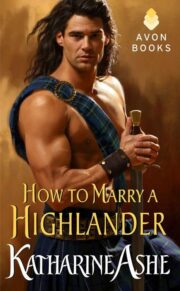

"How to Marry a Highlander" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "How to Marry a Highlander". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "How to Marry a Highlander" друзьям в соцсетях.