"Ella's place? Food's great, isn't it?"

"She went to school with my mother. I didn't tell her why I was really here," I said. "Nor did I say anything about the shack."

"Well, it won't take long for the truth to get out and around. My daddy says a phone's a waste of money in the bayou. One person tells another something, and it's passed on before the words die on the originator's lips."

"Cajun people are really close, aren't they?"

"One big family," he said proudly. "We have our feuds, though, same as any people."

"I'm half Cajun," I said, "but I feel as if I'm in another country."

"My grandmère used to say you can become Cajun only three ways: by the blood, by the ring, or by the back door. I tell you what," he added, gazing at me, "you got grit like a Cajun. Not many fancy New Orleans girls would come here all alone, I bet, no matter how important it was."

"I don't know what else to do. My mother's not home; my brother's getting worse and worse; Daddy's laid up with a broken leg . . ."

Jack nodded thoughtfully.

Suddenly I realized the storm had stopped. The house was cemetery quiet, and the air was still. "It's over," I said gratefully.

Jack shook his head. "The eye is passing over us. More to come," he predicted, and sure enough, moments later the wind began to whistle through the house again, the shutters slammed and pounded, and the rain splattered and drummed over the trembling windowpanes. Upstairs, a blast of air blew out a pane. We heard it shatter on the floor.

I cringed. Jack held me closer. My heart was pounding so hard I was sure he thought it was his own.

"It'll be all right," he said again. I felt his lips on my hair, his warm breath against my cheek. The terror of the hurricane, the long storm of sadness that had been raining over us, and the desperation of our situation made me long for the calm and the security I found in Jack's arms. He was soft and loving and very sensitive.

I buried my face in his shoulder, unable to keep back the flood of tears. He held me tightly and comforted me as I sobbed. We hadn't known each other long, but his sincerity made that short period seem more like years. The wind howled, the rain stung the house, more things toppled and smashed, another window shattered. It seemed that the world was opening and we would fall into the gaping hole. The sky grew purplish and dark. The kerosene lamp flickered precariously.

"Wow," Jack whispered, and I knew that even he, someone who had been born and lived here all his life, was impressed with this particular storm. The house continued to shake. Everything on hinges was rattling. We clung to each other like two desperate swimmers clinging to a raft in a tossing sea. The wind rose and fell, sending wave after wave of rain against the house.

And then, as suddenly as it had begun, the storm ended. Mother Nature relaxed and stepped over us, the storm trailing after her as she made her way northward to remind someone else how powerful she could be and how much we should all respect her. Jack eased his tight embrace around me, and we both sighed with relief.

"Is it finally over?" I asked, still skeptical.

"Yes," he said. "It's over. I just hate to go out there in daylight tomorrow and see the mess. You all right?"

I nodded, but I didn't leave his side. My heartbeat had slowed, but the numbness I had felt earlier in my legs was still there. I didn't think I could stand up. Jack stroked my hair with his left hand.

"How many of these storms have you been through?" I asked.

"A few, but this was a humdinger."

"I was born during a storm," I told him. "My mother told me about it and how my uncle Paul was there to help with the delivery."

"So that explains it," Jack said.

"Explains what?"

"Where you get your grit . . . from the hurricane. It left its mark in your heart. I bet you're a terror when you're angry."

"No . . . well, maybe," I said.

He laughed. "I don't intend to find out. So," he said sitting back, "what do you plan to do now?" "Nothing. I'm going to wait here," I said.

"You don't really think your mother's coming back, do you?"

"Yes," I said. "She knows I was here; she's got to come back."

Jack thought for a moment. "Okay," he said. "Let's go to my trailer and get some things, see how bad the storm was, and then we'll return."

"No," I said. "I want to stay here. I was going to go through the house just before the storm began. Maybe my mother's hiding someplace."

"You sure got a Cajun stubbornness. When your mind's made up, it's made up," he said. "All right. Wait for me here. We'll search the house again together. I'll go gather up some food for us so we can have dinner."

"I'm not hungry."

"You will be," he assured me. "I'll leave the lantern, but promise you will wait for me before you start trekking through the house again."

"I promise," I said.

He stared at me a moment and then smiled that soft, small smile I was beginning to crave. I smiled back and he leaned toward me as my lips opened slightly to invite his. We kissed.

"I'll be right back," he whispered and put on his slick raincoat and hat. "Don't move."

"Don't worry. I won't," I said.

He laughed and hurried out.

I gazed around the room. In the throes of the storm, I had run to the nearest safe harbor without really looking at my haven. Now, calmer, I looked up at the large oil painting of a cove in the swamps. Although it was too dark to see the details, I had a vision flash across my mind and I saw the grosbeak night heron swooping over the water.

Suddenly a parade of childhood memories began. I saw myself peering down the grand stairway, which to me had looked as deep as the Grand Canyon. I heard laughter in the hallway, the full melodic laugh of my uncle Paul, who beamed his sunny smile at me whenever he saw me. I felt him scoop me up and carry me through the house on his shoulders. Delicious aromas from the kitchen returned. I saw our cook working over the stoves and ordering her assistant to cut this and mix that. All the people in my memories were big, gigantic in word and deed.

As I recalled more and more, the house that was now so dark and dreary was resurrected in my memory. In my recollections it was bright and warm and full of life. Uncle Paul was hanging one of Mommy's new paintings, and I was standing beside her, holding her hand, marveling at the magic that came out of my mother's fingers. With a sweep of a brush, she could put life in a face or make birds fly and fish jump. I heard music and more laughter. There were people everywhere; not a room, not a corner, looked lonely or cold. And from a window, probably in my room, I saw the gardens, bright and lush with flowers in all of the colors of the rainbow.

It seemed to me my mother and I had fled from this house one day, and because the flight was so quick and so complete, my memories had fallen deeper and deeper into the vaults of my mind. It was almost as if I was afraid to let them emerge, afraid that they would return with some horrid nightmare trailing behind them.

The oil wells drummed in the night. Creatures slid along the banks of the swamp, and the water turned inky, dreadful, hiding the face that was to appear on the surface in the yellow moonlight, a face I was yet to see.

I blinked, and the memories faded as quickly as they had come. I was here in the present again, in the dark, dank house, searching for Mommy and hoping to find her before it was too late for all of us.

I didn't move until Jack returned and when he saw that I had barely budged an inch, he laughed. He was carrying a carton filled with food and drink.

"It's too dark to see it all clearly," he said, "but there are trees down, branches scattered, water running every which way. The trailer made out all right, although the phone's dead. I won't be able to inspect the machinery until morning though. I'll set this down on the dining room table," he said, indicating the carton. "Take the lantern and lead the way."

I did so. The sky was still thickly overcast, so the house was very dark. The glow of the lantern cast a dim pool of illumination over the floors and walls, but as we walked through the corridor, darkness seemed to cling to us. Field mice scampered into holes no bigger than quarters. I could hear scratching and scurrying in other rooms, and I surmised that other animals had fled here from the storm.

The dining room table was hidden by a dustcover that had yellowed with time. I pulled it back, and Jack put the carton down. Turning with the lantern, I looked at the walls and ceiling, the grand chandelier and the large windows. Vague images tickled my memory. This table had looked miles long and miles wide to me when I was an infant. The image of Uncle Paul seated at the head flashed in the darkness like a ghost, and I gasped.

"What's wrong?" Jack asked.

I shook my head. "Nothing. I'm fine."

"You want to go through the house again?"

"Please," I replied. He took my hand and the lantern and we checked the kitchen and the pantries and then the sitting rooms before ascending the stairway. Through a window at the end of the upstairs corridor, I saw lightning flash in the distance. I was holding tightly to Jack's hand, squeezing his fingers together, but he didn't appear to mind.

We checked my old nursery, even the closets, checked the guest rooms, Uncle Paul's room and Mommy's. There was no sign of her.

"Where could she be in such a storm?" I mused aloud.

"Maybe she's with someone she didn't talk about much. Maybe she found an old shack and camped out in it, or maybe she went to a motel. There's nothing much you can do tonight, Pearl, with the phones out and the roads closed here and there. Might as well relax as best you can."

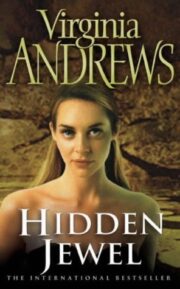

"Hidden Jewel" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Hidden Jewel". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Hidden Jewel" друзьям в соцсетях.