"Pierre moved his finger, Doctor. I felt it. If I can stay with him longer . . ."

"We have to let the nurses do their work and—"

I felt Pierre's fingers move again and cried out. When I turned back to him, his eyelids fluttered.

"Pierre," I said. "Show them. Show them."

His lids fluttered harder and, like eyes that had been closed for centuries, slowly opened.

"Go get Dr. LeFevre," Dr. Lasky ordered the nurse. She hurried away.

I continued to stroke Pierre's hand, cajoling him. "Come on, Pierre. That's it. Try. Come back to us." His eyes remained open.

"That's good," Dr. Lasky muttered behind me. "Hello, Pierre," I said. "Are you feeling better? Do you want to go home soon?"

He turned his head slowly toward me. I saw his lips moving, so I bent down to bring my ear close. He was just putting out enough breath to be heard in a whisper.

"Get Mommy," he said. "Make her come home."

"Oh, yes, Pierre. Yes. I will." I hugged him. "He spoke to me, Doctor!"

"Excellent," Dr. Lasky said and turned to greet Dr. LeFevre, who was rushing toward us. I stepped back as the two of them examined Pierre, and then I decided to go out and get Daddy. I found him in the cafeteria, hovering over a cup of coffee. When I told him the news, his eyes brightened and his face re-gained some color. The two of us hurried back.

Afterward, outside in the corridor, with Daddy and Dr. Lasky at my side, Dr. LeFevre asked me to repeat what I had said and done to get Pierre's reaction. She nodded as she listened.

"You must get your mother home to him soon," she said. "If not, he could relapse again, and I'm afraid each time that happens, he will retreat deeper and deeper inside himself until he becomes irretrievable. Do you understand?"

"Yes," I said and looked at Daddy, who just nodded, a look of terror in his eyes.

"With the diuretic working, we've at least stemmed the threat of acute renal failure for the time being," Dr. Lasky said. "But what happened before can certainly happen again," he cautioned. Neither doctor wanted to leave us with false hope. Their words, although realistic, were as sharp as darts.

Daddy and I returned to Pierre to reassure him we were going to find Mommy and bring her to see him as soon as we could. He listened and then closed his eyes. He was just sleeping now. The great effort to claw his way up and out of the grave his mind was constructing around him had exhausted him. We left him resting comfortably.

"What if Ruby doesn't return, Pearl? What if she never returns?" Daddy asked as we drove home from the hospital.

"She'll come back. She has to."

"Why? She doesn't know what's happening. We can't find her; we can't get a message to her." He shook his head. "If she doesn't come back, poor Pierre . . ."

"We'll sit and we'll think of what else to do, Daddy. We'll find her," I promised, although for the moment I hadn't the slightest idea what we should do next.

The doctors' words lingered like bruised and angry clouds waiting to drop a storm over us. Pierre remained on the brink of oblivion, and we were helpless.

Mommy wasn't there when we returned home, and there had been no phone calls from her or from anyone in the bayou. Daddy phoned Aunt Jeanne and explained the situation. She promised to send out everyone she could and make as many phone calls as she could to people in the area. She said she would contact the police up there for us, too.

"If we don't hear anything tonight or tomorrow morning, we should search for her again, Daddy," I said.

"Search where? We went to the shack and to Cypress Woods. I have no idea where else she might go up there. That part of her life is like a fantasy to me. For all I know there are places and people she never mentioned or that she did mention but I don't remember. You know all of her grandmère's friends are gone. What can we do . . . ride around the back roads, searching the swamps?"

"That would be better than just sitting here, wouldn't it?"

"I don't know, Pearl." He shook his head. "I don't know. What if we go up there, get lost on some back road, and she calls here? No, all we can do is wait."

Neither he nor I had much of an appetite for dinner, but we sat and nibbled. All of the servants were quiet, their faces worried. The house had a funereal atmosphere. No one closed a door hard; everyone tiptoed through the corridors and spoke in whispers. There was no music, no radio or television, just the constant ticking of the grandfather clock followed by its hollow, reverberating gong to announce the passage of time, the flow of minutes without any word from or of Mommy. When Daddy and I gazed at each other, we thought but didn't speak the same thought: back in the hospital, Pierre was waiting, teetering on a tightrope above the dark chasm of gloom that would swallow him and lock him up forever in unconsciousness and finally death. I felt sure that in his mind he saw death as a doorway beyond which Jean stood, waiting.

Neither Daddy nor I knew what we would do or say when we returned to him. He would open his eyes hopefully, expectantly, not see Mommy beside us, and close those eyes again, perhaps forever. We were both terrified of taking the chance, and yet it was hard to keep from visiting him. The longer we stayed away, the deeper his skepticism would become.

Daddy spent some of the evening in his office talking to friends, getting advice. None suggested anything more than what we had already done, and none could understand why Mommy would have run off; but of course few if any of them knew her background and why she had come to believe she was the cause of our trouble.

I wanted to stay awake as late as I could to hear the phone ring, hopefully with news of Mommy, and to keep Daddy company, but when I lowered my head on the sofa and closed my eyes, sleep seized me so quickly I could have been the one in a coma. The next thing I knew, I heard the bong of the grandfather clock declare it was three in the morning.

I sat up slowly, rubbed my eyes, and listened. The house was dead quiet. The lights in the corridors had been turned down low. I was surprised Daddy hadn't come in to wake me and send me up to my bed.

I rubbed the sleep out of my eyes and got up to check on Daddy. The desk lamp in his office was still on, but he wasn't there. I saw that he had done some drinking. The bottle of bourbon was open, and there was a partially filled glass beside it. Thinking he had gone up to bed, I climbed the stairs. My legs felt as if they were filled with water. Every step was an effort. When I got upstairs, I saw that Daddy's bedroom door was open, so I went to it and peeked in.

The bed was empty, the lamp beside it lit. The bathroom door was open, but the bathroom was dark.

"Daddy?" I called quietly. "Are you here?" I listened and heard nothing.

I checked the other bedrooms and didn't find him, so I went back downstairs. The cars were all there, and no one was in the kitchen. I walked through the house and went to Mommy's studio. There were no lights on, so I was going to go back upstairs, frightened now that Daddy might have fallen asleep or collapsed on the floor beside his bed. But as I turned, I caught a whiff of bourbon and paused, staring into the darkness of the studio. My eyes grew used to the absence of light until I saw his silhouette on a settee. I stepped farther into the studio, slowly approaching him.

Daddy was sprawled naked on the settee with just a small towel over his torso. He looked fast asleep. What was he doing? Why had he gotten undressed to lie in here? I debated waking him and then decided to let him rest. Just as I started to turn away again, I heard him cry out my mother's name.

"Ruby. Go on," he muttered. I drew closer again to listen. "Go on," he continued. "You're a professional. You should have no problem drawing me. I want you to do it. Go ahead," he challenged. Then he laughed. "Ready?" He pulled off his towel and cast it over the back of the settee. "Draw with passion, my darling. Draw."

I stood transfixed, unable and afraid to move. I knew if he discovered it was I and not my mother in the darkness, he would be horribly embarrassed. After a moment he lowered his head to the settee again and mumbled something I couldn't hear. He grew quiet, and I tiptoed out of the studio, closing the door softly behind me, leaving Daddy back there, reliving some intimate moment with my mother.

Troubled but exhausted, I put my head on my pillow and fell asleep in moments, glad my mind hadn't the energy to think one more thought.

I awoke with a start. A mourning dove was moaning her ominous, sad cry just under my window. The sky was heavily overcast, shutting out the always welcome rays of warm sunshine and leaving the world draped in a dull film of dreary darkness. Rain was imminent. I gazed at the clock and saw that I had slept until nearly nine. Recalling what had happened the night before, I rose quickly, washed, and dressed. When I descended, I found Daddy, up and dressed and in his office on the telephone. He was speaking to the police in Houma. I stood in the doorway listening.

"Then you have been to the shack and searched the surroundings thoroughly?" he asked, glancing at me cheerlessly. "I see. Yes. We do appreciate that. You have my number, and please, if there is any expense involved . . . I mean, if there's anything extra you can do but can't afford it, . . . of course. Thank you, monsieur. We're grateful."

He cradled the receiver and sat back. His hair was disheveled, his face unshaven and gray, and he was dressed in the wrinkled clothing he had worn yesterday. To me it looked as if he had woken in the studio, dressed, and come to his office.

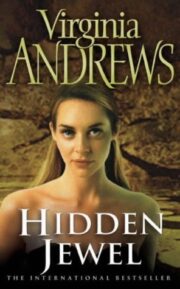

"Hidden Jewel" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Hidden Jewel". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Hidden Jewel" друзьям в соцсетях.