Buck uses the old adage that no publicity is bad publicity, and it’s true that reservations at Raindance nearly quadruple in all three outposts, but that hardly matters to Deacon. Luther Davey calls to tell Deacon he is being put on leave until the brouhaha calms down. Deacon says, “‘Brouhaha’ is a stupid word, Luther. And you don’t have to put me on leave. I put myself on leave. I quit.”

Deacon’s day job isn’t the only thing going down the drain. Belinda is livid with him. She says, “You weren’t thinking about your brand when you made that comment.”

Deacon says, “I don’t have a brand.”

“Okay then,” Belinda says. “You weren’t thinking of my brand.”

This infuriates Deacon. All Belinda cares about is how things reflect upon her.

She says, “There are crack babies dying every hour at St. Vincent’s.”

Deacon laughs derisively. Everything Belinda knows about crack babies she learned from a six-show guest-star appearance on High Street back in the nineties.

“I’ve had it with you,” Deacon says.

“What does that mean?” Belinda says.

“What do you think it means?” Deacon asks. He and Angie are supposed to fly to L.A. the next day for Angie’s spring break, but Deacon doesn’t want to go. He sends Angie out by herself-and there, at the airport, the second after he watches Angie’s plane take off, he starts drinking, and he doesn’t stop until he’s kicking in the back door of Quentin York’s restaurant and humiliating Quentin in front of his line cooks, an escapade that gets him arrested and-because Buck has just left for his honeymoon in Ireland-calling the only friend he has left in the world.

Laurel.

She answers on the first ring. I’ll be right there, she says.

At five in the morning, after Deacon has been released, they go back to his apartment together. He thinks she might try to lecture him or give him a pep talk, but she does neither of these things. She lets him put his head in her lap, and she strokes his hair.

He says, I just want to get away from my life.

So get away, she says. I’ll go with you.

They book flights to the Caribbean. Five nights in an oceanfront suite at Caneel Bay, in St. John. The suite has two bedrooms. They agree that one room will be for Deacon, one for Laurel.

Are you going to tell Belinda you’re going? Laurel asks.

Definitely not. Angie will be gone until a week from Sunday, and the idea of stealing away to a Caribbean paradise with Laurel has taken up residence in his mind. Laurel is going to be the one to save him… again.

He remembers a night their senior year. Laurel is pregnant-she went to prom in a maternity dress and was still the most beautiful girl in the room by far-and she is helping Deacon write his final essay for English. He needs at least a C to pass the class and graduate, and they both know he can’t get a C on his own. The book is Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. They stay up all night drinking Mountain Dew and eating Doritos while Laurel tells Deacon what to write and Deacon writes it. She says, “I’m trying to turn my words into your words.” At four o’clock in the morning, they fall asleep together on the sofa fully dressed, Deacon’s hand resting on Laurel’s pregnant belly.

Deacon gets a C-plus.

Deacon and Laurel walk hand-in-hand through the town of Cruz Bay. They stop for rum drinks, they buy a mango, Deacon picks a hibiscus blossom and tucks it behind Laurel’s ear. She is lightly tanned, she wears no makeup, it doesn’t take her two hours to get ready, she is happy to hike the Reef Bay Trail to see the petroglyphs, which is something Deacon desperately wants to do. He wants to see something that has lasted thousands of years, something that has endured.

They make love. It’s the same; it’s different.

They swim at night under the stars, then climb into bed with sandy feet. When Deacon has a nightmare, Laurel wakes up with him. She scratches his back until he falls back to sleep.

“I love you, Laurel,” he says.

“I know,” she says.

ANGIE

She knocked on the door of Hayes’s room. Scarlett and Ellery had arrived; Angie needed to give her brother fair warning.

There was a muffled groan from within that Angie assumed was an invitation to enter. She opened the door.

“Hayes!” she said. “What happened?” Hayes was lying flat on his back in bed. Half his face was covered in bandages, and the part that wasn’t covered was black-and-blue. The colors were so dark and vivid, they looked like paint. Angie took a few steps closer. Hayes’s lip had been sewn up, and his cheekbone was swollen. “What the fuck happened?”

“Got beat up,” Hayes said, barely moving his lips. There was a tray of juice and toast, untouched, on the chair next to his bed-and on the windowsill, half a glass of water and a prescription bottle. She checked the label: Percocet.

“When?” she said. “And by whom?”

Hayes shrugged. “Last night.”

Angie sat on the bed and studied her brother. He looked exactly like Deacon, but now like a Deacon who had been through the meat grinder.

“Did you call that taxi driver?” she asked. “The guy redefines ‘lunatic fringe.’ Is that who did this?”

“No!” Hayes said. The vehemence in his voice startled Angie. She thought, Definitely the taxi driver. But Hayes seemed keen for her to believe otherwise. Why protect the pirate? Had Hayes made sexual advances? Was Hayes gay? Angie considered this for a moment. Hayes had the ways of a dandy at times-he favored bow ties and bright shirts and fancy shoes. He used to be very particular about how he looked. That had all fallen to the wayside this week, but, of course, their father had died. In the past, Hayes had always had girlfriends, the most excellent of whom was Whitney Jo. Hayes and Whit went out forever, but she eventually left him because he wouldn’t commit. Wouldn’t commit because…? No, Hayes wasn’t gay. He was protecting Pirate for some other reason.

“Were you robbed?” Angie asked.

Hayes nodded.

“What did they take?”

“Everything,” he said.

“So… money, license, credit cards?”

Hayes nodded.

“I can’t believe this,” Angie said. “Have we not been through enough?” She gazed up at the ceiling, where she spied a gray watermark that sort of resembled an octopus. That would be the next thing: the roof would cave in. Hayes looked physically the way Angie felt emotionally. Joel Tersigni had mugged her; he had stolen her heart, her good faith, her confidence.

“Angie,” Hayes said. She could tell he was in pain. “It’s okay. I brought it on myself.”

“Brought it on yourself how?” Angie asked. “Nobody deserves to be robbed and beaten, Hayes.”

Hayes closed his eyes, and Angie felt sorry for yelling. Something was going on with him, but he didn’t want to tell her what it was. Could she blame him? She didn’t exactly feel like explaining how she had started an affair with a married man and had ended up a crash test dummy.

She eyed the prescription bottle. “Do you need a painkiller?”

He held up a hand. “I’m good.”

“You sure?”

He nodded.

“What can I do?” she asked. “Anything to make you feel better?”

He rolled his head so that he was looking at her with his uncovered eye, which was shot through with red veins. He looked like Halloween on a bad acid trip. “You can make Dad’s chowder,” he said.

Angie had to admit: it was a relief to get out of the house, light a cigarette, and climb behind the wheel of Deacon’s old pickup, a 1964 Chevy C10, which smelled like cigarettes and Big Red cinnamon gum.

Angie tried not to think about sitting in the passenger seat of Joel’s Lexus. She tried not to think of his hands resting on the top of the steering wheel, or of the way he played “Colder Weather” every time he took her home. She backed out of the driveway and took off down the road.

She had gone through the drill with Deacon each summer-Sandole’s for seafood and Bartlett’s Farm for produce in the morning, and Sconset Market in the afternoon, their arrival timed for the exact moment when Sally, the baker, was pulling the first batch of baguettes from the oven. Last year, Deacon had discovered a new wine-and-cheese shop on Old South Wharf called Table No. 1, where he’d found both the Pagemaster, which were little buttons of goat-cheese goodness bathed in chocolate whiskey, and Pipe Dreams bouche, the ultimate goat cheese, so they added that stop to the lineup.

Sandole’s would be first, at 167 Hummock Pond Road. Angie hit the gas. She was going to enjoy this, she told herself, even though her heart had split in half like a shell or a nut, one half of it containing grief and the other half rejection. She thought about what JP had told her about his girlfriend-pregnant, then not pregnant, then leaving JP for his best friend, Tommy A. Things changed that way, often without warning. Six weeks earlier, Angie had been working as the fire chief at the restaurant, basically a content and busy person, although with a question mark about Joel’s greater role in her life and a persistent desire to find new ways to impress her father. Now, her life was something she needed to survive.

Angie turned on the truck’s radio. The Clash was singing “Train in Vain.” Angie was so overcome, she had to pull over. What were the chances that the first song she would hear while driving Deacon’s pickup would be that song?

The lines had been tattooed on Deacon’s biceps.

Did you stand by me? No, not at all.

Angie started to cry. Deacon had adored the Clash-this song was his favorite, “Lost in the Supermarket” his runner-up. And because Deacon had loved them, Angie had loved them. That was how it worked, Deacon once told her. First you love the music that your parents love-and then, later in life, you love the songs your kids love.

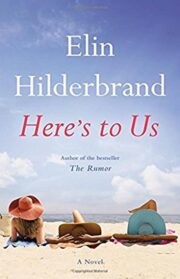

"Here’s to Us" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Here’s to Us". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Here’s to Us" друзьям в соцсетях.