‘Such a sister-in-law, Henry, I should delight in,’ said Eleanor with a smile.

‘But perhaps,’ observed Catherine, being so lacking in self-consequence, vanity and artifice, that she did not know what Eleanor meant, ‘though she has behaved so ill by our family, she may behave better by yours. Now she has really got the man she likes, she may be constant.’

‘Indeed I am afraid she will,’ I replied; ‘I am afraid she will be very constant, unless a baronet should come in her way; that is Frederick’s only chance. I will get the Bath paper, and look over the arrivals.’

‘You think it is all for ambition, then? And, upon my word, there are some things that seem very like it. I cannot forget that, when she first knew what my father would do for them, she seemed quite disappointed that it was not more. I never was so deceived in anyone’s character in my life before.’

‘Among all the great variety that you have known and studied,’ I said, and could not resist a smile.

‘My own disappointment and loss in her is very great; but, as for poor James, I suppose he will hardly ever recover,’ she said sadly.

I felt for her, and thought that the best thing was to laugh her out of her melancholy. For although it was on the surface of it a misfortune, I could not help thinking that James and his sister had both had a very narrow escape.

‘Your brother is certainly very much to be pitied at present; but we must not, in our concern for his sufferings, undervalue yours. You feel, I suppose, that in losing Isabella, you lose half yourself: you feel a void in your heart which nothing else can occupy. Society is becoming irksome; and as for the amusements in which you were wont to share at Bath, the very idea of them without her is abhorrent. You would not, for instance, now go to a ball for the world.’ Becoming a thought more serious, and wanting to show her that what she had lost was not so very great after all, I went on, ‘You feel that you have no longer any friend to whom you can speak with unreserve. No one on whose regard you can place dependence, or whose counsel, in any difficulty, you could rely on. You feel all this?’

‘No,’ she said, after a few moments’ reflection, ‘I do not. Ought I? To say the truth, though I am hurt and grieved, that I cannot still love her, that I am never to hear from her, perhaps never to see her again, I do not feel so very, very much afflicted as one might have supposed.’

Thinking enough time had been spent on such unhappy thoughts, I said, ‘Come, let us explore the woods. It is still spring, whatever our relatives may be doing to upset or vex us, and the day is fine. Who knows, but we may find a hyacinth.’ I turned to Eleanor. ‘Catherine has but lately learned to love a hyacinth.’

‘Then by all means, let us go,’ said Eleanor.

Catherine became calmer throughout the walk, and jumped only twice this evening when Frederick’s name was mentioned by my father, but for the rest of the evening she was tolerably comfortable, and I must hope that by the end of the week she will be able to think of it with no more than a passing sigh.

Wednesday 10 April

The subject of Isabella’s engagement – supposed engagement – to Frederick has been frequently canvassed by Eleanor, Catherine and myself.

‘I cannot believe that Frederick will marry someone as lacking in fortune and consequence as Isabella,’ said Eleanor, as we retired to the library after breakfast, a heavy rain having set in.

‘Even if Frederick was set upon such a path, which I beg leave to doubt, my father will never countenance it,’ I said. ‘He will certainly oppose the connection, and without his blessing it will be difficult for Frederick to marry. He has his soldier’s pay, but that is little enough, and for anything more he still looks to my father.’

‘But I have heard your father say, many times, that he has no interest in money,’ Catherine ventured.

Eleanor and I exchanged glances. It was true that my father frequently said as much, but did not mean it. Why, then, he said it we did not know. To make himself seem more agreeable, perhaps? But why should he want to make himself agreeable to Catherine? It plagued me. As a friend for Eleanor? Yes. But there was something more. As a possible wife for me? But she was no heiress. Was that why he said that money did not count? But why, if money did not count, had he spent so many years throwing heiresses at my head?

‘You must give me warning if your brother is to come to Northanger,’ said Catherine, ‘for indeed, I cannot meet him.’

‘You can be easy on that score, I am sure,’ said Eleanor. ‘Frederick will not have the courage to apply in person for our father’s consent. He has never in his life been less likely to come to Northanger than at the present time.’

Catherine was somewhat mollified, but said, ‘You must tell your father what sort of person Isabella is, for your brother cannot be expected to tell him everything.’

‘He must tell his own story,’ I said.

‘But he will tell only half of it,’ she protested.

‘A quarter would be enough,’ I returned.

‘Perhaps that is why he stays away,’ said Eleanor.

And indeed it seems only too likely.

This mollified Catherine and by and by, when the rain stopped, we walked into the village, where Eleanor wanted to buy some ribbon. The conversation moved on to Catherine’s family and I learned more about her brothers and sisters, all nine of them, and thought what a difference it must make in the family to be ten children instead of three.

‘I have two older brothers besides James,’ said Catherine, ‘and six younger brothers and sisters.’

‘And did you spend your time nursing sick animals when you were younger?’ I asked her.

She looked at me in surprise.

‘No, never. I used to play cricket instead.’

‘You were almost an entire team,’ I said.

‘With Papa, yes, we were, but of course only one team,’ she said. ‘We sometimes played with our neighbours but more usually we made two teams, dividing those who wanted to play into equal numbers, though it was never very equal in other ways because William is always wanting to win and Ned is always thinking about something else – he wants to be an inventor.’

‘And what does he want to invent?’

‘Something to hang the washing out. He is forever thinking of ways to make Mama’s life easier for her, or easier for Papa.’

‘If he ever invents such a marvel you must let me know,’ I said. ‘I am sure I will be able to persuade my father to buy such a machine for the abbey. He has every labour-saving device known and I sometimes think that that is the cause of his bad temper: he has nothing left to improve.’

‘Well, if Ned manages it, I will be sure to tell you,’ she said.

It emerged that she was not particularly fond of music, having learnt the spinet at eight years old and abandoned it at nine; that her sketches were confined to drawings on the backs of envelopes; that she learnt writing and accounts from her father and French from her mother, – ‘but I am not very good at them,’ she artlessly remarked – and that her chief delight as a child had been rolling down the hill at the back of the house.

She drew such a picture of carefree happiness that Eleanor and I were engrossed, for it was a childhood far removed from our own, and although I would like my own children to have a more organized education, I confess I would very much like to see them rolling down the hill at the back of the parsonage, to the scandal – no doubt – of the neighbourhood.

Thursday 11 April

Eleanor and I returned to the subject of Frederick’s absence this morning, whilst Catherine wrote to her brother. We could not decide what Frederick was about.

‘If he truly means to marry Isabella, then he must speak to my father at some point, but he does not show his face,’ I said.

‘I think he stays away because of his engagement,’ said Eleanor. ‘We know he is on leave and there is no need for him to avoid the abbey unless he wishes to avoid our father. He knows how angry Papa will be and he dare not face him.’

‘Frederick has never wanted for courage, whatever else might be his failings: I have been expecting him for days. I cannot understand why he stays away. If he were truly engaged then I think he would come here at once. I think his behaviour is wholly incompatible with the supposed engagement,’ I said. ‘I have wondered at times whether Frederick entered into the engagement for the sole purpose of annoying our father. I have also wondered whether the engagement really exists, except in Isabella’s mind. And even if it exists I wonder whether he will see it through, or will he jilt Isabella, in the way she jilted Morland?’

‘Surely not?’ asked Eleanor, but she did not look convinced. She was thoughtful and then shook her head. ‘It is no good, no matter how much I think about it, it remains a mystery. Frederick does not even write. My father looks for a letter every morning and never finds one.’

‘But Frederick has never been a good correspondent,’ I remarked.

Catherine joining us at that moment, we set out for our walk. Catherine and Eleanor took their sketchpads with them and sat by the lake, as pretty a sight as anyone could wish for, and Eleanor shared her knowledge of art with her willing pupil whilst I entertained them with my conversation. We were enjoying ourselves so much that we lost track of time and were almost late for dinner. Catherine dressed quickly and was downstairs before either Eleanor or myself, a change from the first night when she amused herself by looking through old chests of linen!

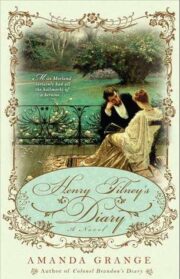

"Henry Tilney’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Henry Tilney’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Henry Tilney’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.