‘No, but I did not expect one,’ she said. ‘James said that he would not reply until his return to Oxford, and Mrs Allen said she would not reply until they had returned to Fullerton. But I am surprised I have not heard from Isabella.’

‘Have you written to her? You know there is paper in the drawing room, with ink and pens and everything you might need? You have only to leave your letters on the table in the hall when you have finished them, and they will be taken to the post with the rest of the mail.’

She thanked me, and said that she had written to Isabella but still not received a reply.

‘It really is unaccountable,’ she said. ‘She promised to write to me and let me know how things went on with James, and when she promises a thing, she is scrupulous in performing it, she told me so herself! I cannot think what has happened unless her letter has gone astray.’

‘I have never known a letter go astray before, but it is certainly possible, and if you have Isabella’s word for her faithfulness as a correspondent you can surely not need anything else,’ I said.

She looked at me doubtfully but I said no more. I leave it to time and experience to teach her the value of the protestations of an Isabella Thorpe.

APRIL

Saturday 6 April

This morning brought a letter from Oxford for Catherine. Knowing how she longed for one, I was happy to hand it to her. She took it eagerly, and sat down to read it. She had not read three lines, however, before her countenance suddenly changed and she let out a cry of sorrowing wonder, showing the letter to contain unpleasant news. Watching her earnestly as she finished, I saw plainly that it had ended no better than it had begun. I was prevented from saying anything by my father’s entrance and we went to breakfast directly, but Catherine could hardly eat anything. Tears filled her eyes, and even ran down her cheeks as she sat. The letter was one moment in her hand, then in her lap, and then in her pocket; and she looked as if she knew not what she did. My father, between his cocoa and his newspaper, had luckily no leisure for noticing her; but to Eleanor and myself her distress was equally visible. As soon as she could, Catherine hurried away to her own room. Eleanor half-rose to follow her, but then thought better of it and sat down again.

‘I will give her a little time to compose herself,’ she said, ‘but then I will go to her.’

We went into the drawing room. Hardly had we begun to speculate on the nature of the news which Catherine had received when, driven from her room by the housemaids, who were making the bed, Catherine opened the door. She hesitated, having evidently sought out the drawing-room for privacy. She drew back, begging our pardon, but such was her distress that I could not bear to leave her to wander the corridors in search of a quiet corner in which to give way to her feelings. I was on my feet at once, and taking her gently by the shoulders I guided her into the room and into a chair.

‘If there is anything I can do to comfort you, then pray let me know,’ said Eleanor tenderly, taking her hand with sympathy. ‘You have had some bad news, I fear.’

But Catherine was too affected to speak.

We withdrew, to give her the privacy she needed, and retired to the breakfast-room, where she joined us half an hour later. After a short silence, Eleanor said, ‘No bad news from Fullerton, I hope? Mr and Mrs Morland – your brothers and sisters – I hope they are none of them ill?’

‘No, I thank you,’ she said with a sigh. ‘They are all very well. My letter was from my brother at Oxford.’ Then speaking through her tears, she added, ‘I do not think I shall ever wish for a letter again!’

‘I am sorry,’ I said, closing the book I had just opened. ‘If I had suspected the letter of containing anything unwelcome, I should have given it with very different feelings.’

‘It contained something worse than anybody could suppose! Poor James is so unhappy!’

I wondered if James was still engaged to Isabella, or if Frederick’s attentions had brought about a breach. If the former, I pitied Morland, and if the latter, I was ashamed of Frederick, but whatever the case, I thought that Morland was lucky to have such a sister. I was tempted to reach out a hand to her but I had to be content with letting Eleanor comfort her instead.

‘To have so kind-hearted, so affectionate a sister,’ I said, ‘must be a comfort to him under any distress.’

She was agitated and did not at once reply, but then she said. ‘I have one favour to beg; that, if your brother should be coming here, you will give me notice of it, that I may go away.’

‘Our brother! Frederick!’ said Eleanor.

‘Yes; I am sure I should be very sorry to leave you so soon, but something has happened that would make it very dreadful for me to be in the same house with Captain Tilney.’

Eleanor was surprised but I realized my suspicions were true and murmured, ‘Miss Thorpe.’

‘How quick you are!’ cried Catherine, ‘you have guessed it, I declare! And yet, when we talked about it in Bath, you little thought of its ending so. Isabella – no wonder now I have not heard from her – Isabella has deserted my brother, and is to marry yours!’

I frowned, for I could not believe it. He was capable of making mischief, but not, I was sure, capable of marrying an Isabella Thorpe.

I said as much, but she replied, ‘It is very true, however; you shall read James’s letter yourself. Stay; there is one part—’

She blushed.

‘Will you take the trouble of reading to us the passages which concern my brother?’ I asked.

‘No, read it yourself,’ cried Catherine, and blushed again. ‘James only means to give me good advice.’

She handed me the letter, and I read it with a mixture of compassion and curiosity, particularly the part she seemed to find embarrassing. Her brother said that all was over between him and Miss Thorpe; that he relied upon his sister’s friendship and love to sustain him; that he hoped her visit to Northanger Abbey would be over before the engagement between Isabella and Frederick was announced, so that she would not be placed in an uncomfortable position; that he had believed that Isabella loved him, because she had said so many times; and that he could not understand why she had led him on, unless it was to attract Frederick the more. But even that reason did not satisfy him, for he could not think it had been necessary, and that he wished now he had never met her, particularly as his father had kindly given his consent to the match.

The last line gave the key to her blushes, for he ended the letter by advising his sister to be careful how she gave her heart.

I was grieved for him, and grieved for Catherine. I was also grieved for Frederick, for whatever his faults, he deserved better than Isabella Thorpe.

I returned the letter, saying, ‘Well, if it is to be so, I can only say that I am sorry for it. Frederick will not be the first man who has chosen a wife with less sense than his family expected. I do not envy his situation, either as a lover or a son.’

Eleanor was looking perplexed, and Catherine handed her the letter.

‘My dear Catherine, I am more sorry than I can say,’ said Eleanor, when she had read it. ‘I can scarcely believe it. I know very little of Isabella, and so I do not know what to think. I saw her once or twice in Bath, but not to speak to, except to exchange the usual pleasantries. I find it hard to believe that Frederick intends to marry her. What are her connections? And what is her fortune? For although I think Frederick would be capable of marrying a woman without either of those things to recommend her, I believe she would have to have a number of personal qualities which Isabella, from my acquaintance with her, would seem to lack. I cannot imagine Frederick risking our father’s displeasure for anything less than love, and I have seen nothing in him lately to suggest that condition.’

‘Her mother is a very good sort of woman,’ was Catherine’s answer.

‘What was her father?’

‘A lawyer, I believe. They live at Putney.’

‘Are they a wealthy family?’

‘No, not very,’ said Catherine. ‘I do not believe Isabella has any fortune at all: but that will not signify in your family. Your father is so very liberal! He told me the other day that he only valued money as it allowed him to promote the happiness of his children.’

Eleanor and I glanced at each other. My father might say that nothing else mattered but unless he had changed even more than we suspected, he was very far from believing it.

‘But,’ said Eleanor, after a short pause, ‘would it be to promote Frederick’s happiness, to enable him to marry such a girl? She must be an unprincipled one, or she could not have used your brother so. And how strange an infatuation on Frederick’s side! A girl who, before his eyes, is violating an engagement voluntarily entered into with another man! Is not it inconceivable, Henry? Frederick too, who always wore his heart so proudly! Who found no woman good enough to be loved!’

‘That is the most unpromising circumstance, the strongest presumption against him. When I think of his past declarations, I give him up. Moreover, I have too good an opinion of Miss Thorpe’s prudence to suppose that she would part with one gentleman before the other was secured. It is all over with Frederick indeed! He is a deceased man – defunct in understanding. Prepare for your sister-in-law, Eleanor, and such a sister-in-law as you must delight in! Open, candid, artless, guileless, with affections strong but simple, forming no pretensions, and knowing no disguise.’

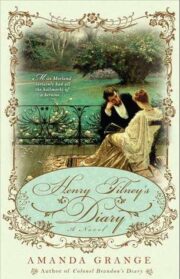

"Henry Tilney’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Henry Tilney’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Henry Tilney’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.