‘As good an argument for the studying of Mrs Radcliffe at Oxford as I have ever heard.’

We walked on, admiring the river and the line of the cliff.

As Eleanor and I discussed its suitability for a sketch, it was easy to see that Miss Morland had not had the benefit of a drawing master and I was happy to instruct her. I soon learnt that she had great natural taste, for when I pointed out the desirability of a drawing having the river in the foreground, with the rolling hills in the distance and a beech tree in the middle distance for perspective, she agreed with everything I said.

Talk of the oak led us to forests, forests to enclosures, enclosures to waste land, and from there it was a short step to politics, which is a subject likely to end any conversation. And so it was with this one.

After a while, Miss Morland recovered from politics and returned to her favourite theme, saying, ‘I have heard that something very shocking indeed will soon come out in London. It is to be uncommonly dreadful. I shall expect murder and everything of the kind.’

Eleanor was alarmed, and Miss Morland was puzzled, and I laughed at them both.

‘You talked of expected horrors in London,’ I said, ‘and instead of instantly conceiving, as any rational creature would have done, that such words could relate only to a circulating library, my sister immediately pictured to herself a mob of three thousand men assembling in St. George’s fields, the Bank attacked, the Tower threatened, the streets of London flowing with blood, a detachment of the Twelfth Light Dragoons (the hopes of the nation) called up from Northampton to quell the insurgents, and the gallant Captain Frederick Tilney, in the moment of charging at the head of his troop, knocked off his horse by a brickbat from an upper window. Forgive her stupidity. The fears of the sister have added to the weakness of the woman; but she is by no means a simpleton in general.’

Eleanor laughed but Miss Morland, unsure whether I were serious or not, looked grave.

‘And now, Henry, that you have made us understand each other, you may as well make Miss Morland understand yourself, unless you mean to have her think you intolerably rude to your sister, and a great brute in your opinion of women in general. Miss Morland is not used to your odd ways,’ Eleanor said.

I smiled at Miss Morland’s expression as understanding dawned, for she was no doubt realizing that Eleanor and I teased each other in the way that she and her brothers and sisters did.

‘I shall be most happy to make her better acquainted with them,’ I said.

My eyes lingered on her face. It really was remarkably pretty, surrounded by soft hair, and I thought that Miss Morland herself would be a fitting subject for a drawing.

‘No doubt; but that is no explanation of the present,’ said Eleanor.

‘What am I to do?’ I asked.

‘You know what you ought to do. Clear your character handsomely before her. Tell her that you think very highly of the understanding of women.’

‘Miss Morland, I think very highly of the understanding of all the women in the world, especially of those – whoever they may be – with whom I happen to be in company.’

‘That is not enough. Be more serious.’

‘Miss Morland, no one can think more highly of the understanding of women than I do. In my opinion, nature has given them so much that they never find it necessary to use more than half.’

Miss Morland looked perplexed, and I thought how well it became her.

‘We shall get nothing more serious from him now, Miss Morland,’ said Eleanor. ‘He is not in a sober mood. But I do assure you that he must be entirely misunderstood, if he can ever appear to say an unjust thing of any woman at all, or an unkind one of me.’

Miss Morland smiled at me. I offered her my arm and as she took it I felt a surprising pleasure at her touch, and we continued with our walk.

Eleanor was not eager to lose Miss Morland’s company, and neither was I. We accompanied her into the house in Pulteney Street where she was residing, and paid our respects to the Allens and then we parted, well pleased with each other.

‘It seems you have found an agreeable friend,’ I said to Eleanor. ‘And, moreover, one my father is disposed to like.’

‘And who would not like her? She is pretty, original, and becomingly ignorant,’ said Eleanor.

I looked at her in surprise.

‘Confess it! You loved instructing her,’ said Eleanor.

‘Instructing her? Nay, we were having an interesting conversation.’

‘Interesting because you did most of the talking!’

‘I happened to know the most about the subject, and besides, I always enjoy talking about art.’

‘Of course, that is the reason and nothing else. Having a pretty young woman hanging on your every word and looking at you with awe has nothing to do with it.’

‘Nothing at all!’

‘Then you are a great deal nobler than the rest of your sex,’ she said with a smile.

‘I have often noticed it.’

‘Be serious!’

‘Well, then, you be serious,’ I replied. ‘I will agree with you that, to the larger and more trifling part of my sex, imbecility in females is a great enhancement of their personal charms; but I will point out that the remaining small portion of them are too reasonable and too well informed themselves to desire anything more in woman than ignorance.’

She laughed.

‘And which kind are you?’ she asked.

‘I am my own kind; I am one of a kind. I require neither imbecility nor ignorance. Let a woman only be pretty, charming, kind to small animals and a lover of novels, and I am content.’

‘Miss Morland manages the first three; only time will tell if she continues to manage the fourth!’

We went into our lodgings and as we went up to the drawing room I said, ‘In all seriousness, I like Miss Morland.’

‘In all seriousness,’ said Eleanor, ‘so do I. And that is fortunate, for with my father’s approval, it seems we are destined to see much more of her.’

Tuesday 5 March

Having some business at the farrier’s, what was my surprise to see Frederick there.

‘I thought you were not coming to Bath until tomorrow,’ I said.

‘That is what I told our father but I arrived yesterday. I was determined to have some time to myself before I enjoyed his paternal affection,’ he replied.

His eyes wandered from me to something over my shoulder and he gave a sneer.

‘Now there goes a happy man,’ he said.

I turned round to see Miss Morland’s brother rushing past.

‘He is on his way to Wiltshire to see his parents and ask for their consent to his marriage. He was in here not ten minutes ago with one of his friends, talking excitedly about it. The fair lady has accepted him, he is beloved by all her family, he is the special friend of her brother – all he needs is the approval of his father and he will willingly slip the noose around his own neck.’

I opened my mouth and then closed it again.

‘What, little brother, no objection to make? That is not like you. You usually remonstrate with me when you hear me slighting the noble institution of matrimony. Have you begun to see the error of your ways?’

‘In general, no,’ I said.

‘But in this case?’

‘Let us just say, I do not envy him his choice of bride.’

‘Ah! So that is it. Well, we will not repine. I dare say he is a fool and not worth our regrets,’ said Frederick with a shrug.

‘He is, from what I know of him, perfectly amiable, and the brother of a friend of mine.’

Something in my voice must have caught his attention, for he said, ‘A friend?’ and looked at me penetratingly.

I had no wish to discuss Miss Morland with him and so I changed the subject, saying, ‘Have you repaid Mr Morris what you owe him yet?’

‘Morris?’ asked Frederick.

‘Yes. Thomas Morris, the man you invited to the abbey because you could not pay him what you owed him last autumn.’

‘Ah, Morris. No, I have not paid him yet,’ he said.

‘Then you must hurry up and do so.’

‘And why must I do so?’ said Frederick provokingly.

‘Because Eleanor is in love with him,’ I replied.

‘Eleanor? In love? I did not know she was in love with anyone, let alone Morris,’ he said in surprise. ‘I never noticed anything of it.’

‘I assure you it is the case, and he is in love with her. So you see you must pay your debt. And no, it is no use your protesting that you cannot afford it, you have your allowance,’ I reminded him.

‘It will not make any difference. Our father will never give him permission, you know that as well as I. The general is eager for Eleanor to make a grand marriage, and if she cannot attract an earl or a viscount, or failing that a man with fifteen thousand a year, then he will marry her off to a relative of one of his cronies. I only wonder that he has not found some friend with a single relative for you.’

‘He has often tried to do so. I am more surprised that he has not found someone for you. He is not happy with you, you know. He expected you to have risen beyond the rank of captain by now.’

‘That is the trouble with having a general for a father, he expects me to reach the same exalted rank, but I have very little interest in soldiering. If I can drink in the mess room and wear a fine coat I am satisfied.’

‘It may satisfy you, but it will not satisfy him, so have a care when you next see him to sound more enthusiastic, or he will stop your allowance.’

‘I wish I did not have to see him at all,’ said Frederick grimly. ‘But enough of the general. I am meeting some friends at a tavern outside town. Come with me.’

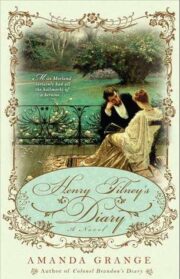

"Henry Tilney’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Henry Tilney’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Henry Tilney’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.