He asked after Frederick and I told him what I knew, that my brother was on the Continent and I did not know when he would return.

He told me of his family, and we discussed politics and business until we could linger no longer, then we went through into the drawing room to join the ladies.

There was a great deal of nonsense talked, as is customary in Bath. There was a little acknowledgement of enjoyment, but a great deal more ennui, and I could not help thinking that some of those present would be less bored were they not so boring themselves. But I did my duty and entertained those who were capable of being entertained and listened to those who were not.

Much was made of the fact that it was St Valentine’s day. Miss Crane and Miss Smith sang songs of maidens languishing for love and knights performing noble deeds, but I suffered their languishing looks in silence, for I was not tempted to slay a dragon, nor even a spider, for either of them.

Friday 15 February

This morning I took a set of rooms for us in Milsom Street and this afternoon went out riding with Charles. This evening we went to the Lower Rooms, which were, for the most part, exceedingly dull. They were full of the usual crowd of people with nothing to say and not a thought between them, but what had been said or thought before. I was introduced to a selection of young ladies by the master of ceremonies, and I obliged them by dancing with them, though there was not one I wished to dance with again, except perhaps Miss Morland. She was new to Bath, having travelled up from the country in company with a Mr and Mrs Allen, and proved to be an entertaining companion. She was not jaded by her surroundings, nor did she pretend to be, and it was entertaining to see how much she enjoyed the bustle, the rooms, the people and the dancing.

Instead of affecting boredom, like the other young ladies, saying that there was not one interesting person to be met with in the whole of Bath, she was charmed, and through her eyes I found that some of the charm of Bath was restored for me. I was amused and pleased with her; so much so, that I invited her to take tea with me. I expected at any moment to be disappointed, as I am usually disappointed, but she did not disgust me by being arch or precocious. She was, if anything, a little too shy, a little too in awe of her surroundings and her company, and I made it my business to tease her into comfort.

After chatting for some time on such matters as naturally arose from the objects around us, I said that I had neglected to ask her how long she had been in Bath; whether she had ever visited before; whether she had been at the Upper Rooms, the theatre, and the concert; and how she liked the place altogether. She said that she liked it very well.

‘Now I must give one smirk, and then we may be rational again,’ I said.

She turned away her head, not knowing whether she might venture to laugh, but a pleasing smile played about her lips. She was not used to being teased – teasing being in short supply in the country, it seems – and I could not resist the urge to tease her further.

‘I see what you think of me,’ I remarked. ‘I shall make but a poor figure in your journal tomorrow.’

‘My journal!’ she exclaimed.

‘Yes, I know exactly what you will say: Friday, went to the Lower Rooms; wore my sprigged muslin robe with blue trimmings – plain black shoes – appeared to much advantage; but was strangely harassed by a queer, half-witted man, who would make me dance with him, and distressed me by his nonsense.’

‘Indeed I shall say no such thing,’ she returned.

‘Shall I tell you what you ought to say?’

‘If you please.’

‘I danced with a very agreeable young man, introduced by Mr King; had a great deal of conversation with him – seems a most extraordinary genius – hope I may know more of him. That, madam, is what I wish you to say.’

‘But, perhaps, I keep no journal,’ she returned, smiling in reply.

‘Perhaps you are not sitting in this room, and I am not sitting by you. Not keep a journal! How are your various dresses to be remembered, and the particular state of your complexion, and curl of your hair to be described in all their diversities, without having constant recourse to a journal? It is this delightful habit of journaling which largely contributes to form the easy style of writing for which ladies are so generally celebrated. Everybody allows that the talent of writing agreeable letters is peculiarly female.’

Still she did not dare to laugh, though I was sure she wanted to.

‘I have sometimes thought,’ she said, ‘whether ladies do write so much better letters than gentlemen! That is, I should not think the superiority was always on our side.’

‘As far as I have had opportunity of judging, it appears to me that the usual style of letter-writing among women is faultless, except in three particulars.’

‘And what are they?’ she asked.

‘A general deficiency of subject, a total inattention to stops, and a very frequent ignorance of grammar.’

I could tease her no more, for we were joined by Mrs Allen, the woman with whom Miss Morland was staying. Indeed, it was Mrs Allen, along with her estimable husband, who had brought Miss Morland to Bath. Journaling and letter-writing were forgotten and muslins became the subject, on account of Mrs Allen’s fearing she had torn hers. She was astonished that I understood muslins.

I told her I understood them particularly well, for I always bought my own cravats, and my sister had often trusted me in the choice of a gown.

‘I bought one for her the other day, and it was pronounced to be a prodigious bargain by every lady who saw it. I gave but five shillings a yard for it, and a true Indian muslin,’ I remarked.

Mrs Allen was quite struck.

‘Men commonly take so little notice of those things,’ said she. ‘I can never get Mr Allen to know one of my gowns from another. You must be a great comfort to your sister, sir.’

‘I hope I am, madam,’ I replied.

‘And pray, sir, what do you think of Miss Morland’s gown?’ she asked me.

I looked at Miss Morland and thought it looked uncommonly charming. I could not say so, however, for fear of producing expectations of an early call, or indeed, an offer of marriage. And so I said, ‘It is very pretty, madam, but I do not think it will wash well; I am afraid it will fray.’

Miss Morland was laughing now, having decided she could, or having realized that she could not help herself, one or the other. ‘How can you,’ she said, ‘be so—’

I had the delightful feeling she was going to say strange, and indeed I was willing her to do so. It would have been amusing to hear such honesty. But she never finished her thought, and Mrs Allen continued to talk of muslins.

I listened politely, though my eyes kept straying to Miss Morland, delighting in her delight at the novelty of her evening. I have been to Bath so many times I had quite forgotten how delightful it can seem to someone who has never been before. So well did I like Miss Morland that when the dancing recommenced I asked for her hand once more.

‘What are you thinking of so earnestly?’ I asked her as we walked back to the ballroom. ‘Not of your partner, I hope, for, by that shake of the head, your meditations are not satis-factory.’

She coloured, and said, ‘I was not thinking of anything.’

‘That is artful and deep, to be sure; but I had rather be told at once that you will not tell me.’

‘Well then, I will not.’

‘Thank you; for now we shall soon be acquainted, as I am authorized to tease you on this subject whenever we meet, and nothing in the world advances intimacy so much.’

She looked delighted at the thought, and was too innocent to disguise it, and my evening was more agreeably spent than I had ever expected.

‘You look very pleased with yourself,’ said Charles, coming up to me.

‘Indeed. I have been thinking that it is company that makes the occasion. The Rooms are often tedious but tonight I found them quite charming.’

‘It is good of you to say so.’

‘My dear Charles, I was not talking of you.’

‘Of course not. Who would be charmed by me when Margaret was by?’

‘I was not thinking of Margaret, either,’ I said. ‘You seemed to dance with her half the evening. It is not done, you know. A man should never pay too much attention to his wife.’

‘I beg you, leave me one of my pleasures. I can no longer scandalize the neighbourhood by stealing apples and so I must make what scandal I can from the means at my disposal.’

‘Very well,’ I conceded. ‘I give you leave to dance with Margaret as much as you like.’

‘You are prodigiously good to me, Henry.’

‘My dear Charles, what are friends for?’

Margaret then joining us, we went out to the carriage.

‘Who was that young lady you were dancing with?’ asked Margaret. ‘I thought her rather pretty.’

‘I danced with any number of pretty ladies,’ I said, as we climbed into the carriage.

‘She is new to Bath. I have not seen her before.’

‘Ah, that young lady. Her name is Miss Morland. She is newly arrived from the country.’

‘You made a handsome couple. When you return to Bath with your family, I hope you will dance with her again,’ Margaret said.

‘When are you returning?’ asked Charles.

‘Charles! Henry has not even left us yet!’

‘No, but I must do so tomorrow, and I hope to return next week,’ I said.

‘Will Mrs Hughes be coming with you?’ asked Margaret.

‘Yes, she comes to keep Eleanor company.’

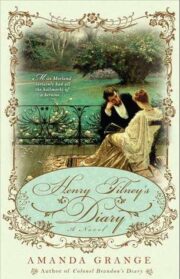

"Henry Tilney’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Henry Tilney’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Henry Tilney’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.