‘As to that, there was some confusion. Mr Morris’s uncle is a viscount, and somehow Frederick had mistaken Mr Morris for the viscount’s son, a very wealthy young man. There is a family resemblance, it seems.’

‘And Mr Morris did not disabuse him of his mistake?’

‘When he discovered it, yes. But by then it was too late. The money was already lent.’

‘And already spent?’ I asked.

‘Unfortunately so, which is why Frederick invited Mr Morris to Northanger Abbey, to make amends.’

‘But whether that will be a good thing or a bad thing remains to be seen. Papa will not countenance a match, you know. He wants you to marry a man of standing, of great wealth and grand position. Someone who will bring renown to the name of Tilney, and, through marriage, add vast estates to our own.’

‘Yes, I know he does, but you go too fast. I have only just met Mr Morris, and although I will confess to having had some conversation with him this morning when you were out with your dogs, I know very little of him and he knows very little of me. There has been no talk of marriage, nor will there be for a very long time, if at all.’

‘But it could happen. Guard yourself, Eleanor. I would not want to see you hurt.’

We sat for some time but, as Mr Morris did not appear, Eleanor at last suggested we continue. She read ever more eagerly as we followed poor Julia’s adventures, and so engrossed were we that we did not notice the arrival of Mr Morris until he cleared his throat.

I looked at him with new eyes. He was handsome enough, with a good bearing and a neat style of dress; nothing ostentatious and yet not shabby; and I wondered how I felt about the idea of his becoming my brother-in-law. His gaze, as it fell on Eleanor, was rapt, and that was a point in his favour, for anyone who marries Eleanor must adore her to have my blessing.

‘Mr Morris. This is a surprise,’ I remarked.

He tore his gaze away from Eleanor, who had flushed, and made his bow.

‘I hope I am not intruding,’ he said.

‘Not at all. We hoped you would join us, did we not, Eleanor?’ I said.

‘We did, indeed.’

He looked surprised and bashfully pleased. This endeared him even more to Eleanor, who invited him to sit down.

‘I see you have brought your book with you.’

‘I rather hoped we might ... that is to say, it was most enjoyable to share the novel ... I do so enjoy reading aloud ... I thought we might do it again.’

‘By all means,’ said Eleanor.

‘I must confess,’ he said, ‘that is to say, I could not sleep and so I succumbed to temptation and read some further passages.’

‘So did we!’ said Eleanor. ‘That is, we have read on this morning.’

‘Ah! Then you know that Julia, helped by her faithful servant, escaped from the marquis and fled to a convent?’ he asked.

‘Yes, we do. And do you know about Hippolitus?’ I asked.

‘That he is alive, having only been severely wounded and not killed? Yes, I know,’ he said. ‘Also, that he sent an emissary to the castle to discover what had happened to Julia, and, finding that she had escaped, he followed her to the convent – only to find that she had fled the convent when the cruel Abate had tried to force her to take the veil.’

‘And do you know about Ferdinand?’ asked Eleanor.

‘That he managed to escape from his father and that he rescued his sister from the convent?’ he asked.

‘Yes,’ said Eleanor. ‘And now Julia and Ferdinand are fleeing through the countryside, pursued by their evil father, with Hippolitus trying to find them.’

‘That is exactly the point I have reached,’ he said.

‘Then let us continue,’ said Eleanor.

As soon as Mr Morris had seated himself beside us she began:

‘Hippolitus gave the reins to his horse, and journeyed on unmindful of his way. The evening was far advanced when he discovered that he had taken a wrong direction, and that he was bewildered in a wild and solitary scene. He had wandered too far from the road to hope to regain it, and he had beside no recollection of the objects left behind him.

‘A choice of errors, only, lay before him. The view on his right hand exhibited high and savage mountains, covered with heath and black fir; and the wild desolation of their aspect, together with the dangerous appearance of the path that wound up their sides, and which was the only apparent track they afforded, determined Hippolitus not to attempt their ascent.

‘On his left lay a forest, to which the path he was then in led; its appearance was gloomy, but he preferred it to the mountains; and, since he was uncertain of its extent, there was a possibility that he might pass it, and reach a village before the night was set in. At the worst, the forest would afford him a shelter from the winds; and, however he might be bewildered in its labyrinths, he could ascend a tree, and rest in security till the return of light should afford him an opportunity of extricating himself.’

A wind blew up and ruffled the pages. Eleanor drew her cloak more tightly about her and smoothed the pages down before continuing:

‘He had not been long in this situation, when a confused sound of voices from a distance roused his attention and he perceived a faint light glimmer through the foliage from afar. The sight revived a hope that he was near some place of human habitation; he therefore unfastened his horse, and led him towards the spot whence the ray issued. The moonlight discovered to him an edifice which appeared to have been formerly a monastery, but which now exhibited a pile of ruins, whose grandeur, heightened by decay, touched the beholder with reverential awe. Seized with unconquerable apprehension, he was retiring, when the low voice of a distressed person struck his ear. He advanced softly and beheld in a small room, which was less decayed than the rest of the edifice, a group of men, who, from the savageness of their looks, and from their dress, appeared to be banditti. They surrounded a man who lay on the ground wounded, and bathed in blood. The obscurity of the place prevented Hippolitus from distinguishing the features of the dying man.’

Eleanor continued to read, but she had to hold the book closer and closer to her face, for dark clouds began to swarm across the sky. She was stopped in mid sentence by an ominous rumble. The sky turned swiftly from blue to black and then the rain began to fall.

As one we sprang up and ran indoors, where we established ourselves in the library just as the storm broke. It was so dark that I lit the candles and we sat around the fire as lightning tore the sky outside. There was a great clap of thunder and Eleanor jumped.

We all laughed, and she said, ‘This is the perfect weather for our occupation. But I have read enough. Mr Morris, will you not read to us instead?’

He took the book hesitantly but the story would brook no delay and he was soon reading in a strong, clear voice.

‘Hippolitus by some mischance attracted the attention of the banditti. He was now returned to a sense of his danger, and endeavoured to escape to the exterior part of the ruin; but terror bewildered his senses, and he mistook his way. Instead of regaining the outside, he perplexed himself with fruitless wanderings, and at length found himself only more deeply involved in the secret recesses of the pile.

‘The steps of his pursuers gained fast upon him. He groped his way along a winding passage, and at length came to a flight of steps. Notwithstanding the darkness, he reached the bottom in safety and there he perceived an object, which fixed all his attention. This was the figure of a young woman lying on the floor apparently dead.

‘Hearing a step advancing towards the room, he concealed himself and presently there came a piercing shriek. The young woman, recovered from her swoon, was now the object of two of the ruffians, who were fighting over their prize.

‘Hippolitus, who was unarmed, insensible to every pulse but that of generous pity, burst into the room, but became fixed like a statue when he beheld his Julia struggling in the grasp of the ruffian. On discovering Hippolitus, she made a sudden spring, and liberated herself; when, running to him, she sunk lifeless in his arms.’

It was at this moment that my father opened the library door and entered with his friends. Mr Morris started. I believe we all, for one moment, expected to see a group of banditti standing there. But even banditti could scarcely have struck us with more dismay, for my father was accompanied by the Marquis of Longtown and General Courteney, with their son and nephew in tow.

‘Ah, there you are,’ said our father to Eleanor. ‘We have been looking for you, have we not, gentlemen? We are all looking forward to hearing you sing for us.’

‘We are indeed,’ they said.

Eleanor threw me a beseeching look but I could do nothing to rescue her, for my father drew her to her feet and gave her up to the Marquis’s son on one side, and the general’s nephew on the other. I followed them to the drawing room, where Frederick looked on with a disdainful eye and Miss Barton amused herself by flirting.

Eleanor went over to the piano and I stood by her, ready to turn her music. Poor Morris took a seat in the corner, a picture of dejection.

I believe we would all three of us have preferred to remain by the fire, whilst the thunder rolled and the lightning cracked, reading to each other.

Sunday 11 November

‘And what do you think of Miss Barton?’ asked my father this morning, when he met me at breakfast.

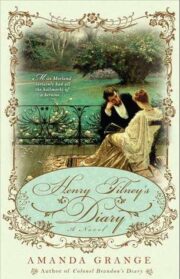

"Henry Tilney’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Henry Tilney’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Henry Tilney’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.