"Although I don't honestly know what I could have done," Father Dom said, rifling through Paul's file, "to prevent his being admitted. His test scores, grades, teacher evaluations . . . everything is exemplary. I am sorry to say that on paper, Paul Slater comes off as a far better student than you did when you first applied to this school."

"You can't tell anything," I pointed out, "about a person's moral fiber from a bunch of test scores." I am a little defensive about this topic, on account of my own test scores having been mediocre enough to have caused the Mission Academy to balk at accepting my application eight months ago when my mother announced we were moving to California so that she could marry Andy Ackerman, the man of her dreams, and now my stepfather.

"No," Father Dominic said, tiredly removing his glasses and cleaning them on the hem of his long black robe. There were, I noticed, purple shadows beneath his eyes. "No, you cannot," he agreed with a deep sigh, placing his wire rims back over the bridge of his perfectly aquiline nose. "Susannah, are you really so certain this boy's motives are less than noble? Perhaps Paul is looking for guidance. It's possible, that with the right influence, he might be made to see the error of his ways. . . ."

"Yeah, Father Dom," I said sarcastically. "And maybe this year I'll get elected Homecoming Queen."

Father Dominic looked disapproving. Unlike me, Father Dominic tended always to think the best of people, at least until their subsequent behavior proved his assumption in their inherent goodness to be wrong. You would think that in the case of Paul Slater, he'd have already seen enough to form a solid basis for judgment on that guy's behalf, but apparently not.

"I am going to assume," Father D. said, "until we've seen something to prove otherwise, that Paul is here at the Mission Academy because he wants to learn. Not just the normal eleventh grade curriculum, either, Susannah, but what you and I might have to teach him as well. Let us hope that Paul regrets his past actions and truly wishes to make amends. I believe that Paul is here to make a fresh start rather like you did last year, if you'll recall. And it is our duty, as charitable human beings, to help him do just that. Until we learn otherwise, I believe we should give Paul the benefit of the doubt."

I thought this was the worst plan I had ever heard in my life. But the truth was, I didn't have any evidence that Paul was, in fact, here to cause trouble. Not yet, anyway.

"Now," Father D. said, closing Paul's file and leaning back in his chair, "I haven't seen you in a few weeks. How are you, Susannah? And how's Jesse?"

I felt my face heat up. Things were at a sorry pass when the mere mention of Jesse's name could cause me to blush, but there it was.

"Um," I said, hoping Father D. wouldn't notice my flaming cheeks. "Fine."

"Good," Father Dom said, pushing his glasses up on his nose and looking over at his bookshelf in a distracted manner. "There was a book he mentioned he wanted to borrow - Oh, yes, here it is." Father Dom placed a giant, leatherbound book - it had to have weighed ten pounds at least - in my arms. "Critical Theory Since Plato," he said with a smile. "Jesse ought to like that."

I didn't doubt it. Jesse liked some of the most boring books known to man. Possibly this was why he wasn't responding to me. I mean, not the way I wanted him to. Because I was not boring enough.

"Very good," Father D. said distractedly. You could tell he had a lot on his mind. Visits from the archbishop always threw him into a tizzy, and this one, for the feast of Father Serra, whom several organizations had been trying unsuccessfully to have made a saint, was going to be a particularly huge pain in the butt, from what I could see.

"Let's just keep an eye on our young friend Mr. Slater," Father Dom went on, "and see how things go. He might very well settle down, Susannah, in a structured environment like the one we offer here at the academy."

I sniffed. I couldn't help it. Father D. really had no idea what he was up against.

"And if he doesn't?" I asked.

"Well," Father Dominic said. "We'll cross that bridge when we get to it. Now run along. You don't want to waste the whole of your lunch break in here with me."

Reluctantly, I left the principal's office, carrying the dusty old tome he'd given me. The morning fog had dispersed, as it always did around eleven, and now the sky overhead was a brilliant blue. In the courtyard, hummingbirds busily worked over the hibiscus. The fountain, surrounded by a half-dozen tourists in Bermuda shorts - the mission, besides being a school, was also a historic landmark and sported a basilica and even a gift shop that were must-sees on any touring bus's schedule - burbled noisily. The deep green fronds of the palm trees waved lazily overhead in the gentle breeze from the sea. It was another gorgeous day in Carmel-by-the-Sea.

So why did I feel so wretched?

I tried to tell myself that I was overreacting. That Father Dom was right - we didn't know what Paul's motives in coming to Carmel were. Perhaps he really had turned over a new leaf.

So why could I not get that image - the one from my nightmares - out of my head? The long dark hallway and me running through it, looking desperately for a way out, and finding only fog. It was a dream I had nearly once a night, and from which I never failed to wake in a sweat.

Truthfully, I didn't know which was scarier: my nightmare or what was happening now while I was awake. What was Paul doing here? Even more perplexing, how was it that Paul seemed to know so much about the talent he and I shared? There's no newsletter. There are no conferences or seminars. When you put the word mediator into any search engine online, all you get is stuff about lawyers and family counsellors. I am as clueless now, practically, as I'd been back when I was little and known only that I was . . . well, different from the other kids in my neighborhood.

But Paul. Paul seemed to think he had some kinds of answers.

What could he know about it, though? Even Father Dominic didn't claim to know exactly what we mediators - for lack of a better term - were, and where we'd come from, and just what, exactly, were the extent of our talents . . . and he was older than both of us combined! Sure, we can see and speak to - and even kiss and punch - the dead ... or rather, with the spirits of those who had died leaving things untidy, something I'd found out at the age of six, when my dad, who'd passed away from a sudden heart attack, came back for a little post-funeral chat.

But was that it? I mean, was that all mediators were capable of? Not according to Paul.

Despite Father Dominic's assurances that Paul likely meant well, I could not be so sure. People like Paul did not do anything without good reason. So what was he doing back in Carmel? Could it be merely that, now that he'd discovered Father Dom and me, he wished to continue the relationship out of some kind of longing to be with his own kind?

It was possible. Of course, it's equally possible that Jesse really does love me and is just pretending he doesn't, since a romantic relationship between the two of us really wouldn't be all that kosher. . . .

Yeah. And maybe I really will get that Homecoming Queen nomination I've been longing for. . . .

I was still trying not to think about this at lunch - the Paul thing, not the Homecoming Queen thing - when, sandwiched on an outdoor bench between Adam and CeeCee, I cracked the pull tab on a can of diet soda and then nearly choked on my first swallow after CeeCee went, "So, spill. Who's this Jesse guy anyway? Answer please this time."

Soda went everywhere, mostly out of my nose. Some of it got on my Benetton sweater set.

CeeCee was completely unsympathetic. "It's diet," she said. "It won't stain. So how come we haven't met him?"

"Yeah," Adam said, getting over his initial mirth at seeing soda coming out of my nostrils. "And how come this Paul guy knows him, and we don't?"

Dabbing myself with a napkin, I glanced in Paul's direction. He was sitting on a bench not too far away, surrounded by Kelly Prescott and the other popular people in our class, all of whom were laughing uproariously at some story he'd just told them.

"Jesse's just a guy," I said, because I had a feeling I wasn't going to be able to get away with brushing their questions off. Not this time.

"Just a guy," CeeCee repeated. "Just a guy you are apparently going out with, according to this Paul."

"Well," I said uncomfortably. "Yeah. I guess I am. Sort of. I mean . . . it's complicated."

Complicated? My relationship with Jesse made Critical Theory Since Plato look like The Poky Little Puppy.

"So," CeeCee said, crossing her legs and nibbling contentedly from a bag of baby carrots in her lap. "Tell. Where'd you two meet?"

I could not believe I was actually sitting there, discussing Jesse with my friends. My friends whom I'd worked so hard to keep in the dark about him.

"He, um, lives in my neighborhood," I said. No point in telling them the absolute truth.

"He go to RLS?" Adam wanted to know, referring to Robert Louis Stevenson High and reaching over me to grab a carrot from the bag in CeeCee's lap.

"Um," I said. "Not exactly."

"Don't tell me he goes to Carmel High." CeeCee's eyes widened.

"He's not in high school anymore," I said, since I knew that, given CeeCee's nature, she'd never rest until she knew all. "He, um, graduated already."

"Whoa," CeeCee said. "An older man. Well, no wonder you're keeping him a secret. So, what is he, in college?"

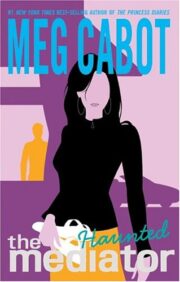

"Haunted" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Haunted". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Haunted" друзьям в соцсетях.