"Would you get off it, Suze?" he said, rolling his eyes. "Your virtue's in no danger from me. I swear 111 keep my hands to myself. This is business.

There'll be plenty of time for fun later."

I tried to smile coolly, so he wouldn't suspect that I am not accustomed to people - okay, guys - saying this sort of thing to me every day. But the truth is, of course I'm not. And it bugged me the way it made me feel when Paul did it. I mean, I did not even like this guy, but every time he said something like that - suggested that he thought I was, I don't know, special - it sent this little shiver down my spine . . . and not in a bad way.

That was the thing. It wasn't in a bad way. What was that all about? I mean, I don't even like Paul. I am fully in love with somebody else. And, yeah, Jesse is presently showing no signs of actually returning my feelings, but it's not like because of that I am suddenly going to start going out with Paul Slater ... no matter how good he might look in his Ray-Bans.

I got out of the car.

"Wise decision," Paul commented, closing the car door behind me.

There was a sort of finality in the sound of that door being slammed shut. I tried not to think about what I might be letting myself in for as I followed Paul up the cement steps to the wide glass front door to his grandfather's house, barefoot, my Jimmy Choos in one hand and my book bag in the other.

Inside the Slaters' house, it was cool and quiet ... so quiet, you couldn't even hear the pounding surf of the ocean not a hundred feet below it. Whoever had decorated the place had taste that ran toward the modern, so everything looked sleek and new and uncomfortable. The house, I imagined, must have been freezing in the morning when the fog rolled in, since everything in it was made of glass or metal. Paul led me up a twisting steel staircase from the front door to the high-tech kitchen, where all the appliances gleamed aggressively.

"Cocktail?" he asked me, opening a glass door to a liquor cabinet.

"Very funny," I said. "Just water, please. Where's your grandfather?"

"Down the hall," Paul said, as he pulled two bottles of designer water from the enormous Sub-Zero fridge. He must have noticed my nervous glance over my shoulder, since he added, "Go take a look for yourself if you don't believe me."

I went to take a look for myself. It wasn't that I didn't trust him . . . well, okay, it was. Though it would have been pretty bold of him to lie about something I could so easily check. And what was I going to do if it turned out his grandfather wasn't there? I mean, no way was I leaving before I'd found out what I'd come to learn.

Fortunately, it appeared I wouldn't have to. Hearing some faint sounds, I followed them down a long glass hallway, until I came to a room in which a wide-screen television was on. In front of the television sat a very old man in a very high-tech wheelchair. Beside the wheelchair, in a very uncomfortable-looking modern chair, sat a youngish guy in a blue nurse's uniform, reading a magazine. He looked up when I appeared in the doorway and smiled.

"Hey," he said.

"Hey," I said back, and came tentatively into the room. It was a nice room, with one of the better views in the house, I imagined. It had been furnished with a hospital bed, complete with an IV bag and adjustable frame and metal bookshelves on which rested frame after frame of photographs. Black-and-white photographs mostly, judging by their outfits, of people from the forties.

"Um," I said to the old man in the wheelchair. "Hi, Mr. Slater. I'm Susannah Simon."

The old man didn't say anything. He didn't even take his gaze from the game show that was on in front of him. He was mostly bald and pretty much covered in liver spots, and he was drooling a little. The nurse noticed 'this and leaned over with a handkerchief to wipe the old man's mouth.

"There you go, Mr. Slater," the nurse said. "The nice young lady said hello. Aren't you going to say hello back?"

But Mr. Slater didn't say anything. Instead, Paul, who'd come into the room behind me, went, "How's it going, Pops? Had another riveting day in front of the old boob tube?"

Mr. Slater did not acknowledge Paul, either. The nurse said, "We had a good day, didn't we, Mr. Slater? Took a nice walk in the backyard around the pool and picked a few lemons."

"That's great," Paul said with forced enthusiasm. Then he took my hand and started to drag me from the room. I will admit he didn't have to drag hard. I was pretty creeped out, and went willingly enough. Which is saying a lot, considering how I felt about Paul and everything. I mean, that there was someone who creeped me out more than he did.

"Bye, Mr. Slater," I said, not expecting a response . . . which was a good thing, since I got none.

Out in the hallway, I asked quietly, "What's wrong with him? Alzheimer's?"

"Naw," Paul said, handing me one of the dark-blue bottles of water. "They don't know, exactly. He's lucid enough, when he wants to be."

"Really?" I had a hard time believing it. Lucid people can usually maintain some control over their own saliva. "Maybe he's just. . . you know. Old."

"Yeah," Paul said with another of his trademark bitter laughs. "That's probably it, all right." Then, without elaborating further, he threw open a door on his right and said, "This is it. What I wanted to show you."

I followed him into what was, clearly, his bedroom. It was about five times as big as my own room - and Paul's bed was about five times bigger than mine. Like the rest of the house, everything was very streamlined and modern, with a lot of metal and glass. There was even a glass desk - or Plexiglas, probably - on which rested a brand-new, top-of-the-line laptop. There was none of the kind of personal stuff lying around Paul's room that always seemed to be scattered around mine - like magazines or dirty socks or nail polish or half-eaten boxes of Girl Scout cookies. There was nothing personal in Paul's room at all. It was like a very high-tech, very cold hotel room.

"It's here," Paul said, sitting down on the edge of his boat-sized bed.

"Yeah," I said, more spooked than ever now ... and not just because Paul was patting the empty space on the mattress beside him. No, it was also the fact that the only color in the room, besides what Paul and I were wearing, was what I could see out the enormous plate glass windows: the blue, blue sky and below it, the darker blue sea. "Sure it is."

"I'm serious," Paul said, and he quit patting the mattress like he wanted me to sit beside him. Instead, he reached beneath the bed and pulled out a clear plastic box, like the kind you store wool sweaters in over the summer.

Placing the box beside him on the bed, Paul pulled off the lid. Inside were what looked to be a number of newspaper and magazine articles, each one carefully clipped from its original source.

"Check these out," Paul said, carefully unfolding a particularly ancient newspaper article and spreading it out across the slate-gray bedspread so that I could see it. It came from the London Times, and was dated June 18, 1952. There was a photograph of a man standing before what looked like the hieroglyphic-covered wall of an Egyptian tomb. The headline above the photo and article ran, "Archaeologist's Theory Scoffed at by Skeptics."

"Dr. Oliver Slaski - that's this guy here in the photo - worked for years to translate the text on the wall of King Tut's tomb," Paul explained. "He came to the conclusion that in ancient Egypt there was actually a small group of shamans who had the ability to travel in and out of the realm of the dead without, in fact, dying themselves. These shamans were called, as near as Dr. Slaski could translate, shifters. They could shift from this plane of being to the next, and were hired as spirit guides for the deceased by the deceased's family, in order to ensure their loved one's ending up where he was supposed to instead of aimlessly wandering the planet."

I had sunk down onto the bed as Paul had been speaking so that I could get a better look at the picture he was indicating. I had been hesitant to do so before - I didn't really want to get near Paul at all, especially considering the whole bed thing.

Now, however, I hardly noticed how close we were sitting together. I leaned forward to stare at the picture until my hair brushed against the cracked and yellowed paper.

"Shifters," I said, through lips that had gone strangely cold, as if I had put Carmex on them. Only I hadn't. "What he meant was mediators."

"I don't think so," Paul said.

"No," I said. I was feeling sort of breathless. Well, you would, too, if your whole life you had wondered why you were so different from everyone you knew and then all of a sudden, one day you found out. Or at least got hold of a very important clue.

"That is exactly what it means, Paul," I exclaimed. "The ninth card in the tarot deck - the one called the Hermit - features an old man holding a lantern, just like this guy is doing," I said, indicating the guy in the hieroglyphic. "It always comes up when my cards are read. And the Hermit is a spirit guide, someone who is supposed to lead the dead to their final destination. And okay, the guy in the hieroglyphic isn't old, but they are both doing the same thing. . . . He has to mean mediators, Paul," I said, my heart thudding hard against my ribs. This was big. Really big. The fact that there was actual documented proof of the existence of people like me ... I had never hoped to see such a thing. I couldn't wait to tell Father Dominic. "He has to!"

"But that's not all they were, Suze," Paul said, reaching back into the acrylic box and bringing out a sheaf of papers, also brown with age. "According to Slaski, who wrote this thesis about it, back in ancient Egypt there were your run-of-the-mill mediums, or, if you prefer, mediators. But then there were also shifters. And that," Paul said, looking at me very intently from across the bed, and not very far across the bed, either, as we were leaning only about a foot apart, the pages of Dr. Slaski's thesis between us, "is what you and I are, Suze. Shifters."

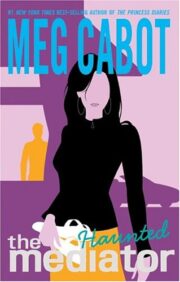

"Haunted" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Haunted". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Haunted" друзьям в соцсетях.