Lowe grunted.

“Goddammit, Lowe.”

“It wasn’t Adam’s fault—his reproduction was spotless. It was the fucking paperwork. Monk didn’t even notice the error. It was the person he sold it to.”

Winter’s eyes briefly closed. “Which is who?”

“No idea. It was a silent sale.”

“So what does Monk want from you now?”

“I think he wants his money back, but he might want my head, as well.”

“Why don’t you compromise and give him the real statue.”

Impossible to give what he didn’t have. The whole purpose of the forgery was to generate two sales. Lowe gave a polite nod to one of the nosier nuns as she passed. Yes, Sister, he thought, you aren’t wrong to suspect the Magnusson boys of vice and lies. We are the reason people need to purge themselves in your confessional booths. Nothing to see. Move along.

Winter flexed his hand like he might be thinking about taking Monk’s side. “How much do you owe him?”

“I’ve got a plan, don’t worry.”

“One that doesn’t involve begging me for money?”

“Never begged you before. Don’t plan to start now.”

“Good, because my liquid assets this month are tied up in a new warehouse in Marin County, and I recently paid out Christmas bonuses to my people and—”

“Ja, ja! I said I wasn’t asking.” Not that he hadn’t considered it, but still.

The last nun passed by. Winter gripped the back of Lowe’s neck and whispered hotly into his ear, “Fix it with Morales. I’ve got a baby on the way. Don’t bring that shit to our doorstep.”

• • •

After leaving Lowe, Hadley spent several minutes calming her erratic feelings. Why she’d gotten so upset in front his family, she didn’t really know. But once they were gone, she put Lowe out of her mind and waited nearly two hours in the Twin Peaks lobby, hoping her lost luggage was on the 127. It wasn’t. So she filed a claim with the manager, listening to his secondhand account of the events at the Salt Lake City station. No one knew why the incident had happened and the police weren’t able to apprehend the gunmen. Maybe they’d follow Lowe here to finish the job.

It was dark when the taxi took her through the Castro and the Mission District, and finally down the steep bend of California Street to her Nob Hill apartment building at Mason. The elegant nine-story high-rise was only a year old and very exclusive. Only the best, her father had encouraged when she’d decided to move out of the family home.

Tendrils of nighttime fog clung to French columns flanking the driveway. She paid the taxi driver and breezed through the small lobby, waving at an attendant who barely lifted his head—did he even know her name?—before stepping onto the elevator.

“Miss Bacall.” Finally, a friendly face. The graying elevator operator greeted her with his usual broad smile. “How was your trip?”

“Hectic, Mr. Walter. Very hectic. I’m relieved to be home.”

“No luggage?”

She wilted against the elevator wall. “No luggage. It’s a long story, I’m afraid. Hopefully it will be delivered tomorrow.”

He shut the scissor gate and engaged the elevator. “You’re deliberately trying to intrigue me, I think. But I won’t press. How about your class at the university? Did they like what you had to say about Egyptian cats?”

“They were attentive.” The ones who didn’t leave or fall asleep. She knew she wasn’t the liveliest public speaker. One of her coworkers, George, said listening to her speak was akin to enduring an accountant’s eulogy. She knew he wasn’t wrong; giving seminars made her uncomfortable. But if she wanted to rise above her curation pay—and George—it was a necessary evil, and one that she’d gladly submit to. She wanted her father’s position as department head more than just about anything.

But answering rote questions in front of bored college students at a podunk university was a one-way conversation. Not like the spirited discussion she’d had on the train that afternoon with Lowe. To her great surprise, he wasn’t just a dumb treasure hunter who’d stumbled upon the djed. He knew things. He could read hieroglyphics, and he’d even learned some of the Nubi language from the local Aswan workers on his excavation. He told her stories about the historic book market in Alexandria, and asked for details about her seminar.

He listened. He asked questions.

He argued.

He might not agree with all her funerary tool theories, and he wasn’t precise with dynasty dates, but he certainly wasn’t stupid. And he had an easy, unpretentious way of talking that she didn’t encounter much in her line of work.

He also lied about anything and everything under the sun. And beyond the seeming lightheartedness of it, she realized now that he was a master of deflection. All their chatting, all that time spent together, and he’d barely revealed a single personal detail about himself.

Floor numbers scrolled past the scissor gates as they ascended. Mr. Walter chatted about the winter rain they’d been getting and how it hadn’t slowed a drunken hellfire party going on at the Pacific Union Club, the men’s club across the street. On the ninth floor, he bid her good night.

In the entry to her apartment, she stepped on an envelope when she shrugged out of her coat. She weighted it in her hand. Not good, she feared.

“Mrs. Durer?” she called out.

Her maid did not answer.

A fitting end to her dreary day.

The click of her heels on polished marble bounced around the high walls of her spacious living room. The windows here looked out over the twinkling lights of the Fairmont Hotel—a beautiful building, always busy with people coming and going. And the steady rumble of cars and occasional clack of the cable cars braving the steep hill kept her company, night or day.

Like the rest of her apartment, the master bedroom contained a minimal amount of furniture. Everything was bolted down: bed, nightstand, chaise lounge. In the six months she’d lived there, her specters had blown out two windows and three light fixtures and had overturned a large armoire. Best not to give them any extra kindling, she found.

Her father called them Mori. Death specters. Her mother became cursed with them after a trip to Egypt, and when she died, they were passed on to Hadley. Strong, negative emotions called them up, fueled them. Shadowy tricksters, her father had explained when she was a child.

“Trickster” seemed too kind a word for spirits with the power to kill.

The only companion sturdy enough to survive her angry moods was a sleek black cat. Lounging on her silk coverlet, he stretched his long limbs in greeting when she dropped her handbag on the nightstand.

“Hello, Number Four,” she said, running a hand along his soft belly. He answered with an enthusiastic purr.

Because of her unusual curse, she’d never been allowed to have pets as a child. A necessary precaution, even now. God knew she wouldn’t normally even consider subjecting an innocent life to her murderous moods. But she didn’t seek out Number Four—she’d found him hiding in the pantry after she moved in. And though she’d tried to shoo him away, he just kept coming back, again and again, so she finally allowed the stubborn creature to stay.

A few months ago, he was Number Three, until he was caught in the cross fire of a fight between her and her father: the cat had hidden under a chair the specters reduced to matchsticks. But just as he’d done the first two times he’d gotten on the wrong side of the specters, the cat managed to pick himself back up and simply kept on ticking.

Nine lives, as the superstition goes. Seeing how he was on this fourth already, by her count, Hadley figured he had five more left. He was an odd sort of miracle, that cat of hers.

A lot like her, really.

She tried not to think about Lowe when she stripped off her clothes and tossed the ripped dress in a wastebasket. Unbelievable that she’d spent last night and most of today with him. The whole thing felt surreal to her now, like a dream. Or a gaudy nightmare.

Stretching out on the bed with Number Four, she held up the found envelope to her reading lamp above the headboard. The silhouette of a key and a letter appeared against the golden light. She ripped off the side of the envelope and tipped it into her open palm. Her apartment key fell out. The metal was cold against her fist as she skimmed the handwritten letter from her latest maid: Miss Bacall . . . Grateful for my time in your service . . . however, I must take my leave . . . My nerves are frayed . . . Feel as if the devil dwells inside you . . . bad luck . . . Will pray for you and that demonic cat.

“Another servant bites the dust,” she said to Number Four. “Good riddance, you say? Why, Number Four, that’s not very nice. Then again, neither was Mrs. Durer, and she did call you demonic. We’ll contact the agency tomorrow and find someone less evangelical.”

He purred in agreement.

She wasn’t sad to see the woman go, exactly. But as she stared out the window past the city lights, she couldn’t help but think of Lowe and his boisterous family. From the train’s window, she’d watched the warm greeting they gave him, all hugs and smiles and laughter.

No one had bothered to welcome her home. Her father probably hadn’t even remembered she’d left town. A shame that the only person who knew her comings and goings was the elevator operator.

No, she wasn’t sad that another maid had quit. But she was sad that the old woman’s quick departure left Hadley alone in the middle of a busy city. And she was sad that it made her feel so needy. Not for the first time, she wished that she could come home and count on someone being there. A warm body. Another voice.

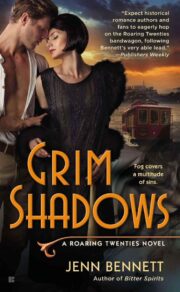

"Grim Shadows" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Grim Shadows". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Grim Shadows" друзьям в соцсетях.