“Did you see that?” he said, holding his arms out as if he’d lost his balance.

“I saw it.”

“Is the train rocking? What just happened?”

“It’s over,” she said, trying her best to play dumb. “So, what’s your plan now, Mr. Magnusson? Do we hole up in here for the next, what, eighteen hours, until we make it to San Francisco? Or do we jump off at the next stop?”

“Christ. I don’t know.” He straightened the satchel strapped to his chest and cast one more bewildered look at the fallen luggage at his feet. “What’s your thought on the matter?”

Oh, now he was asking her opinion?

She considered their situation. “No decent-sized stations until Reno, so chances of finding an open ticket office at this time of night are slim to none.”

“Probably right about that. We’d have to sleep in the lobby and wait for the next train, maybe until this time tomorrow.” He blew out a long breath. “And I haven’t been home in nine months. Also haven’t had a decent night’s sleep in several weeks, so waiting’s not my preference. What’s in the next car? Can you peer through the window shade?”

She started for the inner door, but remembered what’d happened on the train’s platform and hurriedly slipped into her coat.

“Too late. I’ve already seen everything.” He turned sideways as he slipped past her. “Highlight of my entire trip home,” he murmured with a merry lilt.

An unwanted thrill chased away any modicum of shame she might’ve felt. For the love of God, what was the matter with her, falling for empty flattery? And why was it so warm in here? She discreetly fanned her face while he peeked into the next car.

“Kitchen car. Looks to be empty.” He motioned for her without looking. “If we get caught, leave the talking to me.”

They hurried through. Fresh-brewed coffee and toasted bread made her stomach groan. The next car was a cigarette-smoke-filled observation room—only one passenger here, and he didn’t even look up from his newspaper when they passed. The next car was a sleeper. A few private compartments lined the left side of a narrow passageway that spilled into the open public area.

“‘Manager’s Office,’” Mr. Magnusson read from gold-stenciled wood. They walked farther. “Ah, here are the compartments.” Occupied, occupied, occupied. The last compartment door slid open, and out stepped a gangly young man in a railway uniform. He couldn’t have been older than seventeen or eighteen.

“Pardon me, sir,” he said, dropping his eyes as he stepped back into the stateroom to allow them room to pass.

“This one’s not occupied?” Mr. Magnusson asked.

“Not at the moment, sir.”

Mr. Magnusson flashed the porter a train ticket. “We were on the 127, my sister and I,” he said, motioning to include her. “They switched us to this train in Salt Lake City. My sister’s husband . . . well, there’s no sense in mincing words. The man’s a mean drunk, and he was threatening her, you see. And she’s got a bun in the oven. A bad situation.”

Hadley’s mouth fell open.

The porter looked as confused as she felt. “Yes, sir.”

“So they were kind enough to move us,” Magnusson continued. “They told us to come aboard, and that the ticket office manager would bring us the new tickets while they called the police—you know, to detain her husband. For her protection.”

“Oh, my,” the porter said, leaning to get a better look at her.

“Only, the train left the station, and the manager never came. So now our luggage is on the 127, and we’re stuck here without a stateroom assignment.”

“No one informed me,” the porter said.

“It happened so fast,” Magnusson replied, shaking his head. “Her lousy husband had a revolver—can you imagine? Pointing a gun at a woman carrying his own child.”

“Ma’am,” the boy said with sympathy.

Hadley responded with a strangled noise.

“Now, now,” Magnusson said, patting her shoulder. “Buck up, old gal. I know you say he only drinks when he’s overworked, but this can’t go on. Daddy will hire you a lawyer. It’s just not safe. You have to think of your child, now.”

“A crying shame,” the porter mumbled.

“Amen,” Magnusson agreed. “Do you think this is the stateroom they had in mind for us?”

“This one? It’s been booked by a party scheduled to board in Nevada.”

“Oh.” Magnusson’s face fell. He turned sad eyes on Hadley. “I know this is upsetting, and you’re exhausted and terrified. I’m so sorry.”

“I’ve already endured so much with you tonight . . . dear brother,” she replied dryly.

The porter cleared his throat. “I suppose the couple who booked the compartment haven’t been through your difficulties. I can put them in an open coach berth, if the two of you don’t mind sharing this compartment.”

Hadley didn’t like the sound of that, not one bit, but her protest was buried under Mr. Magnusson’s overdramatic sentiment.

“Oh, that would be wonderful. Just wonderful,” he said, flashing the porter a grateful smile as he enthusiastically pumped the man’s hand. “We’re both grateful.” He fumbled in his wallet and gave the boy a five-dollar bill. “Do you think you could do us one last favor and bring a pot of coffee and some sandwiches?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Hot tea for me, please,” she added. If they were doing this, she might as well have what she wanted.

“Yes, ma’am. Make yourselves comfortable. I’ll be right back,” the porter said, allowing them entry as he flicked the sign on the door to read OCCUPIED.

Hadley silenced her tongue and followed Mr. Magnusson inside the cramped stateroom. A small door led to a private toilet and shower on the right, and the parlor lay to the left: two cushioned seats faced each other in front of a wide picture window, capped by two pulldown sleeping berths above.

Mr. Magnusson pulled off his satchel and, along with his coat, hung his things on a hook. Then he ducked beneath the berth to plop down on one of the seats. His long body took up too much room. His shins brushed the edge of the facing seat.

“First class,” he murmured on a sigh. “I think the public berths on the 127 were stuffed with hay.”

Why on earth anyone with a bootlegging brother was riding coach was beyond her, but Hadley didn’t care to find out. As she unwound the handbag chain looped over her wrist, she addressed her bigger gripe. “First you’re on the health committee of the League, and now you’re a heroic brother to a pregnant hussy—”

“Not a hussy. I said you were married.”

“Is this what you do? Lie your way out of every situation you encounter?”

“I prefer to think of it as inventing a character. Acting.”

“Acting,” she repeated, hanging her handbag on the hook next to his satchel. She started to remove her coat, but remembered the rip in her dress. She wasn’t the only one; a slow smile crept over Magnusson’s face. She tightened the coat and perched on the facing seat. “Why wasn’t the truth good enough?”

“You mean, I should’ve told him that I’m an archaeologist who found a piece of a mythical artifact purported to open a door to the land of the dead—and two hired thugs were shooting at us to get it, so we jumped the train like hobos?”

She crossed her legs. “You, sir, aren’t an archaeologist. You’re an entrepreneur.”

“I have a degree.”

“And I have two.”

He casually kicked up his feet on the seat next to her, one ankle crossing its mate. “But no fieldwork.”

“Not for lack of wanting, but kudos for making me feel small.”

His face pinched as if she’d slapped him. But only for a moment before blankness settled over his features. He stretched his neck, loosening muscles. “You said you wanted honesty.” With his head lolling on the seat back, he rested his hands on his chest and closed his eyes. “If you’d like me to tiptoe around your feminine feelings, I’m happy to do so.”

“I want to be treated like a man.”

He glanced at her from under squinting eyelids, one brow cocked.

“I mean to say, I want to be given the same directness you’d offer a trusted colleague. I am your equal. Speak frankly to me, or not at all.” A quick anger flared inside her chest. She stared out the window, looking past her own tense reflection to the rolling black landscape.

One, two, three . . .

“All right, then,” he said after a few moments. “If you were a man, and we were colleagues, the first thing I’d do is drop the formal address.”

She hesitated. “Thank you . . . Lowe.”

“You’re welcome, Hadley.” He smiled before closing his eyes.

They sat in silence. Perhaps she’d misjudged him. Now that she had time to think about the evening’s events, she supposed some of his actions might have been well intentioned. He’d pushed her out of the first gunman’s path and defended them with the knife. He’d also shielded her from the broken glass in the first train car, not knowing she’d been the cause of it. And now that they were settled, she could admit that she’d rather be here than taking her chances back at the station.

“You know, now that I’m thinking about it,” he said with his eyes still closed, “if we were trusted male colleagues on a first-name basis with each other, I’d probably be bragging about how I just got a peek at a bea-u-tiful ass and nice pair of legs, and what a shame it was that the strange woman who curates mummified corpses in the antiquities wing of the de Young Museum dresses like an old maid.”

The nerve.

“And I’d tell you that she dresses that way so that the men she works with treat her with respect, not as the privileged daughter of Archibald Bacall.”

His voice softened. “Then I’d tell her that she shouldn’t change herself to please anyone, and her coworkers are probably overeducated Stanford graduates with no real-world field experience, so who the hell cares what they think, anyway?”

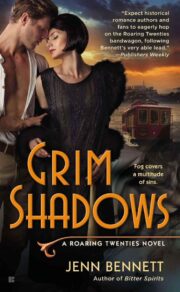

"Grim Shadows" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Grim Shadows". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Grim Shadows" друзьям в соцсетях.