Steptoe answered the door promptly. “Punctual!” he said, drawing out his watch. He held the door and we entered.

His condescending manner was enough to make me fly off the handle before I had even set foot in the room. It was a large, comfortable room that he could certainly not afford on his butler's salary. A bottle of wine sat on the bedside table, with a cheroot in a dish beside it.

"We have no time to waste, Steptoe,” I said. “If you know anything, tell us."

"Five pounds,” he said.

Mama gave an angry tsk and said, “Very well."

Steptoe stuck his fingers in his vest, waited until he had our total attention, then announced, “Lindfield."

Mama and I exchanged a surprised look. “Lindfield!” we both exclaimed together. Mama said, “But that is where-"

"Never mind, Mama,” I said quickly, before she could say more. “It is clear Steptoe knows nothing about this matter."

"I saw Barry McShane in Lindfield on two occasions,” Steptoe said, coloring up in annoyance.

"Was he wearing a clerical collar?” Mama asked.

Steptoe took it for sarcasm and said, “Certainly not! I tell you he was there. Once I followed him from Tunbridge, and once I went back when he said he was going to London, to check up on him. He went into a Tudor cottage on the High Street at ten o'clock at night, and did not come back out, though I waited for over two hours. It will be extra for the information on the house,” he said, when he realized what he had said. “Our bargain was five pounds a quarter for the name of the village."

I gave Mama a damping look, for she seemed on the verge of speech, and I did not wish her to reveal the significance of that Tudor house. “Have you not heard, Steptoe?” I asked, smiling. “Verbal contracts are not worth the air they are breathed on. Come along, Mama, we are wasting our time here. We shall expect you to be back at your post at Hernefield by noon tomorrow, or you will not receive any salary at all."

"We had a bargain,” he said angrily.

"The bargain was that you would tell us what we wished to know. My uncle did not live in that cottage. We happen to be acquainted with the owner. You may have seen him visiting our friends. That is hardly worth twenty pounds a year for the rest of your life, is it?"

I rather wished I had said nothing, but Steptoe's blush suggested he thought he had made a fool of himself. “What was the secret, then? He always let on he was going to London.” He thought a moment, then said, “He had a ladybird!"

"What of it?” I asked airily. “He was a bachelor, after all. The world will hardly condemn him for that. Let us go, Mama. Remember, Steptoe-noon tomorrow, or you may consider yourself dismissed."

We scooted out the door before he could put two and two together-that Uncle had the copy of Lady Margaret's necklace, and the lady he was visiting was Lady Margaret. Apparently Steptoe had not spotted her.

Mama and I had a long discussion of all this after we returned to our hotel. “I can see Barry visiting Lady Margaret,” Mama said, “but staying two hours? That sounds like a friendly visit."

"At ten o'clock in the evening, it sounds like a very friendly visit,” I agreed.

"Zoie, you are not suggesting that they were… paramours? You are forgetting Mr. Jones."

"Perhaps she had a paramour for each day of the week,” I said, and collapsed in mirth on the bed. “I wonder if Weylin will discover this secret when he breaks into the love nest."

"I shall die of shame!"

"And so will he."

Mama soon found new causes for worry. “It still does not explain what he did with that missing five thousand pounds."

"Perhaps he gave it to his light-o'-love-Lady Margaret."

"The waste of it! And where did he get all that jewelry he was selling, and what was he doing with the paste necklace?"

"Perhaps the jewels all belonged to Lady Margaret, and he was selling them for her. Old Macintosh was well to grass."

"I daresay that could be the answer. And Barry put on that clerical garb to fool Mr. Bradford."

"At least it has got Steptoe off our backs. How I enjoyed lighting into him."

"I cannot get over the slyness of the pair of them. You would think Barry and Lady Margaret were strangers, to see them pass on the street with a nod, and all the while they were paramours. It is odd she would choose Barry when she has a colt's tooth in her head. I am thinking of Mr. Jones."

It was indeed odd, but I felt the mystery had been solved. Even my uncle's possession of the paste necklace was now comprehensible, if not entirely clear. If he sold her jewelry for her, it could have come into his possession in some harmless way. I was in a good mood when the servant brought a note to our room at ten past eleven.

"From Lord Weylin, madam,” the servant said. “He said if your lights were out, not to disturb you. As I heard voices-"

"That is fine.” I glanced at the note, requesting us to go to the parlor if we were still dressed. “You may tell Lord Weylin we shall be down presently."

The servant left, and I said to Mama, “Weylin is back, Mama. He wants to see us. This should be interesting."

"You go, Zoie, and tell me what he has to say. I am ashamed to face him."

"I cannot imagine why. It is his aunt who had the string of lovers. Barry is relatively innocent."

"Aye, if we have heard the whole of it."

"Goose!” I said, and gave her a kiss on the cheek before running downstairs to tease Lord Weylin.

Chapter Fourteen

I found Weylin standing with his back to the door, gazing out the parlor window at the street. The door was open; he had not heard me come in. A glass of brandy sat on the table. I had not seen him drink brandy before. Indeed the hotel ought not to have had this contraband drink on the premises. I stood a moment, admiring his tall body and exquisite tailoring. His shoulders drooped, as though he were fatigued, or sad. In the dim light, his caramel hair looked black. The brandy and the weary posture suggested he was disturbed, which told me he had learned of his aunt's infamous carrying-on.

Something stirred in me. I had come with the intention of enjoying his shame, but found that I wanted to comfort him.

"Lord Weylin,” I said softly, to catch his attention.

When he turned, I saw that his expression was troubled. His eyes looked dark, his face drawn. He gazed at me a moment, then a slow smile moved his lips. It crept up to light his eyes in a warm welcome. “You came alone,” he said. “I hoped your Mama might have retired."

"She is still awake, and curious to hear if you learned anything. Bad news, was it?"

He came forward and took my hand to draw me toward the table. We sat. “No news at all, really."

I knew he was not telling the truth. His manner, his refusal to look straight at me, were as good as an admission. I put my hand on his wrist and said, “You can tell me, Weylin. I think I know the secret already. I have been speaking to Steptoe."

His other hand came out and covered mine in a firm grip. “I am sorry, Zoie. I had hoped to shield you from the sordid truth. I meant what I said earlier. There is no reason the world need know what your uncle was up to."

The womanly compassion dwindled to curiosity. “My uncle? What about your aunt? She is the one who had a lover!"

"Lover?” He looked confused. It darted into my head that he meant to deny it. “Are you referring to Mr. Jones?"

"Of course. And he is young enough to be her son."

"He was her son. That was her guilty secret. I don't know how McShane discovered it, but it is pretty clear he knew, and took advantage of it. There were letters, receipts, a deal of evidence that McShane had been extorting money from my aunt."

I snatched my hand back. “I don't believe it! You are making that up to hide her shame."

"An illegitimate child is hardly less shameful than having a lover,” he said crossly.

I did not really care if Lady Margaret had a whole platoon of illegitimate children. What vexed me was that he had turned Barry back into a scoundrel, just when I thought we had reclaimed him to relative respectability. “What did you find?"

Weylin put a little heap of papers on the table and began passing them to me, one at a time. The first was a letter from Ireland dated five years before, written during my uncle's short trip home, before coming to live at Hernefield. I read:

Dear Margaret: While in Dublin I chanced to meet Andrew Jones. The name, perhaps, will be familiar to you? He is twenty-five years old. He was teaching in a poor boys’ school here, and living in abominable conditions. I looked into his history, and know the truth, so do not try to deny it. He seems a very nice, modest lad. I am shocked that you should treat him so badly. Remember that, whatever of his papa, from his mama he carries noble Weylin blood in his veins.

I am bringing him to England. Something must be done to better his condition. I shall not embarrass you by making public what you have done, but I must insist on repairing the damage to the extent possible. There is no reason your family need be aware of it. I shall visit my sister, Mrs. Barron, who lives near Parham. You need not publicly recognize him or me, but we must meet and decide what is to be done about Andrew. I shall contact you when I arrive. I trust we can handle this matter amicably. Sincerely, B. J. Barron.

I wanted to take the letter and fling it into the grate, to hide from the world my uncle's despicable trick. He had ferreted out Lady Margaret's shameful secret and used it to put her under his power. Without a word, Weylin handed me another letter. It was addressed a week later. I read:

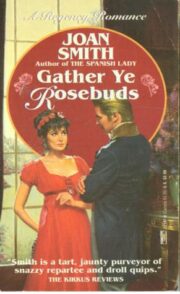

"Gather Ye Rosebuds" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Gather Ye Rosebuds". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Gather Ye Rosebuds" друзьям в соцсетях.