“Well, by God!” said Sherry, quite thunderstruck.

She tried to smile. “How odious you are! You may imagine how deeply I am in disgrace with Mama. The only person, except poor Papa, who has been kind is your mother, and that is in part why I am going with her to Bath. To be open with you, Sherry, I believe she has taken a foolish notion into her head that you may divorce poor little Hero, and end by marrying me after all.”

“Well, I shan’t,” said his lordship, with an entire absence of gallantry.

“Don’t flatter yourself I would accept you!” retorted Miss Milborne. “I care no more for you than I cared for Severn! Well, yes, perhaps a little more, but not very much!”

“I wish I knew who it is you do care for!” said Sherry.

She turned her face away. “I had thought you did know. If you do not, I am glad.”

“George?” Then, as she made no answer, he said: “Of all the stupid coils! George took such a pet over you that there’s no doing a thing with him these days. Riding as hard as he can to the devil. You’d best stay in London, Bella!”

“No,” she replied. “I should not dream of doing so. George may think me what he wills: I shall go to Bath with Lady Sheringham.”

“Don’t you! It’s a rubbishing place: can’t stand it myself!” He stopped abruptly, his brows snapping together, his eyes holding an arrested expression. “Bath! When was I talking of the place last? Said I should be obliged to go there if — Great God, why did I never think of that before? Bath — school — governess! That’s what she’s done, the little fool, the little wretch! My Kitten! Some damned Queen’s Square seminary, you may lay your life, and very likely turned into a drudge for a parcel of — Tell my mother I’ll escort her to Bath with the greatest pleasure on earth, but she must be ready to start tomorrow!”

“Sherry!” she gasped. “You think Hero may be there?”

“Think! I’m sure of it! If I weren’t a rattle-pated gudgeon I should have thought of it weeks ago! Tell you what, Bella, if we mean to keep my mother in a good humour, we’d best say nothing about this. Let her suppose you persuaded me: it don’t make a ha’porth of odds to me, but she can be deuced unpleasant if things don’t go the way she wants, and if you’re to be cooped up in a coach with her for two days — for she’ll never consent to do the journey in one! — you’ll get a trifle tired of the vapours!”

And with this piece of sound, if undutiful, advice, his lordship caught up his coat and hat and strode off to make his arrangements for an instant departure from town.

Chapter Twenty

WHILE THESE EVENTS WERE IN PROGRESS, Hero was residing in Upper Camden Place, Bath, the guest of Lady Saltash. At first a little frightened of an old lady who was generally held to be both formidable and sharp-tongued, she had soon settled down, and quite lost her shyness. The pug, not being as yet gathered to its fathers, was her particular charge; in addition to brushing this stertorous animal, and taking it for walks on the end of a leash, she played cribbage with her hostess, read to her from the newspapers, and accompanied her to the Grand Pump Room, or to the Assembly Rooms, where her ladyship was a subscriber to the Card and Reading Rooms. She had removed her wedding ring and reverted to the use of her maiden name, two proceedings which drew an approving nod from Lady Saltash. It was at first difficult to remember that she was again Miss Wantage, and when Lady Saltash took her to one of the Dress Balls at the New Assembly Rooms she drew shocked eyes upon herself by moving unconsciously towards the benches set aside for the use of peeresses. But this little slip was easily glossed over, and as soon as the Master of Ceremonies had been presented to her, and had signified his approval of Lady Saltash’s young protégée, her social comfort was assured. In the nature of things, she cared little for this, and would have been glad to have lived the life of a recluse would Lady Saltash but have permitted it. But Lady Saltash had no opinion of recluses, and she gave Hero some very good advice about never being led into the error of wearing one’s heart upon one’s sleeve.

“Depend upon it, my love, nothing is more tiresome than the person who is for ever bemoaning her fate. Recollect that no one has the smallest interest in the troubles of another! To be shutting yourself up because you fancy your heart is broken will not do at all. Do not wear a long face! As well heave sighs, than which nothing could be more vulgar!”

Hero promised to do her best to be cheerful, but said that it was sometimes hard to smile when she was so very miserable.

“Fiddle-de-dee!” replied Lady Saltash. “When you have had as much cause as I to talk of being made miserable you may do so, but believe me, my love, you know nothing of the matter as yet, and very likely never will. From what you have told me, you have not the least need to put yourself into a taking. I have known Anthony any time these twenty years, and you have gone the right way to work with him. I dare say he may be tearing out his hair by the roots by this time!”

“But I never, never meant him to be made unhappy or anxious!” Hero exclaimed, looking quite oppressed.

“Very like you did not. You are a silly little puss, my love. My grandson has more sense, it appears, for he certainly means Anthony to be excessively anxious.”

“Oh, he must not! That would be worse than all the rest!” Hero cried distressfully.

“Nonsense! It is high time that boy was made to think, which I’ll be bound he has never done in his life. I do not scruple to tell you, my love, that I have been agreeably surprised by what you have told me. It appears that Anthony has behaved towards you with more consideration that I should have expected in one reared to consider nothing but his own convenience. I dare swear he has been in love with you all this while without having the least notion of it. It will do him a great deal of good to miss you.”

Hero regarded her hopefully. “Do you think so indeed, dear ma’am? But perhaps you do not perfectly understand that he only married me because Isabella Milborne refused to accept his hand?”

“Do not talk to me about this Miss Milborne! She sounds to me just the insipid sort of girl who passes for a beauty in these days! Now, when I was young — However, that’s neither here nor there! I shall be surprised if we find that Anthony cares a fig for her. Soon or late, mark my words! we shall have him posting down here to find you, and I will tell you now, my child, that if you mean to let him discover you halfway to a decline, I shall wash my hands of you! That is no way to handle a man. A little jealousy will work wonders with that boy: he has been too sure of you! I must tell you, my love, that these Verelsts are all the same! Like Pug there! Let no one wish to touch his bone, and ten to one he will not look at it. Lay but a finger on it, and all at once he knows that there is nothing he wants more in the world, and he will snarl, and show his teeth, and stand guard over it with all his bristles on end! I am determined that if Anthony comes to look for you, he shall find you living in tolerable comfort without him.”

Hero looked doubtful, but the idea of Sherry’s coming to look for her was so precious to her that she raised no further demur at the programme outlined for her by her worldly-wise hostess.

Mr Ringwood, though not generally held to be a good correspondent, wrote with painstaking regularity, reporting on Sherry’s progress. Hero shed tears in secret over these letters, and had she not made up her mind to allow Sherry time to forget her, if he should wish to do so, she would have written to set his mind at rest at least a dozen times. When she heard that he had plunged into an orgy of gaiety, she really did feel as though her heart must break, and believed that he had ceased to grieve over her disappearance. When she could command her voice, she sought out Lady Saltash, and tried, for the third or fourth time, to broach the question of her applying for a post in a Young Ladies’ Seminary.

Her ladyship cut her short. “Don’t put on those missish airs with me, Hero! What has happened to make you start on that nonsense again, pray?”

“Only that I have had a letter from Gil, ma’am, which — which — ’’

Her ladyship held out an imperative hand, a little twisted by gout. After a moment’s hesitation, Hero gave up the letter. Lady Saltash read it with an unmoved countenance. “Going to the devil, is he?” she commented. “Very likely. Just as I expected! Pray, what is there in this billet, beyond the lamentable spelling, to make you pull that long face?”

“Don’t you think Sherry is forgetting all about me, ma’am?” Hero asked wistfully.

“What, because he is behaving like a sulky boy? No such thing! He is determined no one, least of all yourself, my love, shall guess how much he cares. Really, I begin to have hopes of that tiresome boy! Put the letter up, my dear, and think no more of it! I apprehend we might find the piece they are playing at the Theatre Royal tolerably amusing. Have the goodness to sit down at my desk, and write two little notes, inviting Sir Carlton Frome and Mr Jasper Tarleton to do me the honour of accompanying me there tomorrow evening. We will send one of the servants round to procure a box for us.”

Hero obeyed her. She paused in the middle of her task to look up, and to say: “After all, if Sherry may amuse himself I do not know why I should not too!”

“Excellent!” said her ladyship, laughing. “Do you mean to break Mr Tarleton’s heart? I wish you may do it!”

Hero gave a chuckle. “Why, he is quite old, ma’am!”

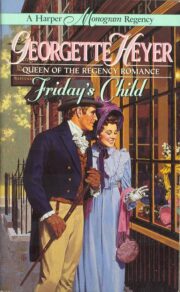

"Friday’s Child" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Friday’s Child". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Friday’s Child" друзьям в соцсетях.