“Yes, she can,” said Mr Ringwood unexpectedly. “At least, not for long, but no reason why she shouldn’t stay here tonight. In fact, she must.”

“Good God, Gil, you must have taken leave of your senses!” said George explosively. “No reason why she shouldn’t, indeed! If that’s all your precious thinking leads to — ”

“No reason at all,” said Mr Ringwood. “Got her abigail. Have a truckle bed put up in my room. I’ll spend the night in your lodging.”

“I suppose she could do that,” George admitted grudgingly. “But it don’t solve anything! Dash it, it’s the damnedest coil! She has no relatives she may go to, or I’d say she was right to leave Sherry. But she can’t live by herself! You know that! If her mother-in-law weren’t such a curst disagreeable woman — You are certain you could not bear to go to Sheringham Place, Kitten? I mean, Sherry’s a brute to have put it to you like that, but I can’t but see what’s in his head. It is the dowager’s business to have an eye on you, only — ”

“No, no, George, pray do not ask me to go there!” Hero begged him. “I have made up my mind that I will become a governess, just as Cousin Jane always said I should be. But I do not know how to set about it, and that is why I came to Gil, because he taught me to drive my phaeton, and I thought he might know.”

“Do you know, Gil?” inquired Ferdy, looking at Mr Ringwood with dawning respect.

“No,” replied Mr Ringwood.

“Didn’t think you would,” said Ferdy. “Tell you what: ask my mother! Bound to know!”

“She ain’t going to be a governess,” said Mr Ringwood shortly. “Told you I’d been thinking. Well, I’ve got a notion.”

George, who had been turning the matter over in his mind, said suddenly: “It’s all very well, but she can’t leave Sherry like this! Dash it, it’s impossible!”

“No, it ain’t,” replied Mr Ringwood, his stolidity unshaken. “Best thing she could do. Going to take her to stay with my grandmother.”

“By Jove!” exclaimed Ferdy, much struck. “Devilish good notion of yours, Gil! As long as she ain’t dead.”

“Of course she ain’t dead!” said Mr Ringwood, with a touch of impatience. “How could I take Kitten to stay with her if she was?”

“That’s what I was wondering,” confessed Ferdy. “Thought she was dead. Thought you went to the funeral, what’s more.”

“If you weren’t so cork-brained you’d know that was my other grandmother!” said Mr Ringwood, quite exasperated. “I’m talking of my maternal grandmother, Lady Saltash.”

Ferdy regarded him fixedly. “Forgot she was your grandmother too. You know what I think, Gil?”

“No, and I don’t want to.”

“No need to get into a miff, dear old boy! Only going to say, couldn’t have had a better notion myself. Very sporting old lady, your grandmother. Dare say she and Kitten may deal extremely.”

“Oh, do you think she would be so obliging as to teach me how to behave like a lady of fashion?” Hero asked anxiously.

“Shouldn’t be at all surprised,” responded Mr Ringwood. “Never met any old lady so much up to snuff as my grandmother.”

A qualm smote Hero; she said: “But perhaps she may not like to have me to stay with her, Gil?”

“Yes, she will. Like it above all things. Dare say you may be very useful to her. Got a pug-dog. Nasty, smelly little brute. Took a piece out of my leg once. You could take it for walks. Wants exercising. At least, it did when I last saw it. Of course, it may be dead by now. Good thing if it is.”

Ferdy, who had been listening attentively, interposed at this point to object: “Don’t see that, Gil, old boy; don’t see that at all! Stands to reason Kitten can’t take the pug for walks if it’s dead. No point in her going to Bath.”

“Bath! Does she live in Bath?” cried Hero, before the incensed Mr Ringwood could wither Ferdy. “Oh, nothing could be better: for it was to Bath I was to have gone to be a governess, and Sherry does not like the place, and he will never look for me there! Oh, Gil, how kind and clever you are!”

Mr Ringwood blushed and disclaimed. Ferdy agreed that Gil had always been a knowing one, and only George remained unconvinced. But he reserved his criticisms until Hero and her abigail had presently been escorted upstairs by Mr Ringwood’s impassive valet. He then spoke his mind in no uncertain fashion, the gist of his argument being that whatever the state of affairs might be between Sherry and his wife, they were legally married, and it was the height of impropriety for Gil or anyone else to aid and abet Hero in deserting her husband.

“I don’t care a fig for that,” responded Mr Ringwood. He had by this time changed his dressing-gown for a blue coat and a waistcoat, and was engaged in stuffing into a cloak-bag such items as he might be supposed to need for a night’s sojourn away from home.

“I dare say you don’t,” retorted Lord Wrotham, “but you’re not the only one of us who can think, let me tell you! I don’t mean Ferdy: I know he can’t; but I can, and what’s more, I have thought! I’m devilish fond of Kitten, but dash it, Sherry’s a friend of mine!”

“Friend of mine too,” said Mr Ringwood, finding a snug resting-place for his hairbrushes inside a pair of bedroom slippers.

“Well, if he’s a friend of yours, you’ve no business to hide his wife from him!”

“Yes, I have. Been thinking of it for a long time.”

“Thinking of hiding Kitten for a long time?” demanded Lord Wrotham incredulously.

“You’re a fool, George. Big a fool as Ferdy. Been thinking about Sherry and Kitten. Fond of ’em both.”

“I’m fond of them both too,” said Ferdy. “What’s more, Sherry’s my cousin. But he’s got no right to behave like a curst brute to Kitten. Cousin or no cousin. Dear little soul! Dash it, Gil, almost an angel!”

“No,” said Mr Ringwood, after thinking this over. “Not an angel, Ferdy. Dear little soul, yes. Angel, no!”

“It don’t matter what she is!” struck in George. “All that signifies is that she’s Sherry’s wife!”

Mr Ringwood looked at him under his brows, but refrained from comment. After a slight pause, George said: “Not our affair, whatever we may think. The fact of the matter is, she does need some older female to school her.”

“She’ll have one,” replied Mr Ringwood.

“Yes, that’s all very well, but though I don’t say he set about it the right way, Sherry ain’t so far wrong when he takes it into his head to send Kitten down to the dowager.”

“Do you know my aunt Valeria, George?” asked Ferdy, astonished.

“Oh, lord, yes, I know her! But — ”

“Well, I wouldn’t have thought it.”

“That ain’t the point,” interrupted Mr Ringwood. “Point is what Kitten said just now: Sherry don’t love her.”

“I wouldn’t say that, Gil,” protested Ferdy. “Never told me he didn’t love her!”

Mr Ringwood closed his cloak-bag and strapped it. “I know Sherry,” he said. “But I don’t know if he loves Kitten or not. Going to find out. If you ask me, he don’t know either. If he don’t it ain’t a particle of use sending Kitten to the dowager. Come to think of it, it ain’t much use sending her there if he does, because that ain’t the way he’d find it out. But if he does love her, he ain’t going to like not knowing what’s become of her. Might miss her like the devil. Make him start to think a trifle.”

George regarded him frowningly. “Are you going to tell Sherry you don’t know where his wife is?”

“Not going to tell him anything,” said Mr Ringwood. “He won’t think I had anything to do with it. Thought it all out. You’re going to tell Sherry I’ve gone off to Hertfordshire, because that uncle of mine looks like dying at last.”

“I’ll tell him, if George don’t like to,” offered Ferdy.

“No, you won’t,” answered Mr Ringwood. “You’re coming to Bath with me.”

“No, dash it, Gil!” feebly protested Ferdy.

George, whose brow had cleared, said: “By God, I believe you’ve hit it, Gil! Damme, I’ve thought for a long time Sherry needed a lesson! I will tell him you’ve gone to Hertfordshire! Yes, by Jove, and I’ll take precious good care he don’t ask me if I know what’s become of his Kitten!”

“Yes, but I don’t want to go to Bath!” said Ferdy.

“Nonsense! Of course you’ll go!” George said briskly. “You can’t leave poor old Gil to bear the brunt of it! Besides, it’ll look better if you both escort Kitten. You know what Sherry is! Why, he even called me out, only for kissing her! If he got to hear of Gil’s jauntering about the country with her he’d very likely cut his liver out and fry it. Can’t take exception to the pair of you going with her.”

When the matter was put to him like that, all Ferdy’s chivalrous instincts rose to the surface, and he at once begged pardon, and said that he would stand by Gil to the death. Upon reflection, he admitted that he would as lief not meet his cousin Sherry on the following day. George then wished to be assured that Mr Ringwood’s man, Chilham, was to be trusted to keep his mouth shut, and upon being told that he was the most discreet fellow alive, said that there seemed to be nothing more to do in the matter until the following day. All three gentlemen thereupon left the house, Ferdy going off to Cavendish Square and Mr Ringwood, his cold forgotten, accompanying George to his lodgings in Ryder Street.

Chapter Nineteen

WHEN HERO PUT IN NO APPEARANCE AT THE breakfast table next morning, the Viscount was not much surprised, and he made no comment. He himself had passed an indifferent night. His visit to White’s, on the previous evening, had confirmed his worst fears. One tactless gentleman had actually had the effrontery to mention Hero’s projected race to him, and instead of landing this person a facer he had been obliged to treat the matter lightly, saying that it was all a hum, and that he wondered that anyone could have been green enough to have supposed that it could have been anything else. After that he had gone home, and had written a stiff note to Lady Royston, cancelling the meeting. That had taken him an hour to compose, and he had wasted a great many sheets of paper on it, and had not even the satisfaction of feeling that the final copy conveyed his sentiments to the lady. Unquiet dreams had disturbed his sleep, and he arose in the morning not in the least refreshed, but more determined than ever to remove Hero from London until such time as the Polite World had forgotten her lapse from grace. His lordship was not going to run the risk of his wife’s being refused a voucher for Almack’s; and, to do him justice, this caution was more on her behalf than on his own. He made up his mind to explain it all carefully to Hero on the way down to Kent, for although he had been extremely angry with her on the previous evening, he was not one to nurse rancour, and he was already sorry that he had left her room so precipitately, and without comforting her distress, or making any real attempt to alleviate her alarms. He did not like to think of his Hero in tears, and he was much afraid that she had cried herself to sleep. When she did not come down to breakfast, he was sure of it. So as soon as he had finished his own repast he went up to her room and knocked politely on the door. There was no answer, and, after waiting for a moment, he turned the handle and walked in. The room was in darkness. Surprised, he hesitated for an instant before speaking his wife’s name. There was again no answer. All at once the Viscount felt, without quite knowing why, that there was no one but himself in the room. He strode over to the window, and flung back the curtains, and turned. No erring wife lay sleeping in the silk-hung bedstead. The quilt had not even been removed from it, but on one pillow lay a sealed billet.

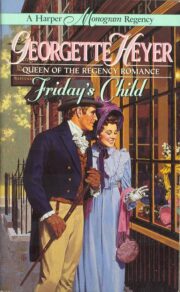

"Friday’s Child" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Friday’s Child". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Friday’s Child" друзьям в соцсетях.