For the rest, although he might lack polish, he proved to be the most devoted servant the Viscount had ever hired. No slave could have been less critical of his owner’s vagaries, or more tireless in his attentions. He had been overturned in his lordship’s curricle five times; had had his leg fractured by a kick from a half-broken horse; had accompanied the Viscount on some of his more hazardous expeditions; and was generally supposed to be willing to engage on his behalf on any enterprise, inclusive of murder.

As he hung on to the straps of the curricle behind the Viscount, he observed dispassionately that he knew all along that they wouldn’t stay above two days in that ken. Receiving no answer to this remark, he relapsed into silence breaking it only at the end of a mile to recommend his master to pull in for the corner, unless he was wishful to throw them both out on to their bowsprits. His tone indicated that if the Viscount had any such wish he was prepared cheerfully to endure this fate.

However, the Viscount, having had time to work off the first heat of his rage, steadied his pair, and took the corner at no more than a canter. The main road to London lay a couple of miles farther on, the lane that led to it from Sheringham Place winding alongside the Viscount’s acres for some way, and then curling abruptly away to serve a small hamlet, one or two scattered cottages, and the modest estate owned by Mr Humphrey Bagshot. Mr Bagshot’s house was set back from the lane and screened by trees and a shrubbery, the whole being enclosed by a low stone wall. The Viscount, whose attention was pretty equally divided between his horses and his late disappointment, kept his moody gaze fixed on the road ahead, and would not have spared a glance for this wall had not his Tiger suddenly recommended him to cast his daylights to the left.

“There’s a female a-wavin’ at you, guv’nor,” he informed his master.

The Viscount turned his head, and found that he was sweeping past a lady who was perched on top of the wall, somewhat wistfully regarding him. Recognizing this damsel, he reined in, backed his pair, and called out: “Hallo, brat!”

Miss Hero Wantage seemed to find nothing amiss in this form of salutation. A little flush mounted to her cheeks; she smiled shyly, and responded: “Hallo, Sherry!”

The Viscount looked her over. She was a very young lady, and she did not at this moment appear to advantage. The round gown she wore was of an unbecoming shade of pink, and had palpably come to her at secondhand, since it seemed to have been made originally for a larger lady, and had been inexpertly adapted to her diminutive size. A drab cloak was tied round her neck, its hood hanging down over her shoulders; and in her hand she held a crumpled and damp handkerchief. There were tear-stains on her cheeks, and her wide grey eyes were reddened and a little blurred. Her dusky ringlets, escaping from a frayed ribbon, were tumbled and very untidy.

“Hallo, what’s the matter?” asked the Viscount suddenly, noticing the tear-stains.

Miss Wantage gave a convulsive sob. “Everything!” she said comprehensively.

The Viscount was a good-natured young man, and whenever he thought of Miss Wantage, which was not often, it was with mild affection. In his graceless teens he had made use of her willing services, had taught her to play cricket, and to toil after him with the game-bag when he went out for a little hedgerow shooting. He had bullied her, and tyrannized over her, lost his temper with her, boxed her ears, and forced her to engage in various sports and pastimes which terrified her; but he had permitted her to trot at his heels, and he had allowed no one else to tease or ill-treat her. Her situation was not a happy one. She was an orphan, taken out of charity when only eight years old to live in her cousin’s house, and to be brought up with her three daughters, Cassandra, Eudora, and Sophronia. She had shared their lessons, and had worn their outgrown dresses, and had run their numerous errands — such services being, her Cousin Jane informed her, a very small return for all the generosity shown her. The Viscount, who disliked Cassandra, Eudora, and Sophronia only one degree less than he disliked their Mama, gave it as his considered opinion, when he was fifteen years old, that they were brutes, and treated their poor little cousin like a dog. He had therefore no difficulty now, as he looked at Miss Wantage, in interpreting correctly her somewhat sweeping statement. “Those cats been bullying you?” he said.

Miss Wantage blew her nose. “I’m going to be a governess, Sherry,” she informed him dolefully.

“Going to be a what?” demanded his lordship.

“A governess. Cousin Jane says so.”

“Never heard such nonsense in my life!” said the Viscount, slightly irritated. “You aren’t old enough!”

“Cousin Jane says I am. I shall be seventeen in a fortnight’s time, you know.”

“Well, you don’t look it,” said Sherry, disposing of the matter. “You always were a silly little chit, Hero. Shouldn’t believe everything people say. Ten to one she didn’t mean it.”

“Oh yes!” said Miss Wantage sadly. “You see, I always knew I should have to be one day, because that’s why I learned to play that horrid pianoforte, and to paint in water-colours, so that I could be a governess when I was grown-up. Only I don’t want to be, Sherry! Not yet! Not before I have enjoyed myself just for a little while!”

The Viscount cast off the rug which covered his shapely legs. “Jason, get down and walk the horses!” he ordered, and sprang down from the curricle and advanced to the low wall. “Is that mossy?” he asked suspiciously. “I’m damned if I’ll spoil these breeches for you or anyone else, Hero!”

“No, no, truly it’s not!” Miss Wantage assured him. “You can sit on my cloak, Sherry, can’t you?”

“Well, I can’t stay for long,” the Viscount warned her. He hoisted himself up beside her and put a brotherly arm round her shoulders. “Now, don’t go on crying, brat: it makes you look devilish ugly!” he said. “Besides, I don’t like it. Why has that old cat suddenly taken it into her head to send you off? I suppose you’ve been doing something that you shouldn’t.”

“No, it isn’t that, though I did break one of the best teacups,” said Hero, leaning gratefully against him. “It’s partly because Edwin kissed me, I think.”

“You’re bamming me!” said his lordship incredulously. “Your wretched little cousin Edwin hasn’t got enough bottom to kiss a chambermaid!”

“Well, I don’t know about that, Sherry, but he did kiss me, and it was the horridest thing imaginable. And Cousin Jane found out about it, and she said it was my fault, and I was a designing hussy, and that she had nourished a snake in her bosom. But I am not a snake, Sherry!”

“Never mind about that!” said Sherry. “I can’t get over Edwin! If it don’t beat all! He must have been foxed, and that’s all there is to it.”

“No, indeed he wasn’t,” said Hero earnestly.

“Then it just shows how you can be mistaken in a man. All the same, Hero, you shouldn’t let a miserable, snivelling fellow like that kiss you. It’s not the thing at all.”

“But how could I prevent him, Sherry, when he caught me, and squeezed me so tightly that I could scarcely breathe?”

The Viscount gave a crow of laughter. “Lord, only to think of Edwin turning into such an out-and-outer! It seems to me I had best teach you a trick or two to counter that kind of thing. Wonder I didn’t do it before.”

“Thank you, Sherry,” said Hero, with real gratitude. “Only now that I am being sent to be a governess in a horrid school in Bath, I don’t suppose I shall need any tricks.”

“It’s my belief that it’s all a hum,” declared Sherry. “You don’t look like any governess I’ve ever seen, and I’ll lay you odds no school would hire you. Do you know anything, Hero?”

“Well, I didn’t think I did,” replied Hero. “Only Miss Mundesley says I shall do very well, and it is her sister who has the school, so I dare say it has all been arranged between them. She is our governess, you know. At least, she used to be.”

“I know,” nodded Sherry. “Sour-faced old maid she was, too! I’ll tell you what, brat: if you go to this precious school they’ll make you a damned drudge, and so I warn you! Come to think of it, what the devil are they about, turning a chit like you upon the world?”

“Miss Mundesley says I shall be very strictly taken care of,” said Hero. “They are not turning me upon the world, exactly.”

“That’s not the point. Damme, the more I come to think of it the worse it is! You’re not a pauper brat!”

Miss Wantage raised her innocent eyes to his face. “But that is what I am, Sherry. I haven’t any money at all.”

“That don’t signify,” said the Viscount impatiently. “What I mean is, females of your breeding aren’t governesses! Never knew your father myself, but I know all about him. Very good family — a curst sight better than the Bagshots! What’s more, you’ve got a lot of damned starchy relations. Norfolk, or some such place. Heard my mother speak of them. Sounded to me like a very dull set of gudgeons, but that’s neither here nor there. You’d better write to them.”

“It wouldn’t be of any use,” sighed Hero. “I think my father quarrelled with them, because they wouldn’t do anything for me when he died. So I dare say they wouldn’t object to my becoming a governess at all.”

“Well, I do,” said the Viscount. “In fact, I won’t have it. You’ll have to think of something else.”

Miss Wantage saw nothing either arbitrary or unreasonable in this speech. She agreed to it, but a little doubtfully. “Marry the curate, do you mean, Sherry?” she asked, slightly wrinkling her short nose.

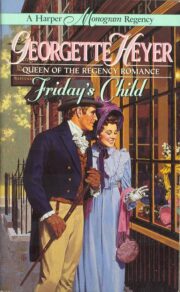

"Friday’s Child" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Friday’s Child". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Friday’s Child" друзьям в соцсетях.