“What?” gasped Sherry.

George nodded. “Yesterday morning. You know, Sherry, you ought to keep an eye on your Kitten. Not my business, but she’s such a baby there’s no knowing what she’ll do next. Came to beg me not to meet you.”

“If that isn’t like Kitten!” exclaimed Sherry. “You know, George, there’s no keeping pace with her at all! How was I to guess I ought to have warned her to take a hackney, if she meant to call at a man’s lodgings?”

George looked a trifle startled, and said: “The point is she ought not to call at a fellow’s lodgings, old boy.”

“No, by Jove, she ought not!” agreed Sherry. “Devil of a business being married, George! You’ve no notion! Never thought I should be kept so busy, but what with the Royal Saloon, the Peerless Pool — yes, I was only in the very nick of time to stop her going off there! — Bartholomew Fair, and now this, not to mention a few other starts — dash it, I don’t have a quiet moment!”

“She don’t mean a bit of harm, Sherry,” said George awkwardly.

“Oh, lord, no! The thing is, she ain’t up to snuff yet, and that cousin of hers never put her in the way of things.”

George feather-edged a corner before saying: “I dare say she wouldn’t do anything she thought you might not like. Devilish fond of you, Sherry.”

“Yes, I’ve known her since she was eight years old, you see,” responded Sherry, with an unconcern that effectually silenced his friend.

While these events had been taking place, Hero had received an early morning visit from Miss Milborne, who was ushered into the dining-room before the breakfast dishes had been removed from the table. She was looking rather pale, and she bore herself with something less than her usual poise. Without pausing to apologize for calling at so unseasonable an hour, she said impetuously: “You were right! I have not been able to sleep for thinking of it! Indeed I did not mean to be so disobliging! I will do what I may to dissuade Wrotham from engaging in this affair!”

There was not a particle of malice in Hero’s nature, and she responded at once with the sunniest of smiles, and a warm handclasp. “Oh, I knew I could not be mistaken in you, Isabella! I am very much obliged to you, only it is too late, for they went off some hours ago to Westbourn Green. I cannot imagine what can be detaining them so long!”

Miss Milborne stared at her in horror. “They have gone? And you can sit here, eating your breakfast, as though — And you called me heartless!”

Hero gave a little chuckle. “Oh, but there is nothing to be worried about! George promised me he would not hurt a hair of Sherry’s head. He said he would fire in the air, so I can be quite comfortable, you see!”

“And what,” asked Miss Milborne, in a strangled voice, “if it is Sherry who kills George?”

“Well, I thought of that, too,” admitted Hero. “But George assured me Sherry could not hit him at twenty-five yards, and I expect he must know. Do let me give you some coffee, Isabella!”

“Thank you, no. I collect that you actually called on Wrotham at his lodging?”

“Yes, for what else could I do, when you would not help me? And, indeed, I am very sorry that I troubled you, Isabella, for there was not the least need: George told me instantly that I need have no fear for Sherry. And Gil said I must particularly request you not to mention the matter to a soul, and I forgot to do so.”

“Make yourself easy on that score: I should not think of prattling upon such a subject!” Miss Milborne said, in a colourless tone. “I must not stay. I am happy to know that my intervention was not needed.”

Hero perceived that she had in some way erred, and said nervously: “No, but — but I do hope you do not think — George said that he had not the least notion of killing Sherry, you see, so perhaps my intervention was not needed either.”

“Very likely,” said Miss Milborne. “It is a case of all’s well that ends well, in fact.”

“Yes, only — Isabella, pray do not be thinking that George cares a button for me, for nothing could be more nonsensical!”

Miss Milborne gave a tinkling little laugh. “My dear, if I trust that he does not it is quite for your own sake, I assure you! It is nothing to me whom he cares for. Now, indeed, I must go, for I have to drive out presently with Mama! We shall meet at Almack’s, I dare say. Do you go to the Cowpers’ party? I need not ask, however! all the world and his wife will be there, I collect!”

Hero was so much quelled by this bright manner that she could summon up no more courage than sufficed to allow her to escort her friend to the front door, and bid her a somewhat faltering farewell. She began to be much afraid that she had done poor George a very ill turn; and until the sound of Sherry’s step in the hall banished any but the most cheerful thoughts she sat wondering how she could best set matters to rights for that ill starred lover.

Sherry came cheerfully in, and, as she jumped up, took her by the shoulders and shook her, not very hard, saying: “Kitten, you little wretch, how dared you ask George not to blow a hole through me?”

“But I did not wish him to blow a hole through you, Sherry!” she replied reasonably. “What else could I do? Only I am afraid I have made Isabella very angry, and I don’t know what to do!”

“What the deuce has Isabella to say to anything?” he demanded.

“Well, you see, I asked her if she would speak to George, but she — she did not seem to understand any more than you did how George came to kiss me, and she would not do it, and now she is — ”

“You asked Isabella to intercede with George for me?” gasped Sherry, the indulgent grin wiped suddenly from his face.

She raised a pair of dismayed eyes. “Oh, dear, perhaps I should not have mentioned that! Please do not mind it, Sherry!”

“Not mind it! Do you know that you have done your best to make me the laughing stock of the town?”

“Oh, no, Sherry, truly not! Isabella was not in the least amused, I assure you!”

He looked very hard at her. “Did Gil and Ferdy set you on to do it?”

“No, no!” she said hastily. “It was quite my own idea!”

“You deserve I should box your ears!”

“No, pray do not!” she said earnestly. “Isabella will not speak of the matter: she said she should not! But, Sherry, I fear she believes that he has been flirting with me! Would you be so very obliging as to tell her that it was no such thing?”

“No, by Jove, I will not!” he declared. “Upon my word, what next will you ask me to do?”

“But if she knew that you do not mind George’s having kissed me — ”

“But I do mind!” said Sherry, incensed.

“Do you, Sherry?” she asked wistfully.

“Well, of course I do! A pretty sort of a fellow I should be if I did not!”

“I won’t do it again,” she promised.

“You had better not, by Jupiter! And while I think of it, brat, you are not to visit men’s lodgings again either!”

“I do know that, Sherry, but it was so very awkward, on account of George’s not liking to come to this house, that I did not see what else I could do.”

“That’s all very well,” responded Sherry severely, “but you shouldn’t have gone there in your own carriage. Don’t you know enough to take a hackney upon such an occasion?”

“I never thought of that!” she said innocently. “How stupid of me it was! I shall know better another time. I am so glad I have you to tell me these things, Sherry, for Cousin Jane never told me anything to the point.”

It occurred to his lordship that the piece of worldly wisdom he had imparted to his bride was not in the least what he had meant to say, but after all the excitements of the morning he did not feel capable of entering more fully into the ethical and moral aspects of what he knew to have been a perfectly harmless visit to George’s lodging. He said that she was on no account to do it again, and abandoned the whole topic.

The relief he had felt when George had deloped on the ground had been considerable, and not even a visit from his man of business availed to subdue a mood of somewhat riotous optimism. His lordship was strongly of the opinion that he would shortly come about, since it was absurd to suppose that a run of ill luck could last for ever. Mr Stoke, unable to share his employer’s sanguine belief, was obliging enough to cite a depressing number of cases in refutation of it; but the Viscount, having listened with a good deal of impatience to the horrid tale of the gentleman of fortune who, having lost even the coat upon his back at play, hanged himself from a street lamp, while his late opponent waited to collect his coat when he should have done with it, triumphantly produced in defence of his theory the evidence of his having only three days since backed the winner in a race between a turkey and a goose. He was, indeed, slightly taken aback when he read the sum of his obligations, and agreed that to be continually selling out his holding in the Funds would be a dashed bad thing.

“And the next step, as, I am persuaded, I need hardly point out to your lordship,” said Mr Stoke gently, “will be the sale of your lands.”

The Viscount had upon more than one occasion stated his dislike of Sheringham Place, and he had not, so far, betrayed the smallest sign of taking more than a perfunctory interest in the management of his considerable estates, but at these words a sudden flash came into his blue eyes, and he exclaimed involuntarily: “Sell my land? You must be mad to think of it! I will never do so!”

Mr Stoke looked thoughtfully at him, his expression of close interest at odd variance with the meekness of his tone as he said: “After all, your lordship does not care for Sheringham Place.”

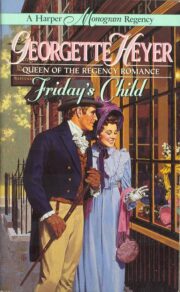

"Friday’s Child" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Friday’s Child". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Friday’s Child" друзьям в соцсетях.