“Do you think he may not have liked it?” Hero asked anxiously. “He is such a particular friend that I thought I might say what I pleased to him. And I did want to know, because you said that everyone had them, and — ”

“Oh, my God, the things I say!” groaned Sherry. “I wish you will forget them, brat! and as for my opera dancer, that is all over and done with now that I am a sober married man, so let us have no more talk of it!”

“I won’t say another word,” promised Hero, brightening perceptibly. “Can you not have them if you are married?”

The Viscount laughed and tossed a bill across the table. “Not if you have a wife who spends as much money on a couple of trumpery hats as that!” he replied.

“Oh, dear!” Hero said conscience-stricken. “Ought I not to have done so? Only, one is the hat I wore when we drove out to Richmond, and you particularly commended it, Sherry!”

“No, no, there’s no harm done!” Sherry said, tweaking one of her ringlets. “Extravagant little puss! Wear it again today! I’ll drive you round the Park, if you care to go with me. I want to try the paces of that pair of chestnuts I bought at Tatt’s last week.”

“Yes, indeed I do!” Hero said, every cloud vanishing from her horizon.

Chapter Ten

IT WAS NOT, OF COURSE, TO BE EXPECTED THAT this was the only tiff which disturbed the peace of the house in Half Moon Street. A young lady, reared in the heart of Kent and uninstructed in the niceties of social etiquette, was to be depended on to make mistakes, and to get into all the minor scrapes which lurked in the path of any high-spirited damsel bent on cutting a dash in the world. The Viscount had been aware when he married his Hero that she knew nothing of the ways of the Polite World, but partly through a misplaced confidence in his mother’s willingness to take Hero under her wing and partly through an airy belief that Hero would soon learn the ropes, he had not anticipated that he would be required to play a large role in her debut. The fashionable ladies of his acquaintance were seldom dependent upon their husbands for their amusements, nor had they to be extricated from the consequences of ignorance. The Viscount had, in fact, plunged into matrimony with the lighthearted intention of squiring his wife to a few parties and assemblies, driving her out occasionally in the Park, and being pleasant to her over the breakfast cups. Such concessions as these to convention would scarcely interfere with the pursuit of his usual amusements. As for Hero, the Viscount was not an ill-natured or an unreasonable young man, and he meant to make no objection to her forming her own court, with its attendant cicisbeos, and even (if discreetly conducted) its amorous intrigues. He supposed that she would hold her card parties, and possibly fritter her pin-money away at silver-loo; buy herself her favourite number in the lotteries at Richardson’s; air all her most expensive toilets in the Park; and generally conduct herself like any other female of birth and fortune. It had never occurred to him that he would return from a shooting match at Epping to be met by the intelligence that her ladyship would not be at home to dine with him, as she had gone with a party of friends to Margate on the steamboat; nor that he would stroll into the Royal Saloon, in Piccadilly, in search of such amusement as this Turkish kiosk of a building offered, only to be brought up short by the spectacle of his wife partaking of supper in one of the booths, in company with a very fast young widow, and two of the wildest blades of his acquaintance. The fact that it was just such a party as he himself was in the habit of frequenting in no way mitigated his shocked wrath. The widow, with whom he was well acquainted, hailed him with arch good humour, and received for her pains a frosty glance, and the very stiffest of bows; the two young blades, recognizing from experience the unmistakable signs of an enraged spouse, suddenly became painstakingly discreet in their dealings with my Lady Sheringham; and only the erring wife herself remained unaffected by his lordship’s joining the party. This he did, and those who were used to look upon him as a regular out-and-outer who might be depended on to become the life and soul of a gathering of this order would have been hard put to it to recognize him in the punctilious young gentleman who took his seat at the rustic table, and proceeded to cast a damper over the evening. He removed Hero at the earliest possible moment, and lectured her all the way home on the impropriety of her appearing at such places, and in such company. She was at once contrite, but said that Mrs Chester, the smart widow, had claimed friendship with him, so that she had supposed that she must be unexceptionable. The Viscount was confounded by this, and ended the discussion by saying hastily that that was neither here nor there, and she was on no account to go to the Royal Saloon again. She promised that she would not, and the affair blew over. But a week later, the Viscount, having been made aware by the veriest accident of his wife’s fell intent, was only just in time to prevent her visiting a haunt known as the Peerless Pool. She was perfectly docile as soon as she was assured that no lady of quality would visit the Pool, and made so little lament at having her projected party of pleasure spoilt, that his lordship was touched, and voluntarily sacrificed his own plans to take his unsophisticated bride to Astley’s Amphitheatre, where they saw a spectacular piece entitled Make Way for Liberty, or The Flight of the Saracens. This was an unqualified success, and Sherry, who had thought himself above being pleased by such an artless entertainment, enjoyed himself amazingly, deriving even more amusement from Hero’s naïve wonder than from the marvels exhibited on the stage. At her request, he made a list for Hero of the fashionable places it would not be consonant with her dignity for her to be seen at. She conned it carefully, but it proved to be incomplete. The Viscount walked into his house early one afternoon to find a twisted note from his wife awaiting him on the table in the hall.

Dearest Sherry, [ran this missive] only fancy! Gussie Yarford, Lady Appleby, I mean, came to visit me, and she has a famous scheme for such a frolic! We are to go in our plainest gowns to Bartholomew Fair, and she says there can be not the least objection, for Wilfred Yarford and Sir Matthew Brockenhurst are to go along with us, so I know you will not mind if I am not back in time for dinner.

The Viscount let a strangled groan, and so far forgot himself as to clutch at his fair locks. His friend, Mr Ringwood, who had accompanied him to his home, regarded him with anxious solicitude.

“She’s gone off to Bartholomew Fair!” said Sherry, in despairing accents.

Mr Ringwood thought this over and shook his head. “Can’t do that, Sherry. Not the thing at all. Shouldn’t allow it.”

“How the deuce was I to guess such a notion would ever enter her head? Wild to a fault! Let me but get my hands on Gussie Yarford, that’s all! Gussie Yarford! The maddest romp in town! Why, not all her connections can get her a voucher for Almack’s, since she started to set the world by the ears! What I have ever done to deserve — However, it ain’t her fault: she’s no more notion of how to go on that — dash it, than a kitten!”

Mr Ringwood unravelled this painstakingly, and asked if he was to understand that Hero had gone to Bartholomew Fair with the notorious Lady Appleby?

“Yes, I tell you!” said Sherry impatiently. “Dare say she thinks it’s all right and tight, for you must know that the Yarfords live down in Kent. She has known Gussie any time these nine years — more’s the pity!”

Mr Ringwood looked very serious. “Very bad ton, Lady Appleby, Sherry. Appleby, too. Hope he hasn’t gone to the Fair with them. Can’t be trusted to keep the line at all.”

“Oh no!” said Sherry bitterly. “Not Appleby! Kitten knows I can have no objection to this expedition, because, if you please, they are taking Wilfred Yarford and Brockenhurst along with them!”

Mr Ringwood’s jaw dropped, for he had some acquaintance with Lady Appleby’s enterprising brother Wilfred, and still more with Sir Matthew Brockenhurst. After a stunned moment, he said with great earnestness: “Sherry, dear old boy! No wish to put you in a pucker, but that fellow Yarford — no, really, Sherry, he’s a devilish ugly customer!”

“Lord, don’t I know it?” Sherry retorted. “And as for Brockenhurst — Dash it, I suppose I ought never to have had him to dine here! Ten to one Kitten thinks all’s right because of it! Well, there’s only one thing for it: I must go after them! I’m curst sorry, Gill, but you’ll have to find someone to take my place in our little jaunt. Try Ferdy! You see how it is: can’t help myself!”

“But, Sherry!” protested Mr Ringwood. “Can’t have considered! Won’t find ’em! Not in that vast rout!”

“Well, I can make a devilish good attempt, can’t I?” retorted Sherry. He added with some shrewdness: “If I know anything of Kitten, she’ll be sitting in Richardson’s Great Booth, watching some shocking bad play, or staring her eyes out at a Learned Pig, or some such stuff!”

Upon reflection, Mr Ringwood was forced to own that this was very likely. Perceiving the frown on his friend’s face, he gave a cough, and ventured to say: “Y’know, dear old boy — not my business — but she don’t mean an ounce of harm! Only saying to George last night: dear little soul! Not up to snuff at all!”

“No, my God!” agreed the Viscount feelingly.

“Tell you what, Sherry: if I had a wife, which I’m deuced glad I haven’t, I’d rather have one like your Kitten than all the Incomparables put together.”

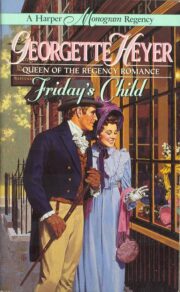

"Friday’s Child" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Friday’s Child". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Friday’s Child" друзьям в соцсетях.